Back to selection

Back to selection

“Why Don’t We Just Make it Seven-and-a-Half Hours?” Director Ezra Edelman on O.J.: Made in America

O.J.: Made in America

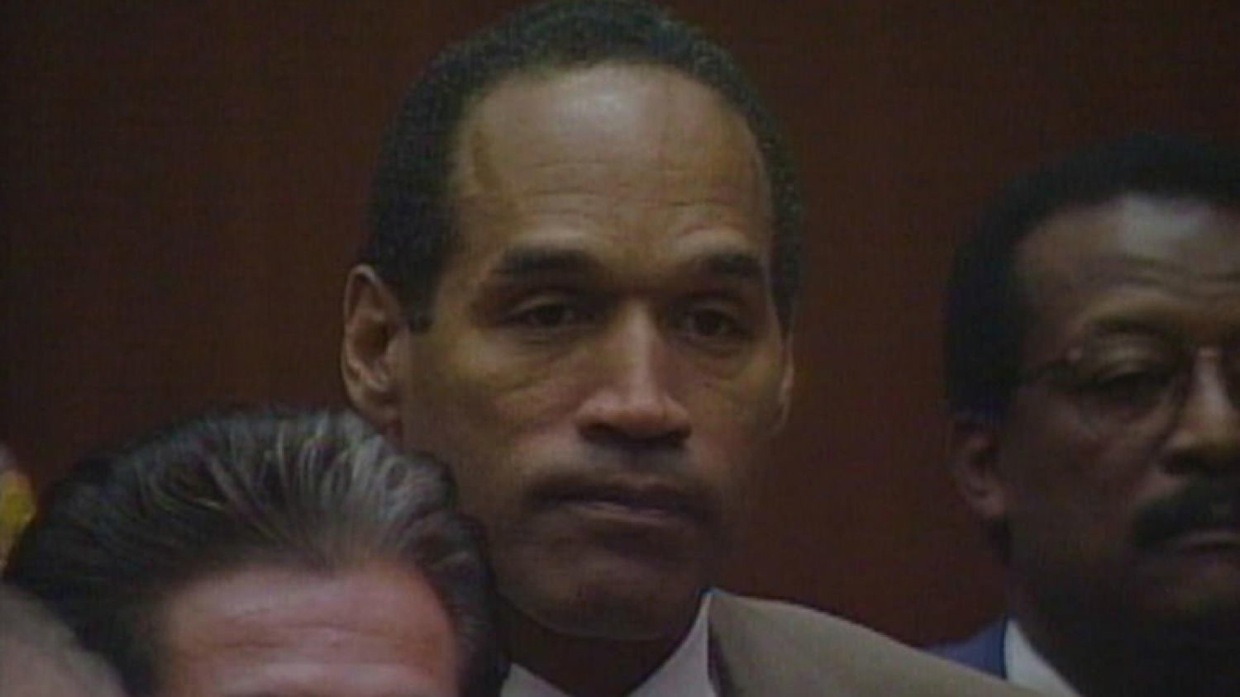

O.J.: Made in America How could close to 150 million people watch with rapt attention the exact same televised trial and come away with such passionately different responses to the verdict? Ezra Edelman’s epic, important and masterful documentary, O.J.: Made in America, spends close to eight hours exploring why you might have felt very differently from your neighbor. And, despite its length, nothing included is filler.

OJ: Made in America, will air on ABC and ESPN beginning June 11th. I sat down with Edelman — a producer and director whose previous works includes sports documentaries for HBO and ESPN’s “30 for 30” series — to discuss his take on some of the O.J. case’s major players, watching The Jinx midway through production, and his decision to go long.

Filmmaker: I understand that it may not be practical, but I wish that everybody would watch this as a seven-and-a-half-hour movie.

Edelman: So do I. Tribeca was the first time where [it screened all the way through with an intermission], and when people were together, the atmosphere in the theater and the dialogue that happened for that half-hour intermission — it was great. And I realized that this is sustainable. I mean, I think you have to get sort of amped.

