Back to selection

Back to selection

VIRTUE AND VICE AT THE 2011 CANNES FILM FESTIVAL

Moral questions about science, war, justice, and ethics were at the forefront of some of the strongest international work at this year’s Cannes Film Festival.

Moral questions about science, war, justice, and ethics were at the forefront of some of the strongest international work at this year’s Cannes Film Festival.

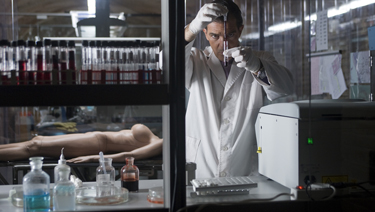

“He’s really not judgmental of his characters at all, is he?” said one party-goer of the Spanish director Pedro Almodóvar. Between bites of warm peaches and pistachio ice cream at a reception for the filmmaker’s sleek, stylish new thriller, The Skin I Live In, party-goers discussed the dark, unsettling tale of a mad scientist (played with panache by Antonio Banderas) who develops a miraculous new variety of human skin and a fraught relationship with his sad, beautiful Frankenstein (Elena Anaya). Although he has never won the Cannes Film Festival’s highest honor, the Palme d’Or, which this year went to Terrance Malick for The Tree of Life, Almódovar remains a perennial favorite here. As the director and his flamboyant entourage made their way into the Lumière Theater, accompanied by Banderas performing a toreador’s moves up the red carpet, the crowd gave them a standing ovation, followed by another one after the screening. The Skin I Live In boasts striking visual settings: an impossibly long staircase lined with fine art leads to a secret chambers; a science laboratory is a glass cube set in an ancient cellar of arching brickwork, and the woods outside a wedding looks like a tangled, primeval garden of earthly delights. It’s the kind of imagery that would ordinarily be associated with on-set cinematography, but Almodóvar shot the film on location in Spain, adding modern elegance to a gender-bending and morality-challenging story that calls into question what it means to take justice into all-too-human hands.

A tiny town is on the verge of being split down the middle between Muslims and Christians in director Nadine Labaki‘s warm-hearted second feature film, Where Do We Go Now? Yet the Lebanese filmmaker, who also plays one of the film’s leading roles, takes a open-minded approach to their conflict. Humorous and warm, with the occasional musical number thrown in, the film follows the story of the creative efforts by the townswomen to keep their men from violent conflict at all costs. Whether it means midnight sabotage against the sole source of news, enlisting the aid of a group of Ukrainian strippers, waging war with pleasant narcotics, or infliciting bodily harm to their own family members, the women in the film stop at nothing to prevent their village from being torn asunder by the violent, religious differences between their husbands, fathers, brothers, and sons. In the film’s most striking scene, they even “trade” religions with one another so that, when their men awake, they find that they are literally sleeping with the enemy. It’s a battle of the sexes, as well as of the sects: can creativity and pacifism trump conflicts that are as old as the hills?

“Don’t see it,” said a friend with excellent taste. “Not only is it boring, it’s deeply morally objectionable.” Reviews that generate passion of that kind generally mean that a filmmaker’s onto something. Was it any wonder that Brazilian director Alejandro Landes‘s Porfirio was one of my favorite films at the festival? In this surprising and affecting work, the title character plays himself: he is Porfirio Ramierez, a middle-aged Colombian man paralyzed in both legs. While he waits for compensation for his injury in the form of check that never comes, Porfirio makes a living selling minutes on his cellphone. He’s the perfect man for the job: everyone always know where to find him and nobody cares if he overhears the details of their personal lives. Porfirio keeps the phone that is his livelihood on a slender chain, and the simple act of securing it each time someone comes to call is a constant reminder of his resourcefulness, as well as his vulnerability. The film studies every element of Porfirio’s life in such exacting, even-handed detail that it caused some walkouts and even some moral outrage–from trips to the bathroom with his son Lisson (played by his actual son, Lisson) to trips to the bedroom with his girlfriend Jasbleidy (played by his actual girlfriend, Jasbleidy), Porfirio’s life seems to be an open book. As such, the film would be captivating even without its shocking extra-textual context, but when the credits roll and its secrets are revealed, Porfirio is balanced delicately between fiction, and documentary, a place where moral and ethical decisions can come uncomfortably close to home.

A trio of yellow car headlights wind through the dark, shadowy steppes in the gorgeous opening shot of Nuri Bilge Ceylan‘s Once Upon A Time in Anatolia. When they come to stop at a well, a cadre of bumbling police officers pile out in the dim light, Keystone Cops as they might have been painted by an old master. When a handcuffed vulpine prisoner determines that this isn’t the location they’re looking for–the right place is marked by a “round” tree–they pile back into the cars and try another spot, and then another. When they eventually find the location they so arduously seek, the site of a grisly burial becomes a revelation. The film’s widescreen compositions are simultaneously restrained and arresting, and it’s easy to get lost in their stark beauty. Ceylan’s leisurely, grim police procedural was slotted on the last day of the festival, so that Cannes attendees who wanted a chance to see the much-anticipated feature were obliged to stay until the very end. Over at least one dinner table that night, however, this Turkish delight, with its muted palette and complicated vision of fairness, was declared the film of the festival. In Anatolia, as in many of the most intriguing films at this year’s Cannes Film Festival, justice was in the eyes of the beholders.