Back to selection

Back to selection

Shutter Angles

Conversations with DPs, directors and below-the-line crew by Matt Mulcahey

“You Don’t Light with Your Meter, You Light with Your Heart”: Gotham DP Crescenzo Notarile

Gotham

Gotham Fitting an interview into a cinematographer’s schedule can be daunting, especially a DP working on a television show that shoots nine months out of the year. You often end up chatting after a long shoot day or during a mid-day tech scout break. Orm in the case of Gotham cinematographer Crescenzo Notarile, you talk a few hours before their name is read at the 68th Primetime Creative Arts Emmy Awards. Notarile earned his Emmy nomination for his work on Gotham, Fox’s origin story tracing the early days of cop Jim Gordon and the various heroes and villains that reside in the titular city. The show’s third season bows tonight.

Notarile was generous enough to take a few minutes out of his Emmy prep to chat with Filmmaker about Gotham’s signature style, the challenges of hiding lights from the show’s wide-angle lenses, and what he learned from working on Sergio Leone’s Once Upon a Time in America.

Filmmaker: So the Creative Arts Emmys are today?

Notarile: Yeah, they’re in a couple of hours from now. I’m trying to get ready. I’ve got a lot on my mind and I’ve got a lot of energy inside of me. I came off of a night shoot yesterday and I just flew in (to Los Angeles) so you can imagine all of the emotions I’m going through right now.

Filmmaker: You’re nominated for the episode “Azrael” from season two of Gotham. So you are judged basically on only one episode of the show?

Notarile: I have to choose one continuous excerpt that’s around four or five minutes long, I can’t remember the exact length. When you’ve got 11 episodes that are 44 minutes each and you’ve got to pick out just a few continuous minutes to be judged by your peers, it’s a torturous, torturous procedure.

Filmmaker: What excerpt from “Azrael” did you end up going with?

Notarile: This particular year I chose something that was very unconventional and I guess [my nomination] is a testament to my choice. I chose something that was very dark and very difficult. The scene that I chose called for a blackout in one of our major sets, the GCPD [Gotham City Police Department], which is our largest, most iconic set. You walk into that set and it looks like a grand cathedral. It takes up the space of an entire soundstage. All the practicals, the sconces, the desk lamps, all the ambient lighting, etc. was all out because of this blackout in the scene. It’s hard because the audience has to feel that you are in total darkness, but you have to be able to see the information. There’s a very fine line there. If all the lights are out, you ask yourself, “Okay, what motivates the lighting?” And the only thing I had working for me was moonlight coming through the windows. So I had to surgically and precisely create beams of moonlight and pools of moonlight, all within this very intricate fight sequence where Azrael is rappelling and leaping up walls and across ceilings. I said to myself, “If anyone is going to get what I’m doing here and if anyone is going to appreciate how difficult it is to light something like this, it’s my peers.” And they are the ones that chose me for the nomination. I call this particular age of television that we’re in The Platinum Age of Television and I’m so honored to be part of that in a time when the bar is as high as it’s ever been.

Filmmaker: Before we dig deeper into Gotham, I want to ask about a couple of other projects you were a part of, starting with your time on Sergio Leone’s Once Upon a Time in America.

Notarile: That was the very first film where I stepped up to become a camera operator. I started off as an assistant cameraman and two weeks into the film they added another camera and I got bumped up. I was only supposed to be bumped up for a few days to operate the third camera. Cut to nine months later and I’m still operating on the movie.

Filmmaker: Were you an admirer of Leone and cinematographer Tonino Delli Colli?

Notarile: Absolutely. I bugged the production manager Fred Caruso to get on that movie. I called him every day. I was selling myself up and down, left and right, for weeks and weeks. I was so anxious to get on a film like that, not only because of the size and the caliber of the film but because I was a fan of Sergio Leone and Tonino Delli Colli. When I was hired it was like Christmas ten times over for me.

Filmmaker: Did you take any specific lessons away from working with Delli Colli?

