Back to selection

Back to selection

Hawaii International Film Festival 2012

“Cinema in paradise” reads the freshly marketed tagline of the Hawaii International Film Festival, a statement that encompasses both the delights and distractions of attending a film festival in one of the world’s most scenic regions. (After all, faced with the beaches, greenery and warm breezes of paradise, cinema may often find itself second choice.) To its credit, HIFF keeps the importance on “cinema IN paradise,” not “cinema OR paradise,” blending the usual film screenings, Q&A’s, and even that unavoidable beast, the “industry panel,” with more unique, leisurely outings like outdoor events and local get-togethers designed to connect grateful attendees with the island’s many charms, as writer/director H.P. Mendoza (I Am a Ghost; Yes, We’re Open) notes. “My experience at HIFF is always disarming,” he told Filmmaker. “You land from wherever you come from, and Hawaii just ‘does its thing’ to slow you down and watch you melt.”

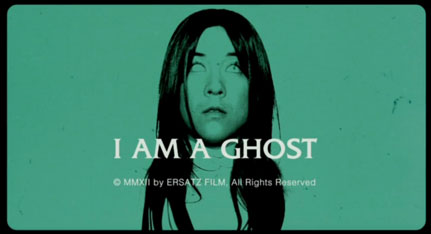

A far cry from the hustle and bro’s of Sundance and SXSW, HIFF merges a comprehensive, wide-ranging program of commercial Asian and Pacific Rim filmmaking with a more select, cherry-picked array of American independent works, many of which match the festival’s intimacy of scope and size. Patrick Wang’s understated gem In the Family premiered at last year’s festival, for instance, after being rejected by over 30 other organizations, and gradually went on to become one of 2012’s break-out independents. Mendoza’s I Am A Ghost provides a similar example of what one can accomplish through embracing the understated and intimate over the grandiose and expansive. The film’s loosely defined “plot”—in an otherwise empty Victorian home, a woman goes about her daily routines, until terror finds her again and again—is the stuff of countless horror films, yet Mendoza cuts out all extraneous filler to instead focus on the genre’s essentials—a house, a woman, constant peril. Shot in one location, with one person onscreen through most of the film (the amazing Anna Ishida, a Bay Area theater actress in her first major film role), I Am A Ghost is a textbook example of how to create cinema from almost nothing except, of course, talent.

Adding a fascinating wrinkle to the horror angle is the film’s use of repetition, repetition, repetition, with Ishida’s daily rituals of egg-frying, house sweeping, and bathroom-mirror gazing replayed throughout the film’s running time, leisurely luring the audience into a domestic haze (and taunting their expectations) until the devil finally—and terrifyingly—comes a-screaming. Here, home is where the hell is. Chantal Akerman’s Jeanne Dielman haunted by the ghosts of Kiyoshi Kurosawa and The Entity, I Am A Ghost has far more on its mind than most horror films, or indeed most American indies. A film buff with an encyclopedic knowledge of both the horror and musical genres (!), Mendoza cites Peter Weir’s Picnic At Hanging Rock and Robert Wise’s The Haunting as two major influences, while the film’s dark, sensual cinematography fittingly echoes the low-budget grain of the American horror wave of the mid-70s. (Its goal was to look like “a ‘70s horror film, shot on HDCAM,” as the director memorably remarked during a Q&A.)

Mendoza also appeared at HIFF as the screenwriter for his Colma: The Musical’s partner Richard Wong’s yuppie satire/romance Yes, We’re Open, in which a longtime couple (Parry Shen; Lynn Chen) dream of spicing up their dimming love through an “open relationship,” only to immediately find their dreams (or nightmares) realized by a swinging, confident, and frankly insufferable duo (Sheetal Sheth, Kerry McCrohan). A wincing satire of the insecurities of young urban professionals, whose frequent visits to farmer’s markets, passionate conversations on international topics, and dreams of threesomes only serve to hide—for a moment—the desperation within themselves, Yes, We’re Open certainly couldn’t have picked a better setting than San Francisco. Both a prolonged eye-roll to the city’s more transparently over-sharing residents and a loving, affectionate embrace of the Bay Area’s overall charm and diversity, the film also serves as a time capsule of the city’s cultural landmarks, with well-known locales such as the Roxie Theater, the Alemany Farmer’s Market, Dolores Park and Green Apple Bookstore captured by talented cinematographer Seng Chen. As with I Am A Ghost, Yes, We’re Open sticks to its strengths—Mendoza’s biting script, ace performances by its four leads, and San Francisco itself—without straining for epic statements or casts-of-thousands moments.

