Back to selection

Back to selection

TIFF 2015 Critic’s Notebook #3: Guy Maddin and Alan Zweig Offer New Notions of Being Canadian

Bring Me the Head of Tim Horton

Bring Me the Head of Tim Horton Growing up, no two things did more to define Canadianness than Tim Horton’s commercials, with their warm and fuzzy scenes of dads bringing hot chocolate to the hockey rink, and Heritage Minutes, vignettes reenacting “proud” moments ranging from Native Americans teaching early settlers how to make maple syrup to the moment Marshall McLuhan came up with the phrase “the medium is the message.” Too often Canadian film seems aimed at riling up the same hollowed-out brand of patriotism. The cause of this is at least partly due to the fact that its funding is frequently tied up in a government-sponsored cultural-identity building project. Two works at TIFF, however, comment on this project rather than merely reproducing it: Bring Me the Head of Tim Horton, a 30-minute looping video installation by Guy Maddin, Evan Johnson, and Galen Johnson; and Hurt, a documentary by Alan Zweig.

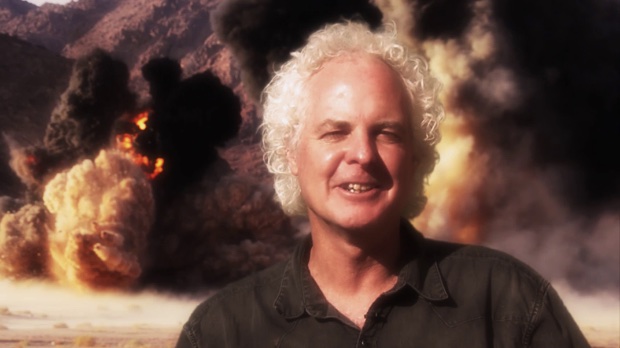

There’s a Tim Horton’s coffee shop directly across the street from the Bell Lightbox, the festival headquarters, where Bring Me the Head of Tim Horton is playing all week on repeat. The film is ostensibly a behind-the-scenes documentary about the making of Paul Gross’s Hyena Road, a Canadian Afghanistan War movie in competition at the festival, but of course, because Maddin’s at the helm, it’s much weirder than that. It knits together green-screen, Guy LaFleur’s disco, drones, ironic promo, and shots of Maddin lying around in the desert pontificating about war movies.

Early in the film, Maddin establishes himself as the antithesis of Gross, whom he calls “a great Canadian populist.” Gross is thoroughly famous in Canada. Few outside the country have probably heard of the two things the actor, writer and director is best-known for — a TV show about a mountie, Due South, and a movie about curling, Men with Brooms — but everyone and their uncle in Canada knows him. He’s had a career working in the kind of Canadian content you’re overwhelmed with growing up, content that the government ensures makes up a certain percentage of your media diet and that today I feel both alienated from and nostalgic for. It’s this mixed feeling Maddin gets at.

Maddin wryly explains he was running out of money working on his own feature and thought he could make some money shooting this behind-the-scenes doc. He compares his own budgets with Gross’s. He’s tongue-in-cheek as he lays out the contrasts, cardboard sets versus an entire village constructed in the Middle East in Jordan. Still, there’s an implicit critique in what the country is choosing to film.

When watching anything Maddin makes, there’s always the feeling that no one else in the world could have made this. In addition to Bring Me the Head of Tim Horton, he has a feature at TIFF, Forbidden Room, which structures itself like those Russian nesting dolls, one absurd story within another. A submarine crew doomed with limited oxygen gorges on pancakes with air pockets baked into the batter. A man in a bathrobe talks about the rituals of bathing. A widow makes her young son wear the moustache of her dead husband. These stories and others are told in the style of a psychedelic reimagining of silent film era movies, using both sound and title cards. The result is something delightful.

Maddin is the kind of artist Canada should be really proud of. But we are so thirsty to be proud of things, to exist outside of America’s shadow, and we have all these quotas mandated to do so, it’s almost as if there’s a desperate nervous energy to it all sometimes. Alan Zweig’s documentary Hurt profiles Steve Fonyo, a man who is in many ways a casualty of this hyperactive urge for something patriotic.

Fonyo is the less-famous of two Canadian amputees who separately embarked on cross-country runs to raise money for cancer. Terry Fox was the first to do in 1980, but he never finished. Cancer spread through his body. Soon after he had to quit the run, he died. Few have the hero status that Fox has in Canada. In fact, they just released a new Heritage Minute about him this month. A few years after Fox attempted his run, Fonyo embarked on a similar journey and successfully completed it. He was celebrated too. There was a beach named after him. He was on talk shows and part of football halftime shows. But then he got into some problems with drugs. He was caught forging checks. Eventually, the government took away the Order of Canada prize they had bestowed on him.

The documentary focuses on Fonyo today. He’s living in Surrey, a city plagued by poverty and addiction not far from Vancouver, B.C. Toothless grins are common. So are bad meth habits. Fonyo would be an entertaining enough character even without the missing leg and the fallen hero backstory. He’s unflinchingly honest even when he’s lying. A love triangle develops when Fonyo leaves his wife Lisa for a new girlfriend Lisamarie. There’s no lack of drama after that: Lisa presses charges against Fonyo for assault, and the neighbors start stealing things from Fonyo and Lisamarie.

Zweig, though, ensures the doc is more than just white-trash reality TV. Firstly, because of the palpable respect he has for the characters on-camera. But also because he weaves in footage of Fonyo from the height of his 15 minutes of fame, full of patriotic pomp and ceremony. Zweig does it in a way that suggests lionizing people sometimes has consequences. He asks, do our heroes owe us something or do we actually owe them? And while Fonyo’s celebrity is particularly Canadian, as the internet fuels micro-celebrity culture, the film’s commentary on an addiction to fame transcends the specific national context.