Back to selection

Back to selection

“It Had to Show How We Rip Each Other Apart”: Galder Gaztelu-Urrutia on His Vertical Class-Warfare Netflix Dystopia The Platform

The Platform

The Platform Access to food serves as the most basic representation of wealth in Galder Gaztelu-Urrutia’s The Platform, a dystopian allegory for economic inequality in which a vertical prison pushes people to the edge of their humanity.

Inside the Vertical Self-Management Center (Centro Vertical de Autogestión)—as the facility is formally known in the fiction—two individuals are housed per level, and each is allowed to bring one personal item with them. They receive sustenance once a day on a floating platform. Those on the higher floors fill their bellies with disregard for the unfortunate ones below. But once a month each pair wakes up on a different level, a twist that evidences how quickly the oppressed become victimizers.

As explained to Goreng (Ivan Massagué), the protagonist of this forsaken social experiment, from his vicious and witty cellmate Trimagasi (Zorion Eguileor), desperation breeds violence and cannibalism. However, though the horrors are unspeakable, Goreng is a catalyst for morality and justice—even if force-fed—who begins a radical and dangerous proposition to prove a more egalitarian microcosm is possible.

Initially conceived for the stage by co-writers David Desola, whose credits include the Mexican two-hander dramedy Warehoused, and Pedro Rivero, artist and animation filmmaker behind the similarly brutal Birdboy: The Forgotten Children, the concept a timeless one. The film’s Spanish-language title, El hoyo (“the hole”), speaks both of the space in the middle of every stacked-up cell that allows the lavish dishes to descend through the structure, and to being in the pits, down to a state of hardship, into the abyss this place leads to.

Since its Netflix debut on March 20, in the midst of a global crisis, The Platform has sparked much debate over its ambiguous ending, one that refuses to hand out a comforting sense of hope, and the hard-hitting truths it grapples with in a genre context that feels increasingly parallel to our reality. The Spanish director, previously a producer and commercial director, fed Filmmaker some raw insight into the excruciating rewriting process and the logistical inventiveness the production entailed.

Filmmaker: Tell me about how the fascinating concept of a vertical prison, specifically the set, was acc-omplished on an independent film budget. Was it an elevated construction that gave the illusion of more levels above and below? Or was it achieved mostly through digital effects?

Gaztelu-Urrutia: The design process of the prison, the hole, was key to getting the most out of every euro in our budget. Functionally, the entire construction was millimetrically calculated with its moveable walls and nooks so we were able to shoot 99.9% of the film with the camera on our shoulder, handheld, without any other filmmaking machinery.

We built two levels with a space at the bottom to place the scissor crane that propelled the platform, which was later digitally erased in post-production. 80% of the film we shot on Level 1, and, when we needed to shoot pointing the camera down, we went up to Level 2. Based on these two levels, we generated the endless levels seen on screen adding via post-production techniques for layer composition and 3D imagery.