Filmmaker: It does feel like it’s structured as one film.

Edelman: Yes, it is. Connor Schell, who’s the EVP of ESPN Films, came to me and said, “We want to start doing more ambitious projects. We’re interested in doing a five-hour movie.” And I was like, “Oh, I’m interested in that.” I was just interested in something formally more ambitious. I set out to tell one big story. That ended up getting bigger.

Filmmaker: It got bigger than its original five hours.

Edelman: At a certain point, three months into the editing, I was like, “Yeah, this needs to be five real hours, not five hours of television. And Connor said, “Cool.” A month later I was like, “I think this needs to be six hours.” And he was a little like, “Okay, so we’re talking about 330 to 360 [minutes]?” “I don’t know — yeah.” I had an 11-hour cut, so that was my mission for the summer, to get it down to six hours. By the time we actually had to show a rough cut, it was a little over seven-and-a-half. We had a screening, and I was super nervous. I didn’t know how they would react. At the end he was like, “Yeah, why don’t we just make it seven-and-a-half hours?”

Filmmaker: You were working with an enormous amount of archival footage.

Edelman: As you know, the first thing you do is hire really good people. [Producer] Caroline Waterlow, who I have been friends with and known for a while, found [producers] Tamara Rosenberg and Nina Krstic. I actually am amazed and wowed, because it’s sort of like this thankless task: go find everything. There’s accessing the LAPD archives and getting stuff from them, and you don’t know how cooperative they’re going to be. We got a treasure trove of archival material from [journalist] Larry Schiller, who was embedded with the defense during the trial. He had things that I didn’t even know existed, a lot of personal things that we wouldn’t have otherwise had access to. Honestly, I’m used to watching every piece of archival material that comes in, because that also informs further decisions. This was the first time when I was too under water with just trying to tell the story and trying to get this narrative straight. Between Nina and Tamara and Caroline, and also our three editors [Bret Granato, Maya Mumma, Ben Sozanski] — ultimately, there was a trust at a certain point that I couldn’t look at everything. Those guys are really good at what they do. When it comes to ceding control, it then has to do with trust.

Filmmaker: You can feel it when you meet the right people to work with.

Edelman: Yes. I had met Ben before about something else, and I was like, “Oh yeah, you’re the one.” The whole film is about who we are and what we bring to these stories and how we look at them.

Filmmaker: Do you know how much footage you were cutting down from?

Edelman: I honestly have no idea. I would say the amount of footage that we amassed was off the charts.

Filmmaker: There are some films that I’m curious if you watched —

Edelman: Shoah?

Filmmaker: Yes, Shoah. Ha. No, the two Anita Hill films, Concussion …

Edelman: I haven’t seen them. With this [film] for some reason, I went out of my way not to watch things. I didn’t watch anything, and then at some point during the process, The Jinx comes out, right? What was interesting to me about that was I watched the first episode. I was curious about how it was executed formally, in terms of technique, and I was kind of depressed. And I liked The Jinx. When you watch the first episode, formally, it does everything: beautifully shot reenactments, more traditional location things, taking characters out into the world. There are five different techniques, and it’s done in a way that for me, I was like, “I can’t do all that shit.” Whether it’s good or bad, or right or wrong, I’m like, “I don’t have the time, money and maybe even the know how, so I’m turning that off.” I didn’t revisit The Jinx for a while because then the next thing I read about it was, “Robert Durst confesses,” and I’m like, “Oh, great, so now I’m making a doc about someone who everyone believes committed murder – and guess what I’m not going to have someone at the end saying, ‘I did it.’”

Filmmaker: Which is one of the things I appreciate about your film, though.

Edelman: I mean, it’s obviously a different mission.

Filmmaker: The ones that I brought up are also completely different. I was trying to move into this idea that the film is not really about O.J. Simpson. I was thinking about other films that tell a story of how America is divided in their reactions to these public cases. Obviously the O.J. case was hugely divisive.

