Back to selection

Back to selection

“Male Science Fiction Movies are About Men Having a Romance with Their A.I. Women”: Shalini Kantayya on Coded Bias

Coded Bias

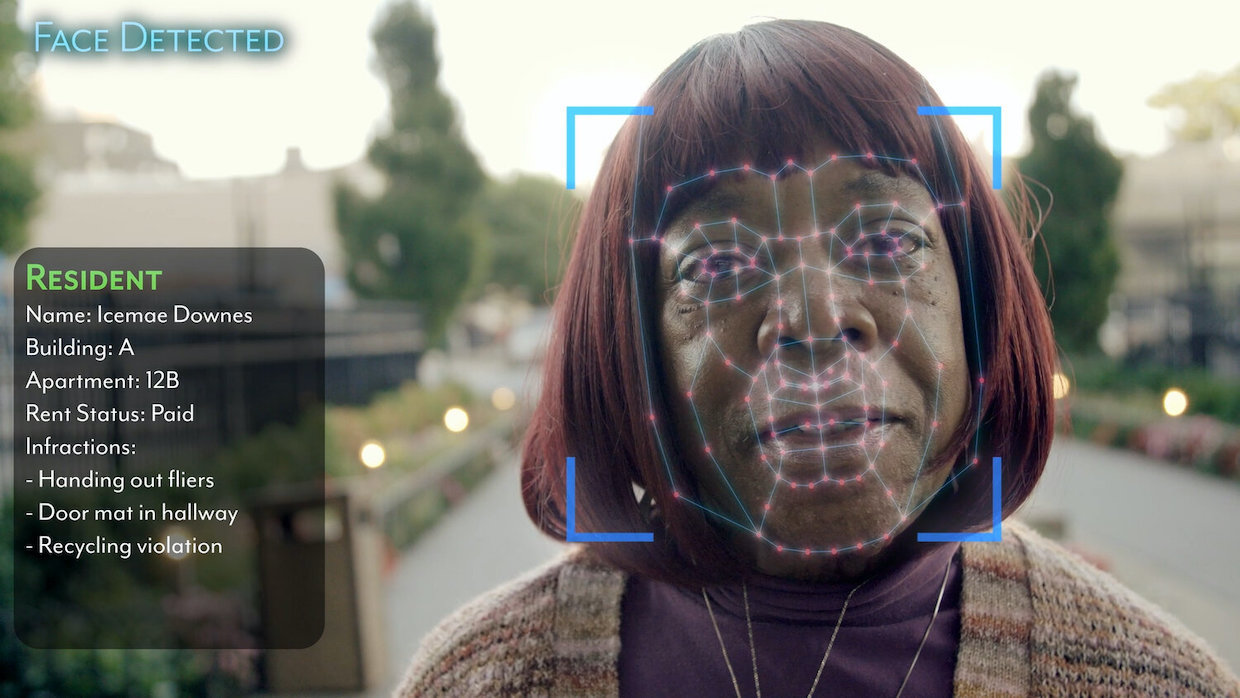

Coded Bias A.I. and “machine learning models” can decide who is accepted into college, who gets housing, who gets approved for loans, who gets a job, what advertisements appear on our social media and when. The extent of what A.I. dictates in our lives, and how, is unfathomable to us because it is essentially unregulated, yet we have accepted these invisible systems into our lives with incredible faith and speed. We trust the algorithms, assuming their mathematical functions lack the ability or will to hurt us. But activist and filmmaker Shalini Kantayya’s film Coded Bias shows us how these systems will always be, for better and for worse, reflections of the people who made them. Algorithms and A.I., Kantayya reveals to us, are prone to recreating and even automating our worst human biases.

With no government regulation, algorithms and A.I. that discriminate against women and people of color can freely enter the world. When these biases in the system are discovered after they’ve already been implemented, programmers and the companies who employed them are not at fault. It is written off as a technical issue the programmer did not intend; there are no legal repercussions. But as is typically the case in many fields, Black women are at the head of the charge for improvements in the tech industry. Computer scientist and poet Joy Bualomwini (who calls herself a “poet of code”), started the “Algorithmic Justice League” when she discovered her facial recognition software wasn’t recognizing her face because it was biased towards white complexions. She ends the film testifying before Congress and scaring Democrats and Republicans alike with the dangers of unregulated tech.