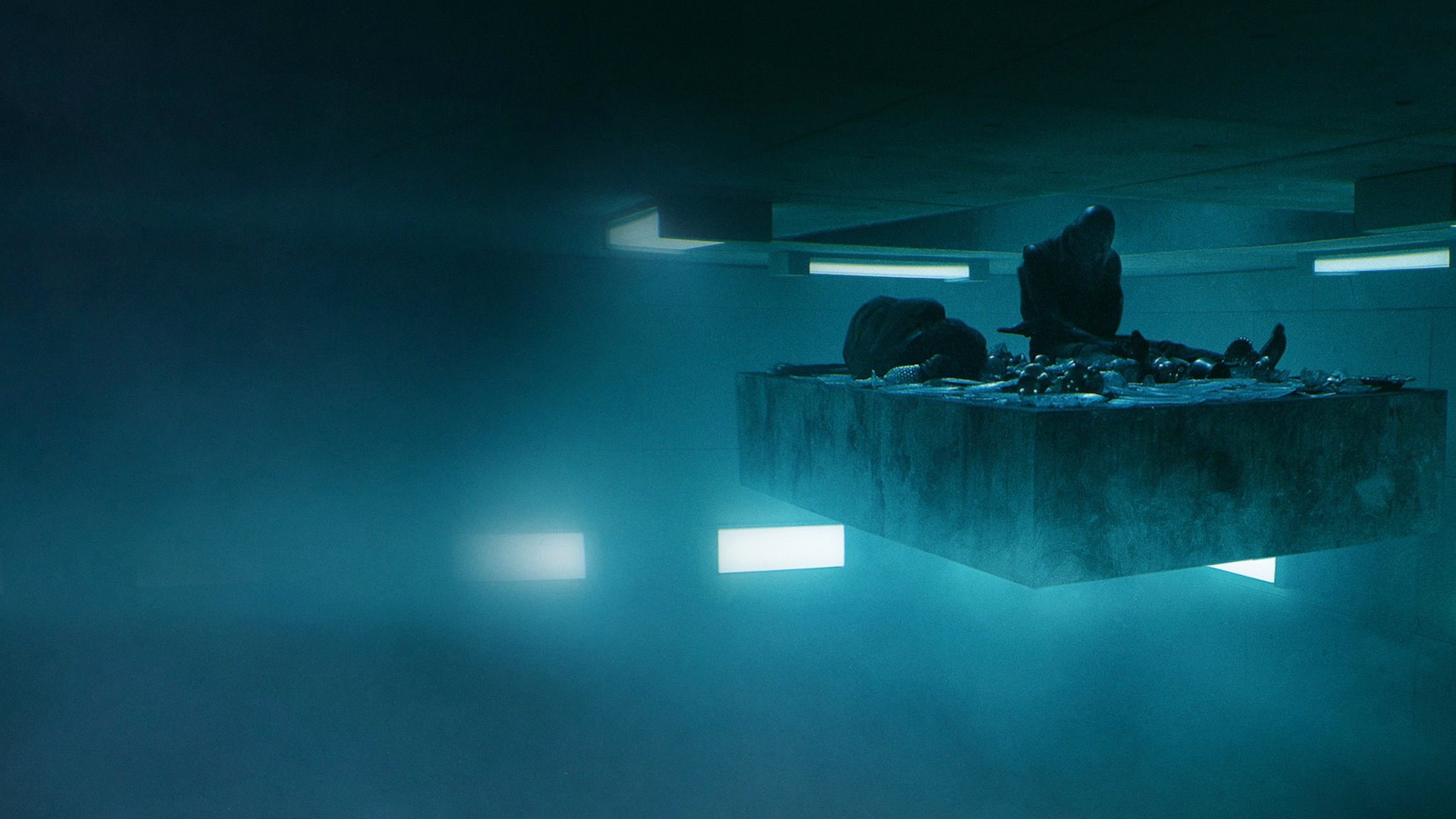

Artistically, the design represents the dehumanized coldness of the Vertical Self-Management Center—an outstanding accomplishment by art director Azegiñe Urigoitia. When we started thinking about the structure of The Platform, we tried to do it from the point of view of the fictional architect who designed it, from the point of view of the society that conceived it.

The structure had to be efficient, durable, impregnable, indestructible, cheap, so it was not difficult to conclude we had to use modular blue-gray concrete slabs. We thought of a construction of very simple geometric lines. The plan of each level is rectangular: nine meters long by six meters wide. That is, a ratio of “1/1.5”. This format is repeated over and over again, achieving a very graphic and repetitive aesthetic. The platform has exactly the same proportions, and so do the wall panels, the toilet, the mirror, and the tables. The sconces, beds, and sinks have that ratio multiplied by 1.33.

Filmmaker: Similarly, another production design aspect that’s intriguing is the food on the platform. Could you describe the thematic intention and practical approach to this element, which powerfully stands in for wealth?

