Back to selection

Back to selection

Stanley Kubrick’s Producer Jan Harlan on His Life in Film

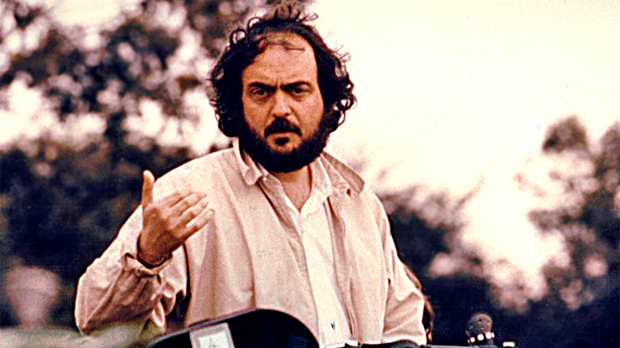

Stanley Kubrick on the set of Barry Lyndon

Stanley Kubrick on the set of Barry Lyndon If, like me, you’re a hardcore film geek who ranks Stanley Kubrick as your favorite director of all time, then Jan Harlan needs no introduction. At least that’s what I thought when I met Kubrick’s longtime producer (beginning with A Clockwork Orange — or rather the never-made Napoleon – right through to Eyes Wide Shut) this year at the Bermuda International Film Festival, where I’m on the international advisory board. Harlan was also Kubrick’s brother-in-law: his older sister Christiane was the director’s wife.

It was a simple twist of fate that I found myself filling in as a last-minute replacement on the Harlan-headed jury. (BIFF is Academy Award accredited for Live Action Short, with the winning short becoming eligible for Oscar consideration). As I grew to adore Kubrick’s right-hand man over five days of film-going, partying (the quick-witted septuagenarian still has the energy and exuberance of a teenager) and exchanging ideas about moving pictures and more, I soon came to a startling conclusion: Stanley Kubrick is perhaps the least interesting thing about this classy and endearing gentleman of the cinema.

Filmmaker followed up with the in-demand globetrotter post-fest to discuss everything from negotiating with the Belgian army for tanks, why Kubrick would have been infuriated by Room 237, and the great director’s biggest fear (unsurprisingly, mediocrity).

Filmmaker: I know you adamantly refuse to take credit for any aspect of artistry in Kubrick’s films, yet Kubrick often sought your opinions and suggestions when it came to choosing music. As a musician yourself I venture to guess you’re as knowledgeable about classical music as Kubrick was about films. Can you let us in on the discussions you often had, particularly during the making of A Clockwork Orange and 2001: A Space Odyssey?

Harlan: It is very simple. Kubrick was a powerful and very intelligent artist and filmmaker. I liked my role, which was to negotiate, plan and organize according to his wishes and needs. Recommending music was a sideline. You state that I adamantly refuse to take credit for any aspect of artistry in Kubrick’s films – I could not have expressed this better myself. You are right. This is not a sign of great humility on my part. I was very good in my role or, as I sometimes say, I was a good number two but would be a lousy number one. Bringing the Richard Strauss fanfare to him before I even worked with him was a coincidence. I knew it, he didn’t — so what? I know a lot of music, and he knew a million times more about other things I had never even heard about.

Filmmaker: At the risk of making you really, really angry with me for asking this question, how would Kubrick have reacted to Room 237? And more importantly, why wouldn’t he have just laughed it off as mere silliness unworthy of response?

Harlan: This so-called documentary would not have been made while Kubrick was alive, which says it all. He would not have laughed it off since it repeated the other grotesque story about filming a fake moon landing, invented by ARTE France as a hoax in a TV program also made after his death. The latter refers to 1969 and The Shining was made in 1979. Do I say more? Saying that people waiting in the hotel lobby with suitcases was a reference to the Holocaust is both an insult to Stanley and to the victims of this low point in human history. Endless drawings to prove that the large rooms could never be in the hotel we see from the outside — it takes a genius to figure this out? It’s a ghost film! Almost nothing makes any sense.

Filmmaker: I’ll never forget what one of my film criticism mentors, Matt Zoller Seitz, once told me – that the first thing he does when reviewing something is to look in the mirror and ask, what is it about me that’s causing me to react this way? In that spirit, could you talk a bit about your upbringing (particularly as a German born in the ’30s) and how that affects your view of, and sensitivity towards, certain subjects and films?

Harlan: We are all formed by our upbringing and can’t be objective, but I have never self-analyzed myself as a German born in 1937. I am what I am. I am as German as they come. Although I left Germany and prepared for my earlier profession in Zurich and Vienna as well, I emigrated to the U.S. in 1962 as a green card holder (after swearing at the US embassy that I wasn’t — or have ever been — a member of the communist party or homosexual). I loved New York, walked the streets for four weeks with open eyes and mouth – a new, different and exciting world. I bridged my Vienna years with some pride by visiting the old Metropolitan Opera (what would they do without the Germans and Italians?) and seeing a lot of European art at the Metropolitan Museum. I then started to work: jobs in my field were easy to get, so I could pick and choose. I was thrown out of shops sometimes because of my accent, but I had no problem with that since I was sympathetic towards the victims of the Nazis and made lots of friends in that community.

Filmmaker: You’ve met a lot of incredible people and had amazing experiences as a result of being Kubrick’s producer for 30 years. (Meeting Chaplin at the Academy Awards, for example, seems pretty damn exciting.) What do you consider the most memorable, something life-changing that altered your viewpoint or rocked your world?

Harlan: The amazing people you are referring to were just that – amazing. I learned most from people who were less amazing but very smart and new to me, from the Warner Brothers executives and the lawyers I had to deal with in Los Angeles. During my work I met such different people since the films had such different topics.

I remember well an officer of the Belgian army who controlled three completely outdated U.S. tanks from the Vietnam period. I wanted to hire these, but hiring out tanks was simply not in their books. After long chats we ended the negotiations with him simply saying, “Just bring them back.” In my little life he was an amazing man. The tanks served us so well, and we squeezed these like a lemon to create “Vietnam in England” for Full Metal Jacket.

Filmmaker: You mentioned during the talk you gave at Bermuda that Kubrick’s biggest fear was mediocrity. New York Times critic Manohla Dargis has theorized that the abundance of mediocre films in the market is actually doing a disservice to the gems, making it harder and harder for critics to dig through the morass to find them. With all the films out there nowadays, do you think Kubrick’s earliest work would have even gotten Warner Brothers’ attention in the first place?

Harlan: Most writings disappear, most music, most paintings, and certainly most works by architects – all gone within a few decades. But what is truly great remains and will be a reference for future generations. Film as an artistic expression is new, barely a hundred years old. Again, most films disappear quickly, but the great masterpieces from Eisenstein, Orson Welles, Ingmar Bergman, Edgar Reitz or Stanley Kubrick will remain and will serve future generations to look into the second half of the 20th century. I named just a few – there are more – every generation produces a number of great artists and great art.

Kubrick didn’t want to make a film that disappears, and I am so glad that he succeeded. And the people working with him knew that they had the chance to be associated with a film that will last, looking back at Paths of Glory, Lolita, Dr. Strangelove, 2001: A Space Odyssey, and so on. Eyes Wide Shut was only recognized in the Latin world and in Japan, but I predict that this film will have a great renaissance for those not yet born. As to the studio system, I can only say that Warner Brothers supported him completely since 1970. Stanley worked within the studio system. CEOs like Terry Semel were superb executives and judged Stanley well, took the risks, and often won.