Another reason these algorithms are so untouchable is because the language surrounding them is abstruse and its functions hardly ever transparent to consumers. Kantayya tells us how she streamlined this technobabble with Coded Bias so that we can understand the havoc A.I. wreaks every day in the background of our lives. In doing so, the algorithms feel much more manageable and maybe a little less horrifying because of that.

Filmmaker: As the election came down to the difference of just thousands or hundreds of votes, it is hard not to think about what Coded Bias shows about social media’s potential to sway elections one way or the other.

Shalini Kantayya: Zeynep Tufecki recites this Facebook study that was published in Nature magazine in 2010 that shows the difference between the small, incremental change of showing your friends faces with an “I Voted” sign that Facebook implemented [versus] not showing their faces. They found out that Facebook could sway in excess of over 300,000 people to the polls. Basically, what that goes to show is how these imperceptible changes in the way the algorithms work can have very real outcomes on human behavior.

Filmmaker: The doc also shows how unregulated tech is a rare mutual fear between Democrats and Republicans.

Kantayya: AOC, left liberal from Queens, is agreeing with Jim Jordan, conservative Republican from Ohio. There’s this scene where Jim Jordan says, “Wait a minute. 117 Million people are in a police database that [police] can access without a warrant, and there’s no one in elected office overseeing this process?” That was a rare moment where I hoped both sides of the aisle could see the issue.

Filmmaker: How do you start into this? Is your shooting schedule the first skeleton of the project?

Kantayya: No. I couldn’t talk to people at parties about what I was working on because it was so hard to describe. I think I started with a few core interviews, maybe four, and from that process fell down the rabbit hole, went deeper and deeper into the story and built the arc from that. I think it wasn’t until when Joy went to D.C to testify before Congress that I had a documentary. I had a beginning, middle, end and the character had gone on a journey. [laughs]

Filmmaker: Who or what decided when your shoot ended?

Kantayya: I am the person that decides. I think getting to Sundance was a big marker for the film being finished. I’m so grateful that we made it in time for the premiere, because it pushed us do so much work in a short amount of time. But I think the film wasn’t really finished at Sundance. We were supposed to play at SXSW, which I wish we could have done, but I don’t think the film was finished until June when we finished it [for] the New York Human Rights Watch Film Festival. This was the director’s cut, and I did feel the difference in how that cut of the film was received.

Filmmaker: This film is a brisk hour twenty, and this is the kind of film whose goal is to get in front of many people as it can.

Kantayya: I thought a lot about how to make the film palatable. It has a lot of dense subject matter and it was such a rigorous edit in so many ways. But it was really important that the film was palatable, and we made some really hard choices. There are so many gems on the cutting room floor, and I was one of the editors. I was committed to making a film that you want more of.

Filmmaker: How much or little of an expert do you have to become to facilitate this best to a mainstream audience?

Kantayya: I still have this humility speaking about it. I’ve now spoken to Stanford’s Human Centered A.I. Institute. I’ve spoken to some really astute engineers and it’s always very humbling to me. [laughs] The cast in Coded Bias are some of the smartest people I’ve ever interviewed; I think there are 7 PhDs in the film. They have advanced degrees in mathematics and science. But I hope the film levels the playing field. When I was at Sundance, someone at Google said, “We’ve been having this conversation internally and your film made it a conversation we can have for everyone.” I hope the film makes people feel that they don’t need a degree from Stanford to understand the technologies that will impact civil rights and democracy, our lives and opportunities in real ways.

Filmmaker: Because so much of the language in these interviews can be abstruse, how much do your editors also have to become experts to even begin to know what they’re working with and how?

Kantayya: I edited a lot of the scene work and big structural work with the interviews. They were so rigorous and dense, so I did a lot of that work myself. My editors, Zachary Ludescher and Alex Gilwit, effortlessly work between editing and special effects. They have this incredible ability to work between mediums. There were some scenes we weren’t sure would work until the special effects were roughed in. So, I was really lucky to have two editors that were really astute at special effects as well.

Filmmaker: You highlight hero Joy, the primary subject of the film and part of the “Algorithmic Justice League,” by sometimes shooting her in slow motion.

Kantayya: I feel like one of the most beautiful things about documentaries is that they make heroes out of real people. I was happy to shoot that in a very stylized way. In a documentary where there’s so much beyond your control, I’m always grateful when there’s a chance for me to control some of the elements.

Filmmaker: Did getting funding for a doc ever feel daunting and undoable to you?

