Back to selection

Back to selection

Anxiety of the Outspoken: Director Kathryn Ferguson and the Example of Sinéad O’Connor

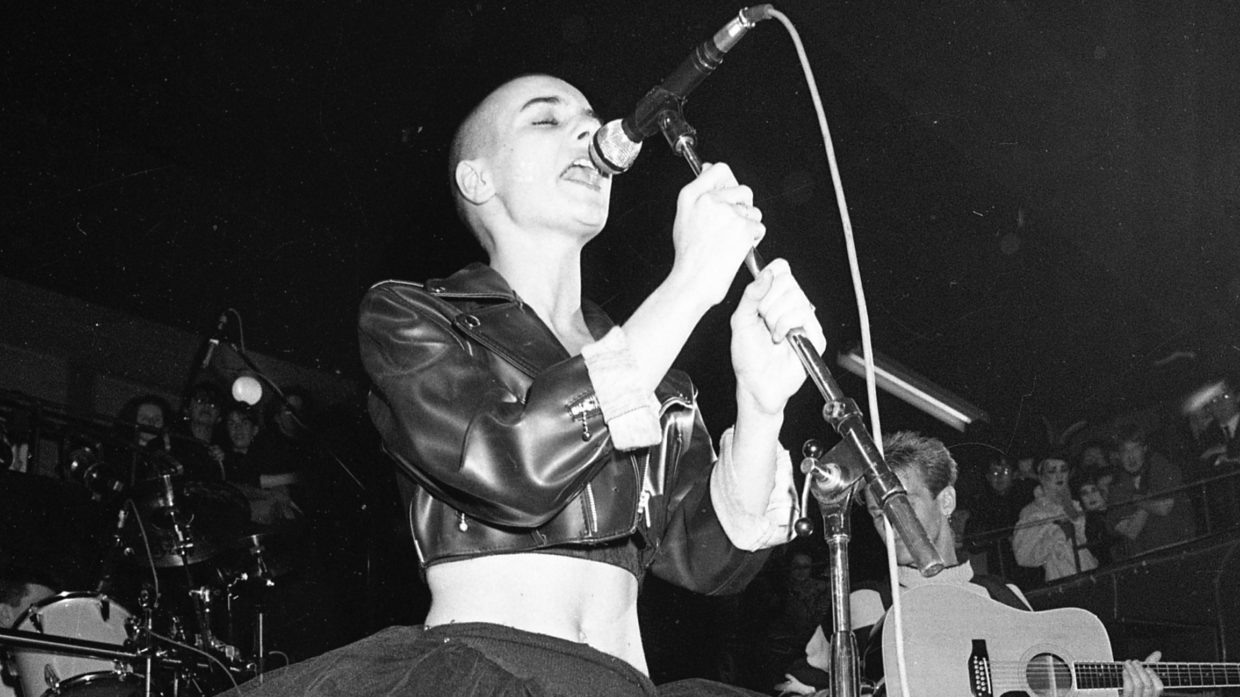

Sinéad O'Connor in Nothing Compares (Photo: Courtesy of Independent News

and Media/SHOWTIME)

Sinéad O'Connor in Nothing Compares (Photo: Courtesy of Independent News

and Media/SHOWTIME) It would be nearly impossible to name another musical performer deserving of a deep dive into her formative years than Sinéad O’Connor. Every step of her life — shuffled between an array of parochial schools, a childhood subject to her mother’s chaotic transference of her own abusive childhood onto her daughter — would in retrospect seem to have been an accretive stage in O’Connor’s becoming. A popular culture firebrand, demonized, her message mischaracterized to the point of parody, met with a withering disdain in the highest corners of western media, O’Connor’s own words have always spoken for themselves. Her message has been unwavering and with hindsight has proven more than prescient. The only thing that has changed with time is her audience.

As a reparative measure. Kathryn Ferguson’s film Nothing Compares seeks O’Connor by foregrounding her own voice. The film takes its name from O’Connor’s biggest hit, a song written by Prince and which his estate refused to license for the filmmaker’s use — a decision clarified quite bluntly by Prince’s family in a statement by his sister, who said, “… I didn’t feel [Sinéad] deserved to use the song my brother wrote in her documentary so we declined. His version is the best.” A mosaic of archival footage and artful interstitials, guided by an extensive voiceover interview with the subject, the film places an elegiac sound design over outtakes from O’Connor’s iconic video, famous for its single, unplanned, “tear felt around the world.” The documentary covers O’Connor’s turbulent Dublin childhood and adolescence, her early musical output that positioned her for stardom, and the seismic fallout that followed, leading to a widely publicized but unspoken form of public exile. It builds to a reckoning, culminating in her October 1992 appearance on Saturday Night Live, where she infamously opted not to sing her hit single, and instead recited the song War by Bob Marley, the lyrics themselves a quote from Ethiopian emperor and Rastafarian messiah Haile I Selassie, and then tore up a picture of Pope John Paul II before the camera cut. The firestorm that followed included public threats from people like Frank Sinatra and Joe Pesci.

