Back to selection

Back to selection

Danger Man: Josh Kriegman and Elyse Steinberg on Weiner

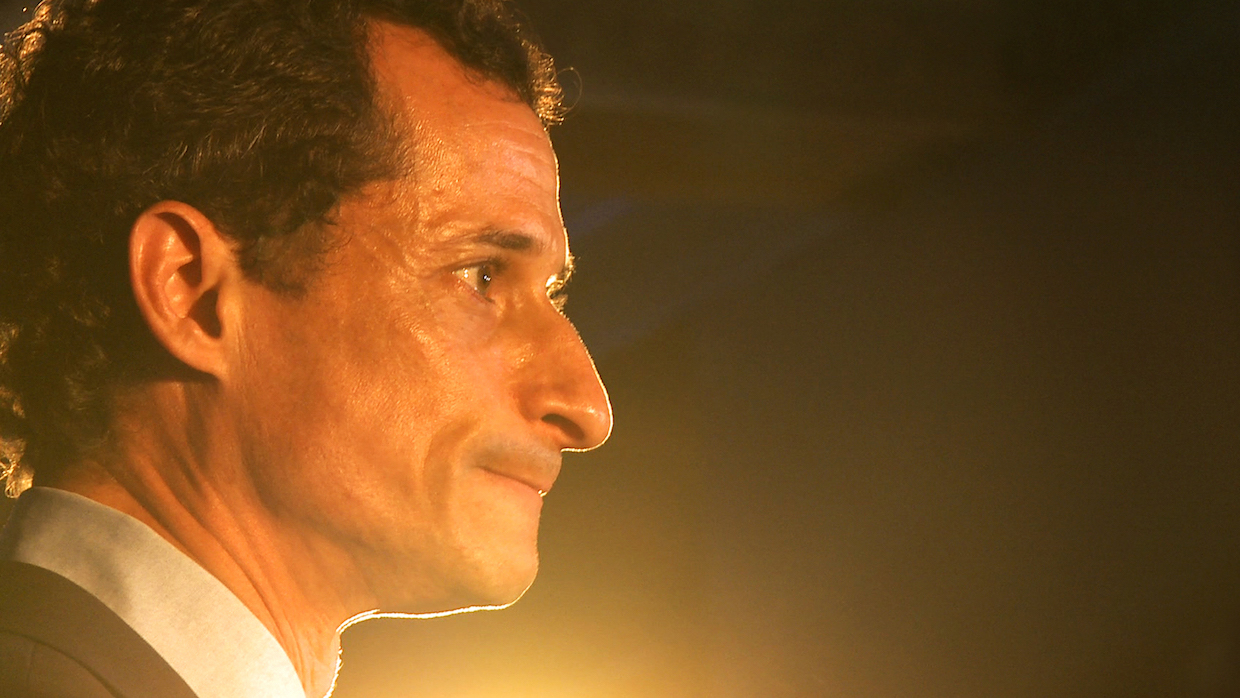

Anthony Weiner in Weiner (Photo courtesy of Sundance Selects)

Anthony Weiner in Weiner (Photo courtesy of Sundance Selects) From where we currently sit in the middle of the Great Reality Show Presidential Primary Race of 2016, it seems like a point so obvious as to be nearly mundane: Politics can be the greatest show on earth. And, since the birth of the technology, that show has played out in front of the camera.

Picking apart the symbiotic relationship between the media and politicians is an old conversation, merely updated with an ever-evolving set of tools: From Andrew Jackson, who controlled at least one newspaper and also blamed the press for ruining his wife’s good name, to Gary Hart, who, when faced with rumors of sexual impropriety, infamously dared the media to follow him around (which they did), the same questions have always applied to the Fourth Estate: who’s gaming who? Is politics the highest or the lowest calling? What is sensationalism, and what is news? What do we want out of our politicians — and what do they want out of it?

