Back to selection

Back to selection

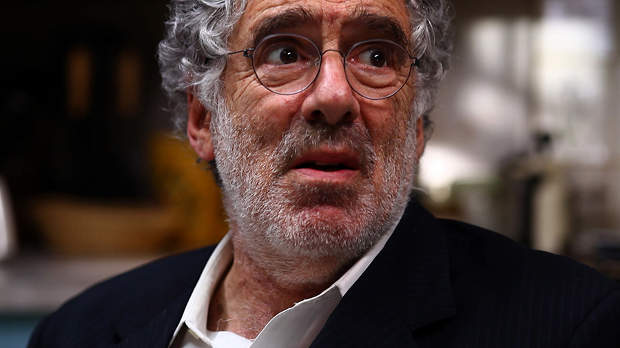

Five Questions with Fred Won’t Move Out Director Richard Ledes

In Fred Won’t Move Out, writer/director Richard Ledes digs into one of American film’s most fertile fields by tapping the improvisational abilities of Elliott Gould. Ledes last directed Gould for the 2008 corporate-crime thriller The Caller, but when he decided to do a smaller, more personal story inspired by his own family, Ledes turned once more to the veteran actor’s versatile skills. The impetus for the film came from the director’s own experience with his aging, infirm parents and their inability to maintain their lives in the house where Ledes had grown up. The characters were inspired by the members of Ledes’ immediate family, with Gould taking the patriarchal role of Fred. But in case that didn’t already create an intimate enough scenario, Ledes went a step further by shooting the film in his parent’s actual house. Fred Won’t Move Out is making the rounds of art houses nationwide through the end of the year, but Ledes is already onto his next project, Foreclosure, starring The Sopranos’ Michael Imperioli; he describes it as “a ghost film that takes place in a house. In a way, these are my two ‘house movies,’ but one is like the negative of the other.”

Filmmaker: Fred Won’t Move Out is a very different kind of project from The Caller; what made you think of Gould for it?

Ledes: Over the course of working with Elliott Gould on The Caller, I began to feel I had an insight into how he worked that made me want to work with him again. I was pleased that we stayed in contact. I knew I had a small sliver of time and I needed to do the film in a shoot-from-the hip improvisational way. Aristotle talks about four types of causality: final, formal, material, and effective. We can call Elliott the material cause, because he was the first actor I had in mind. It was the possibility of exploring improvisation with Elliott that was essential to the project from the start and I never imagined it any other way. The film only came about because of a momentary aligning of certain possibilities, one of which was Elliott Gould’s willingness to do this film.

Filmmaker: For an admirer of Gould’s early-’70s films, it must have been kind of a dream come true to have him working in that way with you. How would you describe his improv process?

Ledes: I can’t really say what it would be like with another director. It was a dream come true for me, as you say. For all of us it was an attitude of irreverence towards the screenplay — not disrespect, but not reverence either. Hell, Elliott accepted on the basis of seven pages and a phone conversation. We shot over three weeks, shooting in sequence. Three acts. Three weeks. Each weekend I’d write the next act for the coming week. How could anyone treat with reverence something so thrown together? Of course, I did have as a compass the very real experience of what my family was going through. I gave the actors the freedom to shape the material, to propose adding or subtracting dialogue.

The only scenes that were completely made up were the ones with the music therapist played by Robert Miller. Robert is a distinguished composer with whom I’ve had the great fortune to work on three films. He has never acted. I remembered from the commentary for Altman’s film California Split that Altman had suggested that non-actors could work well in films as long as they weren’t obliged to memorize lines. Robert has one scene with Elliott Gould and one with Fred Melamed. They were completely improvised without any written dialogue and they are two of my favorite scenes in the film.

Filmmaker: What made you decide to shoot in your family home? Did it feel strange at all?

Ledes: My parents had lived there for over 50 years. There were moments when I made choices about where to put the camera based on experiences from when I was a small boy living in that same house or playing on the surrounding property. Honestly, filming felt like going deep into a cave with a torch and being scared but driven by what I was seeing and experiencing — including the great amount of humor. I operated one of the cameras — first time I’d ever done that.

Filmmaker: You shot the film in sequence – was that your plan from the outset?

Ledes: Once I had decided to make the film using an improvisational approach, I went back and reviewed the work of great directors identified with an improvisational approach… Robert Altman, John Cassavetes, Lars Von Trier, and Mike Leigh being chief among them. Each gives a unique meaning to “improvisation.” Altman always strove to shoot in sequence and I now realize what an incredible difference it makes. It gives the actors and all the creative keys an opportunity to build new ideas into the film as they work. Also, the actors get to build the arc of the film in the process of shooting. It was a revelation for me to work this way.

Filmmaker: To what extent are Melamed’s filmmaker and Gould’s Fred actually based on you and your father?

Ledes: I would say my father served as an inspiration for the character of Fred but I never stopped Elliott and said, “No, you’ve got it wrong.” The characters are made up. Fred Melamed and I had known each other at college many years before, had subsequently lost track of each other, and then were reunited in the making of this film. It was a great joy for me to work with him. The [filmmaker] character’s concerns about the digital and economic transformation of filmmaking reflect my own, but otherwise the character is a fictional creation. The film is a loving portrait of a family but escapes from being maudlin partially because the character of the filmmaker is a bit of a schmuck. This adds humor. Whereas I, of course, in real life am a wonderful person and never laughable.