Ferguson’s film, her feature debut after working extensively in the fashion world and making commercial short films and music videos, leaves no question as to its prerogatives. O’Connor’s blunt confession of pain that opens the film sets the stage and serves as a revelation for anyone with dismissive associations of the singer. It’s also a reckoning for O’Connor herself, along with those who like her, both those victim and witness to abuse as children. The foregrounding of O’Connor’s own seminal trauma bullhorns the indictment of Catholic institutions at large — as an adolescent girl, O’Connor even spent time in the horrific Magdalene Laundries, when there seemed to her father no other recourse to control her behavior — and centers its focus on the bottom line: O’Connor was young and impressionable when she saw firsthand how the vulnerable could be shut away and ruined by the powerful, and it was the example of Ireland and the role of the church as oppressor, in concert with British occupying forces amid the Troubles, that prepared this young girl from Dublin for taking the world stage and giving her tormentors everywhere the V sign.

Filmmaker spoke to Ferguson about the inflection point of her film, the filmmaker’s responsibility in contradicting the public perception, and the impact of pioneering video director John Maybury on the film’s visual conceit. Nothing Compares is currently playing on Showtime.

Filmmaker: You’ve spoken about how Sinead O’Connor’s presence meant a great deal to you when you were young. Your film could be a real turning point for how her legacy as an outspoken performer, someone of integrity, is viewed. Particularly in the West, as she and the flashpoint moments in her career were portrayed in the States, her point of view was completely absent, no matter how she tried to put it forth in a composed, articulate way. Was her background and position known in Ireland? Was she beloved or controversial there as well? And was this a corrective endeavor for you?

Ferguson: Absolutely. The story really needed to be looked at through this contemporary lens. It always felt very skewed to me. Particularly when we went on our deep dive through the archives, all the research, it just wasn’t adding up to me — the headlines and portrayal of her and then how she appears in the film. She’s clear as a bell and very succinct. She speaks so beautifully.

Filmmaker: Right, and yet she’s treated as a trifle by these media personalities. I’m thinking mainly of people like Charlie Rose saying he’s not going to ask her about her haircut, then asking her, and the way The Late Late Show host Gay Byrne talks to her. It’s so disrespectful, it’s really startling.

Ferguson: Well the thing is, I think she was telling people her background and her history long before the events in 1992. I just don’t think people were listening. There’s loads of interviews where she’s being very honest, but the abuse scandal in the Catholic Church broke much later. She was very early to the table with that. But especially with her own upbringing, the transgenerational trauma that she went through and that so many people went through in Ireland, she was always very, very vocal. So I do find it amazing that people were so confused by her actions, because she’d obviously been telling them. They truly just weren’t willing to listen.

Filmmaker: For anyone who knew her through that media prism, it would come as a shock. The dimension she’s given in the film feels very necessary.

Ferguson: In the release of the film, that’s what I’ve found. Exactly what you’re saying. So many people came forward to me to say how important she was to them.

Filmmaker: You come out guns blazing with both the church and the culture of silence surrounding abuse and exploitation square in the crosshairs, right at the start of the picture. There’s no equivocating. It’s not gentle. It’s right there.

Ferguson: She was speaking out against the church and at that time even in recent history, you can really never underestimate the extraordinary influence the church had. People were up in arms and she was seen as being too noisy about that. And we know what happens to women who are too noisy.

Filmmaker: With what the media made of her and her career, it’s a striking contrast. But for so many people, she struck a particularly resonant and painful chord. The line Chuck D says in the film regarding her support for Public Enemy when they boycotted the 1989 Grammy ceremony [O’Connor appeared solo onstage with a PE symbol painted on the side of her head], he makes this distinction where he says she didn’t have any pretense about what she was doing. How there was an authentic feeling guiding and driving her. So many people felt that but probably couldn’t pinpoint it.

Ferguson: She seemed to cut through all the noise and spoke directly to people in a very profound way. Through the music, what she was saying, speaking up for the underdog. All the people who have been so terribly represented or felt not represented. She spoke to that in a very clear, emotional way and touched them. People remember what she meant to them in their formative years and that’s why she was catapulted into superstardom. She was transcendent, beyond being an artist and a singer. John Maybury says when he’s talking about the Nothing Compares 2U video that she cuts through like a sword. It’s heartening to know that so many people have that reaction to her, still.

Filmmaker: She’s so young in all these early images. Her image is extremely vulnerable and yet she’s coming out of the gate in an extremely assertive way.