Into that fertile conceptual ground steps yet another camera — that of Josh Kriegman and Elyse Steinberg, co-directors of the rollicking, high-octane Weiner, the Documentary Grand Jury Prize winner at this year’s Sundance Film Festival. The film follows the rise and fall of the eponymous Anthony Weiner over the course of his New York City mayoral run in 2013, from high hopes that he’ll be able to stage a political comeback, to the shockwaves that follow when yet another sexting scandal erupts, to Weiner’s determined soldiering on to finish out the campaign amidst the overwhelming media turmoil. Weiner is constructed from a mix of on-the-ground vérité material shadowing Weiner and his wife, Hillary Clinton aide Huma Abedin, in the office, on the trail and in their home, as well as archival news coverage and graphic treatments taking a page from the House of Cards book (how exactly do you image a sex scandal that plays out over text message?).

Kriegman once served as an aide to the then-Congressman, and the directors are given shocking access. “Why are you letting me film this?” Kriegman asks incredulously at one point, a question that’s never quite answered and forms to my mind one of the more beguiling knots in the film: What does it mean to be another camera-amongst-cameras in a film that’s documenting the role of the camera in politics?

Were you both shooting for this documentary, or was it just Josh? Kriegman: Most of the shooting was just me. Elyse and I had been working together for a couple of years before we started working on the Weiner film. At first, we tried to have a cinematographer with me, but very quickly it became clear that there wasn’t room for more than just myself. So, I ended up picking up the camera and, I would say, most of the filmmaking is just me. There were a few points where Elyse came in or there was another second shooter that we brought in — on Election Day or other important moments throughout.

Josh, you being the main shooter — was that just because there wasn’t enough room, or would Anthony also change when you had another person there? Kriegman: It was both. There just wasn’t space for another person. But it did help with the rapport and the intimacy, definitely. I was riding in the car and was really by his side through most of the twists and turns of the campaign. He and I had known each other for a long time, and that was part of the dynamic of shooting, just me being there with him.

Steinberg: Josh and I were talking throughout and discussing story and figuring out what we wanted to do. We had other shoots. Sometimes we were filming other candidates, and we were also filming at big events — election night, the debates.

I was so curious about how you divided labor, particularly because I know that you were involved with Anthony in the campaign, Josh. Elyse, what kind of balance did you provide? Steinberg: In terms of the workflow, Josh was there on the ground. Then, when the filming was done, we both were looking through the material. We had 400 hours. I’d been making documentaries for PBS and A&E, and I was really excited about making this character-driven, vérité documentary. I’m much more like a viewer; all I knew about Anthony is what you saw in the headlines. So, I think I brought that kind of perspective to what was happening.

Kriegman: But yeah, we were fully co-directing the entire time.

I’ve co-directed before, and what I’ve always found to be so helpful, but also so difficult, is having two different perspectives in the edit room. Was it valuable to have someone on the outside, who didn’t have the same sense memory of being on the shoot, to provide balance during editing? Kriegman: It became very clear through the process that certain kinds of distance were really helpful. Elyse wasn’t in there all day every day in the same way that I was, although we were talking nonstop. And then, of course, our editor [Eli B. Despres] had another kind of distance. He just approached the footage totally fresh, having obviously never met Anthony, and he had very little exposure to anything beyond just what was in the footage.

Steinberg: [Josh and I] have different ideas. We approach it differently. We are different people. But then, we’re able to really collaborate together and listen to each other. We and our editor, who has got a totally different personality, came together in a mutual sort of respect. Maybe it’s from a gender place also, but I do think that I could identify with Huma a little bit. I think Anthony initially was harder for me to get.

Let’s talk about Huma. I had such a physical, visceral reaction to a lot of the film. And part of that had nothing to do with politics; it was just more on a human level. Anyone who’s ever been in a relationship, a partnership, must react to having complex private dynamics exposed to the world and picked apart…It was really hard for me to watch. Kriegman: Their relationship, prior to the film, had already been picked apart and judged and ridiculed. And in a lot of ways reduced, right? There’s tons of ridicule and judgment heaped on Huma for the choices that she made through it all. There was this impulse to judge their relationship in, I think, a very simplistic way. People have this urge to just decide, to make a judgment one way or the other. And I think part of what we hope is exciting about our film is that we get a chance to take a closer look, and in some ways, to also take a step back from the easy narratives. In terms of their relationship, they do have a normal relationship. It’s not something you need to judge.