Gaztelu-Urrutia: The food was treated as another character in the story, one that is aesthetically antagonistic to the architecture of the prison. We worked with a warm palette of ocher ones. It’s liquid, organic, and irregular, and it’s presented on mannerist, fanciful, Versailles-worthy tableware with a markedly decadent halo. In the highest levels, food is an object of excessive, almost erotic, opulent desire. It’s perfect to be desecrated, destroyed, to end, further down, in what’s abject, in complete aberration. From a technical standpoint, there is fictional food (props) and real food mixed together.

Filmmaker: The grotesqueness of the leftover food on the platform, and the very primitive way in which prisoners consume it, adds a certain brutality to the act of eating.

Gaztelu-Urrutia: That’s correct. Aside from to the aforementioned production design, I worked extensively with the actors, most notably Zorion, to underline the primitivism of the act of eating. Later, obviously, that primal act was reinforced with sound effects thanks to the expertise of sound post-producer Iñaki Alonso and composer Aranzazu Calleja. Music and sound effects coexist harmoniously, so that it’s sometimes impossible to tell them apart.

Filmmaker: There’s gruesome violence in the story. Were there any concerns or debate over how graphically these acts of carnage and cannibalism should be presented?

Gaztelu-Urrutia: If the hole is a reflection of our society, it couldn’t hide the violence. It had to show how we rip each other apart.

Filmmaker: While the horror unfolds in reduced spaces, there’s a visual dynamism to what’s on screen and how it’s shown, be it the flashbacks or disturbing apparitions. What was the mandate or parameters you and cinematographer Jon Domínguez followed here?

Gaztelu-Urrutia: We depart from a premise of simplicity. The film called for a simple staging without aesthetic artifice. In this sense, there is no shot that couldn’t have been done 60 years ago. At first, the story is told with very tight shots and we show the space, little by little, keeping the mystery, paralleled to the information that characters’ dialogue provide, so that we invite the viewer to enter the hole, this prison, organically. Once inside, we close all doors and show the four walls. Now no one can leave.

In addition to the camera, Jon did a great lighting job creating an oppressive and overwhelming atmosphere. There are countless photographic details that delve into the emotional state of the characters. For example, chromatically, the blues on the upper levels tend to be turquoise, while those on the lower levels are darker. It is like the sea: the color on the shore is gentle and that of the sea is dark and cold.

Filmmaker: Upon first engaging with the screenplay, did you instantly foresee the logistical compilation of realizing the vision, or where you more concerned with the philosophical notions and the narrative mechanics that came with it?

Gaztelu-Urrutia: The original idea is from one of the screenwriters, David Desola, who together with the other screenwriter, Pedro Rivero, wrote a script for a play. This work was never produced for the stage, so the writers sent the script to the producer, Carlos Juárez, who loved it and sent it to me immediately. I was very impressed with the analogy of the levels and the potential of the script but, at the same time, it was clear that the text required deep rewriting to make it into a movie.

From then on, being honest, it was a really torturous ordeal that lasted two years. David, Pedro and I argued a lot. . They are two friends I admire but who, sometimes, honestly, I want to strangle. Each defended his point of view tooth and nail. More than once we were about to abandon the project. There were conflicts regarding both core and anecdotal elements. There were days when I loved them and others when I hated them. Now I remember that period with some affection, but it was hard.

Finally, little by little, I started rehearsals with a version of the screenplay I felt relatively comfortable with. The actors and actresses contributed a lot and we made quite a few changes. During the shooting we also changed things, and finally, in editing, we finished outlining what you have seen.

Filmmaker: The Platform is an incredible allegory about economic inequality and how its roots lie in the worst human nature. The film’s release aligned with a global crisis where people are now consistently questioning power structures. Do you think that the reception towards the film has to do with this cultural and social moment?