Ferguson: The response to this 24-year-old woman, the backlash was so intense, and so pronounced, that they obviously viewed her as a threat. They took it very seriously.

Filmmaker: She’s certainly treated like someone who needs to be dealt with and put in her place.

Ferguson: Made an example of. It says to women, don’t stick your head above the parapet.

Filmmaker: It’s hard to imagine anyone in the pop mainstream currently not backtracking, apologizing, getting PR’d into oblivion for fear of the monetary cost of controversy, if even one of these instances were played out in their career today. And O’Connor had so many of these moments where she said things people didn’t want to hear or didn’t like and she never once bowed to ask for forgiveness. A modern performer’s response would be immediate clarification. Apologize and say you didn’t mean what you said. Repair the damage immediately.

Ferguson: Well superstars — and she was a superstar — are expected to be grateful. And she wouldn’t. And that made her quite dangerous.

Filmmaker: In her case, O’Connor took each of these dustups as an opportunity to go further. The Bob Dylan concert after SNL where the fire is still raging and she gets up there and just recites the War lyrics again, is her essentially upping the ante while the smoke has still yet to clear. She never goes back on what she says or does. The integrity is unimpeachable.

Ferguson: It sums her up completely. She was always steadfast in her convictions and she would not apologize, would not play the game, and I think that’s what caused such an uproar.

Filmmaker: The church being this malevolent, untouchable entity in so many people’s lives.

Ferguson: And she had spoken out about it. But you would have had to listen to what she was saying about the Ireland that formed her for that to make sense. It wasn’t a random act. Not at all. It was very deeply rooted. The most deeply rooted thing she had.

Filmmaker: It also seems strange that what sympathies for the Republican movement in Ireland there were in the States were not enough to overcome the more establishmentarian sentiments in media.

Ferguson: But I think it was how far she was willing to go, and that nobody could seem to stop her, that this is what made her a threat. The media did a fantastic job of being very reductive toward all she had to say. When you see her appear on television, she’s very calm, very clear. But the headline is so overly dramatic. Her activism was bold, but she was quiet. Even Saturday Night Live. Yes, it’s dramatic. But it’s considered. The national anthem as well. She wasn’t planning on causing offense. She just didn’t want any national anthem played before her concerts, in any country. It became this other thing. They found this incredibly offensive. Her action was automatically misunderstood. To look at the cause and effect, you look at that action, it had people confused. Because the scandal hadn’t properly broke. It was too ahead of its time.

Filmmaker: I’m interested in your approach to the imaging and the edit, the overall experience of the film. The interstitials are so beautiful, the way they employ video.

Ferguson: I didn’t want you to notice what we shot. I wanted it to be woven through so that you couldn’t tell what was archival and what we had shot and designed.

Filmmaker: They seem archival but then you see the higher definition compositions of the same images and you realize it’s the past and present in the same frame, so clearly. That it’s about how unless addressed, nothing ever changes.

Ferguson: And I didn’t want to have them be literal recreations. I wanted them to be dreamlike. They’re not a depiction of anything except my visual interpretation of what she is saying. I wanted something besides just staging what she went through. And of all the footage we had of Sinéad, it only began in 1985, and that’s already 18 years into the story. We had to accompany her retelling of that time where there was no footage. So it was like making a tapestry or a scrapbook. We shot multiformat, a mix of the era VHS and 16 mmm.

Filmmaker: Innovation in music videos wasn’t something she was recognized for during her heyday, but if you look, it’s there. This was an adventurous time for that kind of visual and there seems to be an ethereal nod to that aesthetic in your own work here, both in the imaging and sound design of the film.

Ferguson: Well alongside Sinéad as a teenager, for John Maybury [director of O’Connor’s video for the eponymous Prince cover], I was also a mega fan. He was such an icon of mine and I feel like his visual language was so groundbreaking at the time. He’s a disciple of Derek Jarman, for goodness sake. I wanted to create anything that we shot as an homage to him, and the work he had created.

Filmmaker: Your subject sums that time up very plainly: She had fuck all to lose because there was nothing anybody could do to her that hadn’t already been done to her. It’s such a massive statement. It doesn’t imply any sort of recognizable nihilism, but the courage of not weighing consequences over an ideal of speaking the truth. She says it herself.

Ferguson: Yeah, well, Sinéad certainly didn’t ask me to make this film. I desperately wanted to. And I didn’t want to make something about a famous person. I wanted to make something about her. The film has my feelings in it as much as hers. And I am sure you can feel, the anger is palpable. Myself, my experiences growing up as an Irish woman, that’s what I was driven by, as much as her example.

Photo: Sinéad O’Connor performing in Dublin at the Olympic Ballroom in 1988, as seen in Nothing Compares, directed by Kathryn Ferguson. Courtesy of Independent News and Media/SHOWTIME.