Another thing my directing partner, Jamila Wignot, and I came up against in our documentary, Town Hall: making a long-term film that you know is a long-term film, but also living in the minute-by-minute news cycle as events are happening. Having one foot in both worlds can create a very disorienting perspective. Did you find this the case as well? Kriegman: It was fascinating to sort of have both angles of it; taking the headline version or the cable news sound bite, and then flipping it and getting the chance to look behind.

Steinberg: We knew immediately that we wanted to show you the headlines, show you the way in which some of the characters were criticized, ridiculed and then show them as human beings. The Lawrence O’Donnell interview [in which Weiner is interviewed by the MSNBC host while sitting alone in a separate studio] is emblematic. We played with that — you just see that one screen, and then you get to see that side angle in an empty room. That aesthetic side angle, it speaks volumes.

There’s something that kept reoccurring in the film, the idea of the performance of politics. You have all these different levels of performance: Anthony recording ads, the debate, the press conferences. Did you two discuss the idea of politician as performer? Kriegman: It’s such a central idea of the film. Not only is [the film] about Anthony, the campaign and this one moment in political history in New York, it’s also about, sort of, what our politics has become. So much of it is theater — spectacle overtaking basic substance.

What about your own roles in this film — your presence behind the camera? Did you feel it was important in the movie to draw attention to yourselves? Steinberg: I think it was important to acknowledge our presence, and we did that throughout in little ways. We didn’t want Josh to become the story, because it really is Anthony’s story. But we bookend the film with Anthony talking about the documentary [and why he let us film]. So I think it was important for that to be a part of the story, to acknowledge our presence there, our truthful representation, and to play with this.

Kriegman: The media is a character in the film. But obviously, we can’t escape the fact that we also in some ways are part of the media ourselves, right? Bookending the film with [his dialogue] — “I hope this documentary is not a punchline. So, will it be?” I think that that was our way of talking about the filmmaking process, our own self-awareness.

Did you wrestle with that? Steinberg: Yes, a little. I think we understood it. We thought about our presence, and that’s why we film ourselves [discussing] that.

Kriegman: I don’t know if it was a struggle, so much as it was important for us to acknowledge it. Throughout the course of making the film there were many more [moments] when [Weiner] was aware of the documentary filmmaking process. He was constantly commenting to me about it.

There’s that moment when Anthony says to you, Josh, “I thought this was ‘fly-on-the-wall.’ I never heard a fly on the wall talk as much as you.” Steinberg: That joke, for documentary filmmakers, is pure gold.

Kriegman: [Weiner’s] relationship with the media and with the camera is very complicated. He had, at that point, been in public life for, I think, a little over 20 years. It was something that he was comfortable with and used to. And [this] speaks also to the reality of what it is to be a politician, how that becomes engrained in your daily life and in your psyche. You’re in that [public-facing] mode all the time.

Weiner’s perception of what the film would be — do you think it changed over time? Kriegman: I don’t know. We posed this question to him in the film. It’s obviously the question that we had throughout: “Why did you let me film this?” I think [he hoped the film] could be a more real or human or nuanced or complex version of his story than the one that played out in the headlines of The New York Post. I think that’s part of why he wanted the film made, and I think that remained true throughout. When the scandal resurfaced and threatened and ultimately did overshadow everything else, in some ways, that motivation became more pronounced.

Right, like, “Now I really need this film.” Steinberg: Yeah. The events changed, and obviously, the sexting scandal broke and our story changed, but our intention stayed the same throughout the making of the film, which was: here was a person who was reduced to a character, and let’s show a more complex reality.

Kriegman: But of course, in the first six weeks or so, it looked like he was doing very well, right? He was winning. He was at the top of the polls very quickly, he was really defying expectations, and from the filmmaking perspective, we thought, “Wow, this could be an amazing, unprecedented comeback story.” And then, of course, it changed, and we kept filming.