Notarile: I did. I was stunned that Tonino had a $25 reflective Sekonic light meter. It was the size of a matchbook. It was so small. What I took home from that experience — and he and I had major conversations about this, he turned out to be a mentor of mine — was that when you light, you don’t light with your meter, you light with your heart. I used to watch him work and he never, ever pulled out his light meter until the very, very end, when the principal actors came out and we were ready to roll. Then he would just pull it out nonchalantly and get a quick light reading and call it to the camera assistants. I never once saw him lighting with a light meter. Now when I light I try to go more with my gut and my heart. When you reach a certain point in your career, all the technicality should be second nature to you. It should be like tying your shoes. What separates the men from the boys, in my opinion, is taking that one step further and going with your heart, going with the emotion of what that story is about and trying to create something for the audience to feel through your lighting.

Filmmaker: You also shot some of the Michael Jackson film Moonwalker (1988).

Notarile: That was an extraordinary experience. I was one of the few cameraman at that time that was known for their music video work who was traveling all over the world working with the biggest bands doing iconic music videos. That’s how I learned my craft, to be honest with you, was through my music videos, because of all the exploration and the freedom you have on a music video set.

What I walked away from that one with was just the experience of working with Michael Jackson. In my opinion he truly was a genius. He was truly a prodigy as an entertainer and a musician. I was very, very inspired watching him work because of his precision. He was a perfectionist and I gained a tremendous amount of respect for him as an artist. He was very soft spoken, very introverted, very shy, but when he got on stage he was a totally different person.

Filmmaker: When you’re coming onto a show like Gotham that’s in its second season, how do you balance staying true to the look and style that’s been established while still injecting some of your own personality?

Notarile: You need to go with the guidelines, you need to stay within the parameters, but you’re also being hired for your particular sensibility. Everyone has a different thumbprint. Everyone has a different way of seeing things. It’s a very subjective medium. I can light something and you can get twenty different people to look at it and they’ll give you twenty different opinions. What is a warm light to me may be entirely different from another DP. Does warm mean more orange? More straw? It’s very subjective.

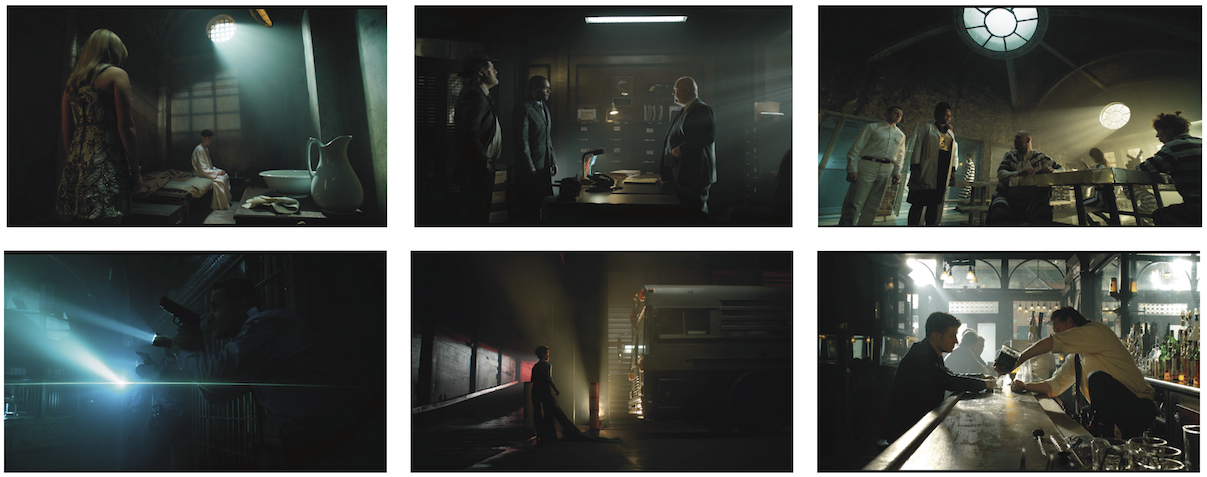

This particular genre that Gotham falls into is extraordinary because it gives the cinematographer an opportunity to think outside of the box. We’re creating our own world. We’re not doing Law & Order where things are very docu-style and very real. With Gotham, you are able to think surrealistically. Before I took this show I wasn’t necessarily a comic book fan, but I bought a few giant volumes of graphic novels, especially Batman, and I submerged myself in them and what I noticed mostly was the composition of the frames. They were very exaggerated, very pronounced — high angles looking down, low angles looking up, close-ups of the characters that exaggerated their faces like a fish-eye wide-angle lens. So I tried to bring those elements to the table a little more than what the show had been doing.

