Back to selection

Back to selection

“Part of My Job Was to Provide a Safe and Warm Atmosphere”: DP Ed Herrera on Whirlybird

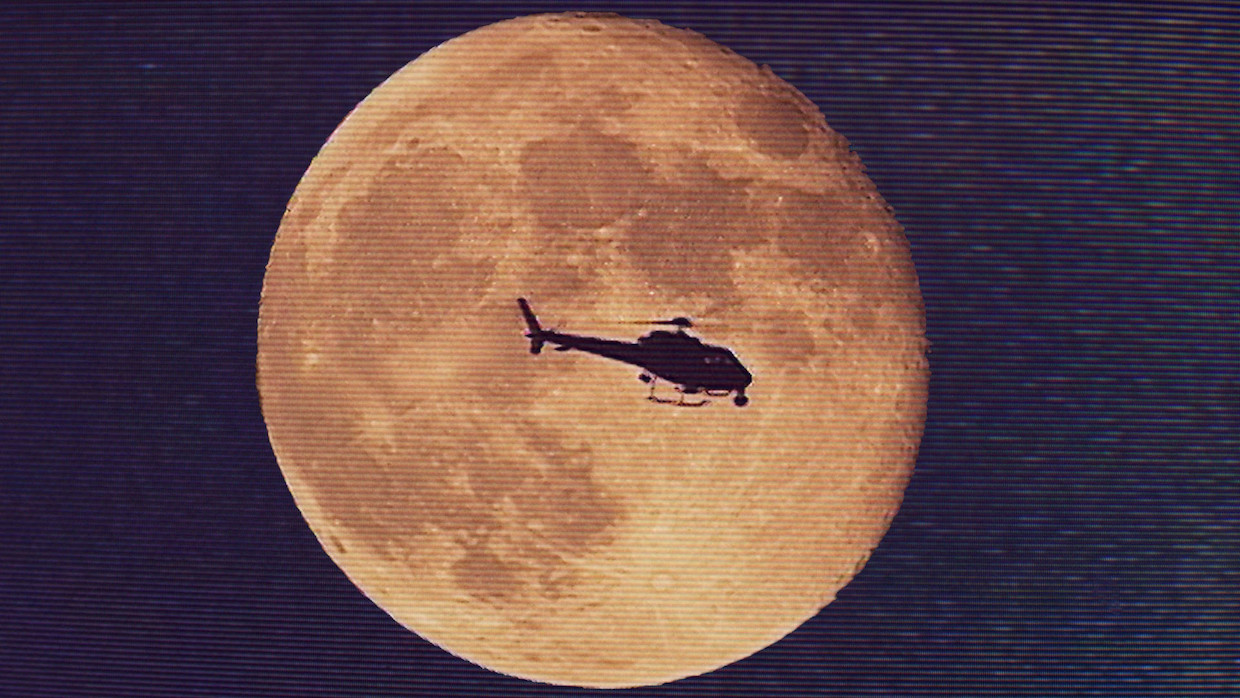

A still from Whirlybird by Matt Yoka (courtesy of Sundance Institute)

A still from Whirlybird by Matt Yoka (courtesy of Sundance Institute) Some of LA’s most iconic news stories are literally shown from different heights in Whirlybird, Matt Yoka’s debut feature documentary. It chronicles the exploits of married reporting team Marika Gerrard and Zoey Tur, who pursued breaking stories from a news helicopter above the city. Composed of archival footage, home video and interviews, Whirlybird presents history in a new light. DP Ed Herrera talks about the freedom and constraints of working on this documentary.

Filmmaker: How and why did you wind up being the cinematographer of your film? What were the factors and attributes that led to your being hired for this job?

Herrera: Matt and I met on a VICE docu-series several years ago. We got to travel around the world filming that series, so we really got to bond over time. After our run there, we sort of went off and did our own things. Matt spent the next couple of years developing Whirlybird, so by the time he got to the stage of getting a green light on the project, I had just recently moved to Los Angeles. He by chance called me and all these stars sort of aligned. By the following week we were meeting to break down the visual approach of the film.

