Back to selection

Back to selection

TIFF 2015 Critic’s Notebook #5: An Old Dog’s Diary, Cemetery of Splendour and Chevalier

An Old Dog's Diary

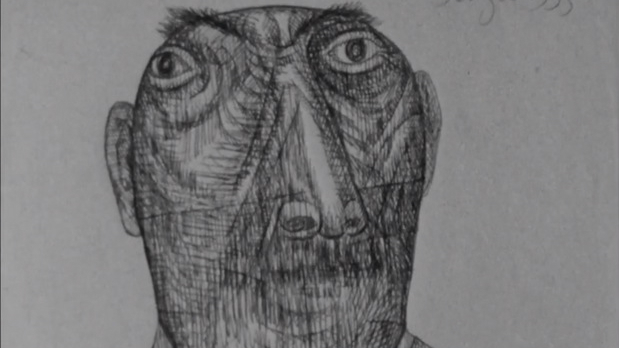

An Old Dog's Diary Ghostly echoes fill An Old Dog’s Diary (2015), a highlight of the Wavelengths experimental short programs at the 2015 Toronto International Film Festival. This impressionistic, documentary portrait takes as its subject F. N. Souza (1924-2002), a man anointed by The Guardian “India’s most important and most famous modern artist.” Made by Shumona Goel and Shai Heredia, each an accomplished artist in her own right (Heredia is also the founder of Experimenta, a leading Indian experimental film society), the evocative 11-minute film takes a sidelong approach to cinematic portraiture. Textural glimpses of Goa, Souza’s birthplace, are casually depicted on black-and-white Super 8 and 16mm film: the shimmer of the water in a verdant bayou; children squinting in the sun; the play of light through a lace curtain. The film’s otherworldly sonic environment is interrupted only for a single lilting, crackling pop song. (Heredia identified this song for me as “‘Molbailo Dou,’ from the famous Konkani film Amchen Noxib, made in Goa,” information that inspired a research spiral that I imagine FM’s readers will similarly enjoy). Meanwhile, lines of Souza’s own writing appears across the bottom of the frame like subtitles for words that are never spoken aloud. Souza is a subject ripe for documentary; in addition to tales of a colorful personal life and darkly vivid canvases, he left behind a literary corpus that includes the illustrated book Words & Lines (home to his memorably-title auto-biographical essay, “Nirvana of a Maggot”). Coincidentally, just days ago, Souza’s painting “Birth” was sold by Christies for over $4 million, a new record for the most expensive work ever sold at a South Asian art auction. Though perhaps best known for oil paintings like that one, it was Souza’s line drawings upon which Goel and Heredia’s camera rested — including these Six Gentlemen of Our Times — that stayed with me longest after this tiny gem of a film had ended.

The spirit world comes similarly alive in Cemetery of Splendour, the mesmerizing new feature by Thai director Apichatpong Weerasethakul. Like a fairy tale princess in a fable of yore, a soldier (Banlop Lomnoi) sleeps in a breezy country hospital ward in northern Thailand, seemingly never to awake. A cadre of similarly afflicted fellow soldiers fill the ward berths around him. Curious Jen (Jenjira Pongpas) visits the soldier day after day, caring for and wondering about him in equal measure. What is this mysterious “tropical malady” from which he suffers? Are there ancient roots to the affliction? What will he say if a young psychic channels his thoughts? Can his dreams be made more peaceful with the latest technology, an innovation involving glowing lights and developed by Americans? Beloved by international audiences for the Cannes-winning film Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives (2010) as well as previous TIFF favorites like Syndromes and a Century (2006) and, of course, Tropical Malady (2004), Cemetery of Spendour was here aptly positioned in the Masters section, while an installation of the same director’s Fireworks (Archives) (2014) was presented as part of the Wavelengths slate. Myth and dream come together in Cemetery of Splendour as beautifully here as in the director’s previous works; this time I was reminded of Don Delillo’s White Noise by the film’s gentle ironies, the ease between its characters and the seamless shifting of past and future, buoyed by subtle political undercurrents.

The physical realm is what counts in Athina Rachel Tsangari‘s Chevalier (2015), where a sleek yacht upholstered in cream leather is the setting for a not-so-friendly competition between Greek gentlemen of leisure. Who is the most handsome, virtuous and cool, the all-around best specimen of manhood? Whether comparing and rating each other’s diving skills, romantic relationships, Ikea-furniture building skills or (gulp) erections, each man — from studly Christos to schlubby Dimitris — will stop at nothing to win the chevalier pinky ring as a signal of his dominance. Ostensibly a gender send-up spoofing those of the male persuasion, the film can also be read as political commentary (see: Greece, economy) or critique of vain, self-involved, selfie-prone humanity writ large. Onscreen one-upmanship has long proven to be fertile narrative ground and here it’s satisfyingly explored by Tsangari, known to festivals audiences for her wonderful portrait of female friendship in Attenberg (2010). The spectacle of competition is as popular as ever before, lately finding audiences in television shows from The Voice to The Bachelor as well as movies like The Hunger Games (2012) and its bloody predecessor, Battle Royale (2000). Indeed, Chevalier‘s elegant plot is so ripe for Hollywood adaption that it’s also easy to picture a big-budget version coming soon to multiplex or streaming platform near you. Stephen Colbert, Ben Stiller or Joe Mangianello could find comic gold in the premise while new shades of meaning could be found in an all-female version that could be led by Tina Fey, Julia Louis Dreyfus and Jennifer Aniston. One only hopes that future iterations retain Tsangari’s deadpan humor, adventurous soundtrack and the haunting cinematography that turns the slate blue of the Aegean Sea the biggest winner of all.

After that, all bets are off.