Were there moments in there that he wavered on allowing you access? Kriegman: Definitely. There’s a moment in the film where he asks us to leave the room right as the scandal resurfaced. There are definitely times when he asked for privacy, and we obviously respected that. But for the most part, we were pretty much there through it all.

Four-hundred hours has become a normal amount of footage for a doc, but I know for The War Room, they shot only 35 hours, which is incredible to think about. What was your process of sifting through all of your footage? Did you have a sense of the clear arc? Between you and your editor, how did you shape it? Kriegman: We were fortunate to have a narrative arc as the backbone of the story, which isn’t always the case. We had this election, and we had the course of the scandal and how that unfolded.

Steinberg: And we had our co-producer Liz [Delaune Warren]. We had other people who helped us look through the footage, logging it. But we sat with that footage for like a year.

Kriegman: If you’re filming all day every day, there’s a lot of hours of not necessarily a whole lot happening!

Would you keep filming, or would you turn the camera off and just hang out? Kriegman: Well, basically, I was trying to film everything. I mean, this is one of the challenges, I think, of vérité filming like this. You have to keep the camera rolling if you want to be sure to capture things when they happen, right? And then, of course, you pay for it.

Steinberg: In the end.

You pay for it on either side — if you turn it off… Kriegman: There was a point where I mentioned to Anthony, “Yeah, I’m going to have to watch all this footage.” And he was like, “Oh god, I don’t envy you.” [Laughs]

Did you find the process of making this film different than the other films you’ve made? Steinberg: I did a documentary of the trial of Saddam Hussein, and it was similar, in that it was about this one moment, this single trial. Trials and elections have a natural arc, so that was similar. But for that we did interviews, and it was teasing out an idea, so that was very different.

That election night scene [in which one of Weiner’s sexting partners shows up outside his headquarters] is just so insane. Sydney Leathers shows up, and your camera chases Anthony through the kitchen as he tries to avoid her. It’s like out of a genre film, a thriller. Obviously you guys knew that election night would be some sort of climax, even not knowing exactly what would happen. How did you prepare for that shoot? Kriegman: It actually wasn’t that complicated, really. I had obviously been following alongside Anthony the whole time. Since it was Election Day, it was obviously an important moment that was definitely going to be in the film. And so we brought on another cameraperson. Then, through the course of the day, Sydney Leathers emerged, so we knew to stay with her. It was really that simple. We had one person on her, and myself with Anthony.

Steinberg: We actually had three cameras on that day.

Kriegman: Yeah, we had an associate producer also for a little bit more coverage.

I think about documentary ethics all the time. The responsibility to a person who’s entrusted you with access, and the responsibility to making something truthful, but also the reality that this is your own specific interpretation. How did you think through those questions? Kriegman: It was really important to us, obviously, to be telling a true story, and to be totally fair to Anthony and to the narrative and to the event — to be as honest as is possible. It is hard. This was obviously, at times, a very painful experience for him, and it [wasn’t] something he was eager to relive. But as we said before, this idea of trying to get at the reality of what it all looks and feels like in contrast to the sort of tabloid narrative in the media, that was our kind of guiding compass.

Steinberg: One thing that’s exciting about documentaries is you get to spend 90 minutes with a person. I spent three years thinking through this [film]. You asked why we wanted [to make] a character-driven vérité documentary. It’s just like you’re sitting with that experience. We’re not telling you a point of view here. That was one of the things we wanted — not to give you a point of view. To show you and raise questions.

At the very end, Anthony says something like, “The laws of entertainment will suck your documentary into the vortex of the scandal.” That’s such an amazing sentiment—it sums up the whole film, in a way. Do you feel like that has, in fact, played out? Kriegman: Some of it remains to be seen. I mean, the film will come out in the end of May in theaters. We’ll get a sense of how people react. We hope that people are able to recognize and appreciate the full picture, the complexity of the nuance that we tried to construct and to tell, [and that it’s a] reflection of the reality as we saw it.