Filmmaker: What were your artistic goals on this film, and how did you realize them? How did you want your cinematography to enhance the film’s storytelling and treatment of its characters?

Herrera: Matt had a very clear vision for how we should portray the characters within the world of Whirlybird. The goal was always to feel like we were sitting beside the subject, in their private space. We had to imbue the photography with the feeling of earned intimacy reserved for a close friend or a loved one.

Filmmaker: Were there any specific influences on your cinematography, whether they be other films, or visual art, or photography, or something else?

Herrera: We cited Nan Goldin’s color photography from the 1980s as a key reference point to Whirlybird’s visual aesthetics. Goldin’s photography always seemed to feel so personal and private; Almost like we were let into someone’s personal world, where we would have otherwise never had the privilege to experience. There’s something to be said about the intimate nature between the photographer to subject relationship, which is something we strived to define and protect in this film.

Filmmaker: What were the biggest challenges posed by production to those goals?

Herrera: Quite honestly, the biggest challenge was maintaining consistency in lighting throughout an interview period that would sometimes take as long as three days. The challenge was to make the lighting feel natural but all taking place within a consecutive hour and a half of screen time. In a narrative film, we can physically set the scene at the appropriate time of day and light accordingly under very tight margins of control. With a documentary, and especially this one, I could not impose a tremendous amount of artificial lighting and grip equipment—that would affect the atmosphere. This was, after all, usually someone’s home, so we had to be mindful of that kind of thing. People have a hard time opening up in general, let alone in front of a camera—and in most cases, in front of a forest of equipment and monitors. We stripped as much of that as we could. I feel that part of my job was to provide a safe and warm atmosphere for the trust to happen between Matt and his subjects.

Filmmaker: What camera did you shoot on? Why did you choose the camera that you did? What lenses did you use?

Herrera: We shot Whirlybird single camera style, on the Alexa Mini. I’m very partial to Arri cameras for their look and texture (especially at around 1600 iso), so it was a given that we would use it for this project. The Mini, in particular, was a great camera body to use because of its compact size. Size was everything, as we tried to impose as little as possible in every location. I used the Panavision PCZ 19-90 zoom because it gave me great range while still being fairly small in size. That zoom lens is soft in a painterly way, which helped me bridge the gap to a more analog feel. Matt really wanted to keep a gentle, handheld feel to the interviews, so we came up with this small suspension rig—basically a parachute cord coming from above that would suspend the camera by a carabiner hook. That allowed me to keep a loose feel without carrying the physical camera weight for what could have been as much as three straight days for a single interview.

Filmmaker: Describe your approach to lighting.

Herrera: We wanted the interiors to feel like natural sun filled rooms, but with a sense of mood and contrast. I usually augmented the sun with an HMI through a narrow Leko lens to replicate the sun hitting our character, and then covered the ceiling and any wall that was off camera in black to absorb any extraneous bounced light. That way, we could feel the angle and intensity of the “sun” in the room, while deepening the shadow side of the face a little more dramatically.

Filmmaker: What was the most difficult scene to realize and why? And how did you do it?

Herrera: Every scene, because we’re dealing with real people, and not actors.

Filmmaker: Finally, describe the finishing of the film. How much of your look was “baked in” versus realized in the DI?

Herrera: What you see is what it was. The glass we used gave us a little extra character but more or less its very faithful to what it felt like to be in those spaces. The most we ever did in the DI was to balance out the luminosity and contrast of every scene to preserve a sense of continuity. We dialed in the skin tones to feel as though they were captured on celluloid, which was a testament to our colorist Luke Cahill’s skill in bringing out a more chemical feel to the Alexa image.

TECH BOX:

Film Title: Whirlybird

Camera: Alexa Mini

Lenses: Panavision PCZ 19-90 T2.8 zoom

Lighting: Joker 800 HMI, Bug a beam kit, Astra bi-color LED’s, negative fill.

Processing: ProRes 4444

Color Grading: DaVinci Resolve