Edelman: Right. I wouldn’t have committed to doing it unless there was knowledge that there was a greater canvas, [one] that didn’t have to focus on that thing that I knew had been talked about over and over again. I’m not examining the murder. How am I letting certain segments of the population understand what happened on October 3rd 1995? I’m going to give the audience a primer historically so they might be able to empathize in a way that, frankly, I’ve been confused that they never have been able to empathize before. Like, it’s not confusing to me —

Filmmaker: It’s not confusing to me either.

Edelman: Why are some people so shocked by that? And why are they so upset? And yes, I’m talking about white people.

Filmmaker: I know.

Edelman: I don’t want to sound so naïve, but it’s weird to me because the historical context and the weight of that history and what African Americans have lived through in our country, and specifically in L.A., it’s so obvious. I also find that there is a tremendous sadness, let alone irony, in that reaction to something having to do with O.J. And that also was the story: this is how fucked up this whole thing is. I’m sort of speaking to two different audiences in terms of what I’m actually trying to convey.

Filmmaker: Not an easy thing to do. I don’t know why [white] people didn’t already understand, but they sure didn’t.

Edelman: I’m even amazed now with people’s reactions to the movie. They’re often like, “I didn’t know that. I never understood.”

Filmmaker: What else are people coming to you and saying?

Edelman: A lot of that. I’ve been using this phrase which someone said last week, and I just appropriated it: collective amnesia. I think, especially now, we are so — it’s about us. Me. The present. History is just something that’s lost. They go, “I didn’t get it. Now I get it.” So, what’s interesting to me is, well, then good, we did our job. But why didn’t you get it?

Filmmaker: Right. Because it’s getable.

Edelman: It’s getable. And by the way, I agree with people who say, “That’s fucked up, people are celebrating….” But I’m like, “Just get your brain out of that space. They are not celebrating a murderer going free.” I get it, but if they want to understand, you can’t put yourself into another person’s skin to understand just what the series of injustices they live with every day. You need an outlet and unfortunately, if that’s the outlet, yes, that’s fucked up.

Filmmaker: So many fucked-up things in the world.

Edelman: That’s true.

Filmmaker: You had two jury members on camera.

Edelman: We tried to track down all of them. Some people we just didn’t find. This was all Tamara Rosenberg’s [work]. We had a meeting with another juror, another black woman on the jury. She was very nice. No one wants to talk. Even those two — I mean it was a very important thing [to find jurors who would be on camera]. Carrie [Bess], the older woman, we had coffee with in L.A.. She lives in South Central. She was very nice. She initially said yes, but then didn’t really follow through. We’d go out there probably every month for four months to do another round of interviews. Tamara would go visit and just hang out with her, and at a certain point they became friends and she was like, “I’ll do it for you.” Yolanda [Crawford] who was the younger one, Tamara found her. We had lunch. We talked, we had a good conversation, and she said, “Cool” At the end of the lunch, we said, “Alright, Yolanda, would you be willing to sit down for an on-camera interview?” She was like, “Oh, no I’m not going to do that. I don’t want to do that.” And then she said, “I’m fucking with you!”

Filmmaker: Really? That’s funny. She has a sense of humor.

Edelman: She was great. The reductiveness that we have in our culture about why this happened — here are two black women with completely different brains who looked at what was happening in completely different ways. It was very important, I think, for people to see that.

Filmmaker: Some of the more familiar people in the film are Marcia Clark and Mark Fuhrman. I’m never surprised that people will talk, but I was certainly interested that Fuhrman talked. How did you approach him and what was that experience like?

Edelman: To your point, it’s hard to understand people’s motivations. But you are also dealing with people who get calls incessantly and have for 20 years. How do you get past a wall to have them listen? We told him, “We are doing this. It is much greater in terms of scope than any thing, it’s not solely about the trial. We are pretty thoughtful about how we are going about this. Just so you know, it will be seen widely. You will be in this movie…”

Filmmaker: “…Do you want to be in it telling your version?”