Kantayya: Documentary has had a ladder, I think. Coded Bias is 100% funded by foundations. In the beginning, I went through the front door with applications. I’m not a filmmaker that has enough rich friends and access to capital, so I did it through the foundation route. And I did build a career like that, through small grants, always trying to overdeliver until I got the reputation to do bigger grants. I don’t think it’s the easiest path, but it is a path that’s open to everyone. Limitations define your creativity, and you have to work with what you have. But I’m happy when they compare this film to The Social Dilemma, because it was certainly made at a different scale.

Filmmaker: You were one of the last films to get a proper, theatrical, festival premiere when you premiered Sundance.

Kantayya: Getting to premiere at Sundance is amazing under any circumstances. We didn’t know it was going to be the last [in person] film festival for years. [laughs] But I’m also grateful because it informed how we reedited the film. Getting to watch the film with an audience, and feel them with the film or feel for moments when I may have lost them, really informed how we reedited Coded Bias. Like every filmmaker, I miss the movie theater, and we’re just trying to reinvent ourselves in this new environment.

Filmmaker: Early in the film you show a montage of science fiction films to show how the tech industry aims to manifest the tools and futures those films envisage. I realized all of the films you show were directed by white men, so the bulk of the visions of the future we try to manifest is a future predominantly envisaged by white men.

Kantayya: What I learned in the making of Coded Bias is that there’s always been this conversation between science fiction writers and technology developers. Marvin Minsky at MIT labs was in conversation with Arthur C. Clarke and was the one who actually made HAL in 2001. What I feel is that both technology developers and science fiction artists have been limited by the white male gaze. It’s something we talk about in cinema with “Hollywood so White” and other movements. I think that can restrict imagination. Joy and I were joking that a lot of these male science fiction movies are about men having a romance with their A.I. women, including some of my favorite films like Blade Runner. [laughs] We also geeked out about what science fiction by women would look like. But I hope Coded Bias unleashes the genius of the other half of the population and stretches our imaginations. I think by recentering the conversation on women and people of color, who happen to be the ones leading the fight on bias in A.I., it shifts our imagination about what these technologies can be.

Filmmaker: Can you talk about building the arc of the A.I. narration that begins the film clean and objective and becomes distorted, more biased, and eventually racist and misogynistic over time?

Kantayya: I was constantly thinking about how to keep a cohesive narrative structure when there are so many storylines and geographies. Through research I discovered Tay, a real chatbot that became an anti-Semitic, racist, sexist nightmare. [Tay was a chatbot designed by Microsoft and released on Twitter, that learned from Twitter users to post inflammatory racist and misogynistic tweets and was shut down within 16 hours of its launch] Half of the film uses the voice of Tay and its actual transcripts from the Taybot. Then, about halfway through the film, the voice of the chatbot morphs. Tay dies and it becomes this other voice, which is a woman’s voice that eerily sounds a bit like Siri. That’s written narration. The A.I. as a narrator was a device inspired by 2001 that comments on what the HAL of today is. [laughs]

We have to tell people that the A.I. narration is a reference to HAL from 2001: A Space Odyssey, because it became known to me that a lot of young people have not seen 2001. [laughs] Oh my god! It was only through showing my film to high school kids. I did a hands up to see how many had seen it.

Filmmaker: And there were zero hands up?

Kantayya: Yeah. [laughs] So I was like, basically you didn’t get the reference.

Filmmaker: Another idea in the film, is that this tech is just a reflection of us. It is not this separate and magical thing as it’s been imagined in pop culture, it has inherited all its programmers’ weaknesses and biases. The difference is that those biases are automated, or that there’s no human element where the algorithm questions if it’s wrong.

Kantayya: Human bias can be coded and we all have it. We often don’t realize it. Steve Wozniak’s wife got a different credit score than him on the Apple Credit Card and he was like, “How can this be? We have all the same money, all the same assets, everything.” It could be because women have a shorter history of credit in the US, or a shorter history of having mortgages. But the computer was somehow picking up on historical inequalities, and the programmer didn’t know that, so it’s an example of unconscious bias. A similar thing happened with Amazon. They installed a sorting system for resumes and were like “This is great, this is going to undo the human bias that we all have,” and lo and behold the A.I. system is picking up on who got hired, who got promoted, who had job retention in the past and it discriminated against any candidate that was a woman. It had the exact opposite impact. It just goes to show that even when the programmers have the best of intentions, the A.I. can pick up on unconscious biases and historic inequalities.

Filmmaker: Finally, I just want to confirm, the working title for this film was Racist Robots?

Kantayya: [laughs] I tested it. I loved that title so much! [laughs] But people wouldn’t let me keep it.