Another film that knows exactly what it is (and more importantly, what it doesn’t need to be), Musa Syeed’s Valley of Saints chronicles life in Kashmir, specifically within the beautiful Lake Dal region, where a young boatman (Gulzar Ahmad Bhat, in reality a young boatman on Lake Dal) dreams of something—anything—bigger than merely ferrying tourists about the lake. Far too often, such minimal “real-life” plots are quickly tainted by the introduction of what could be called “the Sundance Syndrome” or the “European Funder Fallacy,” in which suddenly our young boatman gets involved with vicious gangsters, or armed rebels, or an endangered prostitute, or a precocious young child, and suddenly, voila: a “festival-ready” film emerges, prepped in a slightly more familiar, easy-to-sell manner. To the great credit of Valley of Saints—and to the great credit of Musa Syeed and his producing partner, Nicholas Bruckman—none of that happens; Gulzar’s friend (Mohammed Afzal Sofi) may be up to something illegal, and (this being Kashmir) there’s indeed political protest in the air, but instead Valley focuses on the ordinary, daily life and dreams of those in the region. Cinematographer Yoni Brook’s images find more richness and glory in the way that waterdrops spin along a leaf’s edge, or in how the sun settles along the lake’s rim, than in any forced plot, and give Valley of Saints a lyricism all its own, one far removed from Kashmir’s image of conflict—and just as removed from most narrative-driven American indies. As Syeed, whose family roots are in Kashmir, mentioned in an earlier Filmmaker interview, “I wanted to find a story that helped audiences—and really myself—emotionally connect with a place overshadowed by conflict….Rather than explain the politics, I thought it would be more important that audiences unfamiliar with the region be immersed in daily life.”

“When [lead festival programmer] Anderson Le walked up to the mic to introduce the film, some people in the audience shouted “Hey Anderson!” remembers Syeed of his HIFF experience. “I could tell there was a real sense of familiarity and intimacy in the theater, which made for some of the most engaged Q&A’s we’ve had. I think Anderson has cultivated not just an audience, but a community around the festival, and their investment in the festival really shows.”

Local filmmaker Ryan Kawamoto, whose company Kinetic Films has debuted four features over the past two years at the festival, echoes Syeed’s thoughts. “For my two films this year, we had three sold-out Oahu screenings. There was great excitement and energy before, during and after each show. A large number of the audience hung out afterwards to talk with the filmmakers. There was a true island spirit.” Kawamoto’s two works embraced dual sides of island filmmaking, with his raucous narrative comedy Hang Loose a proudly commercial, populist work, and the documentary The Untold Story: Internment of Japanese Americans in Hawai’i a more traditional, straightforward look on one of Hawaii’s (and the U.S.’s) more shameful times, the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II.

A classic odd-couple tale slipped a couple of stiff Honolulu-sized drinks and drop-kicked into the ocean, Hang Loose involves an uncertain-of-himself straight-arrow (Kevin Wu, a.k.a. KevJumba, the popular Youtube comedian) and a confident, ever-handsome player (Dante Basco) who suddenly find themselves paired up and on the run from some tough-talking locals. Produced primarily for an online release and a few festival screenings, Hang Loose benefits greatly from the steady star power and charisma of Basco, whose easygoing charm turns what could be a stereotype of a character into someone likable, and a winning debut performance by Wu, whose slightly off-the-beat line readings and mannerisms showcase a comic intelligence and personality all too rare in independent film today. Like Yes, We’re Open, Hang Loose also showcases its setting—Hawaii, and specifically Honolulu—to great effect, and serves as a useful tonic to the usual outsider’s perspectives on the island.

“The festival is very supportive of local filmmaking and provides a unique, high-profile event to showcase locally produced films,” notes Kawamoto. The memorable screenings of The Untold Story: Internment of Japanese Americans in Hawai’i confirmed his message, selling out far before showtime and bringing in audience members—some of whom had either lived through the events in the film, or whose families were affected—whose emotional connection to the work resonated far after the screening. Though “merely” a documentary and with no stars or production budget to speak of, The Untold Story represents what HIFF and other regional film festivals stand for: a commitment to telling the often-unheard stories of the people and communities around them, and a desire to connect the power of “cinema” with the locale of the festival. “It was great to participate in the Guest Filmmaker Program and visit a media class in Kalihi, a predominantly local Filipino and more newly immigrated Micronesian community,” writes producer Theresa Navarro, a former Hawaii resident (and HIFF employee) who returned this year after co-producing Yes, We’re Open and Dave Boyle’s easy-going sequel to Surrogate Valentine, Daylight Savings. “I’m a big believer in the transformative power of storytelling across media, from music to food to film to art, and I shared my message with the students that if we don’t tell our stories, somebody else will do it for us.”