Edelman: That’s sort of the approach: let’s sit down, have a conversation, in a good way. I think to a man or woman, every interview we did, afterwards they said, “Okay, that was better than I thought.” Once you got past that initial [suspicion] and you started engaging, I think it made them feel more comfortable: “Oh, okay, this is different.” I didn’t sit down with Mark Fuhrman to determine whether he was a racist. But those two people [Clark and Fuhrman], outside of the jurors, they were the two most difficult people.

Filmmaker: The most difficult to get, or the most difficult to talk to?

Edelman: Get. Fuhrman was difficult to talk to. Marcia, once she decided to do it, she was great. Marcia brought it.

Filmmaker: She was very interesting to listen to.

Edelman: The other thing about this, and this gets to the notion of what is truth — you sit down with people and they all have their [stories], and I don’t know that they are wrong. Everyone has their own personal truth.

Filmmaker: Was there anybody who really surprised you, who was different from what you were expecting?

Edelman: No. I mean, Fuhrman surprised me a little bit.

Filmmaker: In what ways?

Edelman: He was very smart. There was a lot more of a calm, subdued presence to him than I expected. I don’t know what I expected.

Filmmaker: Were there people you wanted who said no?

Edelman: [Prosecuting attorney Christopher] Darden.

Filmmaker: He just flat out said no?

Edelman: He flat out said nothing for a long time, and then he finally said no. The hardest person in some ways to get was Garcetti [former DA, Gil Garcetti]. That took a few conversations. Once he said yes, then we could go to Bill Hodgeman [prosecutor], who had been like, “Maybe I’ll have an off-the-record phone conversation with you, but I don’t really want to deal with this.” And then, “Okay, I’ll meet with you.” I think that all sort of moved the ball forward in a good way. With Darden it didn’t really help. There are certainly people in O.J.’s inner circle that I would have loved to interview. Frankly, I was more realistic about those chances. I didn’t go into this thinking that I was going to be the person to get Al Cowlings to sit in a chair. Or Marguerite [Simpson’s first wife, Marguerite L. Whitley]. I would have loved to have interviewed Marguerite more than any one else. Probably more than OJ. But I also knew that that was unlikely. That’s why the two childhood friends, Joe Bell especially, lends this immediate air of credibility. He is still loyal to O.J. but he also is very honest about him.

Filmmaker: You have the crime scene photos in the film. I had never seen those pictures before.

Edelman: They have not been seen before. We got the photos from Bill Hodgeman. Hodgeman, who is the deputy D.A. has been giving a presentation about that night to prosecutors or maybe even to police about the case, so he gave Tamara and I this presentation that ends with these photos which we had never seen. And yes, they are horrific. But I also understood very quickly, this imparts something that is so necessary to impart. You can’t avoid this. If you want to be like, “Oh, well maybe he didn’t do this, or maybe there are other people involved or maybe…” Seeing him out in the world after that — I need you [the audience] to rest with that thing. And see what happened. And I think it’s really crucial.

Filmmaker: I think it’s essential. And I don’t usually include crime scene photos in my work, but for this story I think they are essential.

Edelman: And I think obviously they could have been used in a way that would not have been okay.

Filmmaker: Easily. That’s usually how crime scene pictures are used.

Edelman: There’s something about how coldly Bill Hodgeman describes that night in his mind in terms of what happened — his rendering of that scene was so clinical in a way that made it only possible done through his eyes. And without it I would have been loathe to just throw them in there.

Filmmaker: Are you working on a next thing or do you just want to lie in a hammock with a Mai Tai?

Edelman: I definitely just want to lie in a hammock with a Mai Tai. I’m pretty exhausted. It’s not only the amount of work but the subject matter is so dark that I actually don’t even know how it’s affected me, living with these things for the last couple of years.