Gaztelu-Urrutia: Genre cinema is a great vehicle to protest. When we premiered the film at the Toronto International Film Festival in September of last year, many people told me it was the ideal historical moment to release it because of the perceived inequalities in society today.

To which I replied that if we had premiered at any other time, it would also have been the best moment, because we are always in the historical moment in which there are the most social inequalities. In other words, there is more and more inequality, or, at least that’s how we perceive it. And now, with the launch on Netflix, they tell me again that it’s the best time to release given the strange situation that the world is experiencing.

I believe the film can be understood in the same way at any point in time and anywhere, because we all live and understand injustices in a similar way. With the cards we were dealt, from our level, we all suffer them, and, unfortunately, directly or indirectly, we all exercise them. If on our platform, instead of food, we had put toilet paper or facemasks, we would be talking about the same thing, about the selfishness that lies deep in our hearts.

Filmmaker: To that point, a strong point is made in how even after having suffered in the lower levels; prisoners become oppressors as soon as they get a taste of abundance.

Gaztelu-Urrutia: Unfortunately, we are the most miserable species that has ever set foot on this planet and I don’t think we will change. We are fearful animals and if you give some power to someone who has lived their entire lives in fear, they are likely to become a motherfucker.

Filmmaker: Among the cast, Ivan Massagué, and especially Zorion Eguileor are peculiar actors playing nearly surreal characters. Did the process of creating that dynamic of power and despair between them involved filming chronologically?

Gaztelu-Urrutia: It was shot chronologically to facilitate the emotional and physical development of the characters. The protagonist, Ivan, appears in practically every shot of the film, and during the shoot, over six weeks, he had to lose 12 kilos to give credibility to Goreng’s physical and psychological deterioration. Imagine how hard it is to act in movie that in itself demands so much of you, while simultaneously following the most severe diet of your life.

If Ivan’s work is meritorious, Zorion’s is no less so, especially considering that a week before we started production we had to change actors and we found him. In other words, seven days before we began filming, Zorión didn’t know of the existence of a movie called The Platform. My pledge was to work that pain with them to the point of exhaustion, in order to enhance the perverse chemistry that those two sides of the same coin needed to have.

Filmmaker: For Trimagasi everything is “obvious.” Does that speak to the fact that he accepts the status quo or what does that interest for what he considers obvious tells us about character and this world?

Gaztelu-Urrutia: Trimagasi is the hallmark of our film. It’s what makes it different from all other movies in the same vein. The cynicism and empathetic irony of this despicable—and adorable—individual makes him feel strangely close. We all have a little bit of Goreng and a little bit of Trimagasi, and each one of us has to decide which of them wins our own internal battle—if you can choose, of course. Upon our first viewing, when we look at Goreng, we see what we want to be. And, when we look at Trimagasi, we see what we are. Yes, I said first viewing, because the film is designed to question that premise in repeated viewings.

Filmmaker: There’s been much talk about the film’s ambiguous ending. You are not hopeful about our species, but could there be a glimpse of optimism in it or should our society radicalize because no revolution happens completely peacefully?

Gaztelu-Urrutia: In the film, the character of Imoguiri tries to set in motion a peaceful revolution, but runs into the inherent selfishness of our species. That selfishness is not only perceived in the upper levels, it’s also seen in the lower ones that despise those who are even lower, being the great desire of the majority to climb positions, whatever the cost.

A revolution implies a regime change, making it practically impossible to do it in a peaceful way. Perhaps there are individuals who would give up their position voluntarily to achieve a more egalitarian society. However, for the group that should give in, that’s very difficult to collectively agree on. We are all selfish, but there are some among us who are very selfish. The latter, the most selfish, light the fuse and the fire of selfishness spreads easily among the others.

I’d like to say that The Platform is not a social critique. It’s a social SELF-critique. I am also in the hole and I see myself reflected in many despicable aspects of the film. Sometimes I surprise myself with shameful classist, racist, sexist thoughts…but I will improve, I promise.