Filmmaker: It’s an Alexa show?

Notarile: Yes, our A and B cameras shoot Arri Alexa studio cameras with old, vintage Panavision lenses. All of our shooting is with prime lenses — no zoom lenses. We also shoot our show mostly with wide-angle lenses, which is unique. For instance the show I did prior to Gotham was CSI and that was the total antithesis in philosophy. When I did my close-ups on CSI they were on a 150mm to 250mm telephoto lenses. But on Gotham my close-ups are anywhere between a 17mm to a 28mm. So instead of me being 35 or 40 feet away from the subject with long telephoto lenses, I’m literally 1 to 2 feet away from the subject shooting close-ups and I think that’s what gives the show some of its personality.

Filmmaker: A big part of the show’s personality is also the mixed color temperatures. On thing you specifically like to do is key with one temp and then use a different temp for the kicker.

Notarile: I’m a big fan of that. I personally like kicker lights or edge lights, because when I have an edge light it chisels the subject from the background and that’s one way of making the subject really pop out when you’re using wide-angle lenses. When I am key lighting a face, I like seeing the flesh tones more on the golden side, so I’ll use a little warm gel on the key light and I’ll oppose that with a cool light for the edge light. I will always put my edge light on the fill side just to edge that jawbone and cheek so that they don’t blend into the background. I drive my gaffer crazy trying to get those edge lights in, because when you’re constantly working with 10mm and 14mm lenses on every single shot, you see everything in the background. There’s no room to hide any lights. We’re always trying to hide lights behind furniture, behind columns, behind whatever is on the set. Sometimes I will bring in a chair that has nothing to do with the set just so I can hide a light behind it.

Filmmaker: Are those mixed color temperatures easier to achieve now with all the LEDs that allow you to dial in any hue you’d like?

Notarile: Well, you still have to know where to place that light. You still have to know how to shape that light. You still have to know what color to put on. Technology is just a tool. It doesn’t make anything easier, per se.

Filmmaker: Maybe easier isn’t the right word. How about faster?

Notarile: I personally love LEDs and, yes, they do make things faster. With one quick turn of a dial you can change the color temperature of a light versus telling your gaffer to change the gel on the light and then you see an army of guys coming in with ladders, brining down the lights, cutting the gels, clipping them on, hoisting the lights back up, etc. So yes, LEDs do make it faster.

Filmmaker: Another signature of the show is the shafts of light that stream into the sets. What’s the key to achieving that effect?

Notarile: There are two keys – big lights and smoke. We use three different big guns – 12K MoleBeams, 7K Xenons, and 10K Beam Projectors. But without the smoke, you’re not going to have that beam of light. We’re constantly working in a cloud of smoke. It’s interesting because when you look at an HD monitor you can hardly feel the smoke, but on the set you can hardly see your hand in front of your face it’s so cloudy. Nobody’s particularly fond of that, including myself. I have asthma, and believe me using smoke is the last thing I want to do, but as the expression goes you have to have pain for your art.

Filmmaker: When you have that much smoke, do you have to watch that your blacks don’t get lifted too much?

Notarile: Absolutely. When you have that much smoke it deteriorates the contrast. The blacks become milky and gray. I personally love high contrast. I love when the blacks go inky black. Working with my DIT on the set, who’s side by side with me, I will manipulate my settings to increase the blacks in certain areas. I’m constantly on the backs of my special effects department with the smoke because the smoke affects not only the contrast of my photography but also the exposure. So the use of smoke is an incredibly important tool for us on the show, but there’s a fine line there.

Filmmaker: Lastly, I’d like to get an idea of what goes into a wide shot like the one above. Is any of that background a digital matte painting?

Notarile: That is 100 percent practical. We had a rooftop in midtown Manhattan that we chose because it had Old World, Gothic-like buildings that felt very Gotham-esque. During my prep I had to figure out what time it gets dark and how long it was going to take me to light. I had to figure out how to take advantage of my pre-rig and my pre-lighting so that when I walked on the set I could hopefully just cross the t’s and dot the i’s.

There’s only a certain time of night where all the windows and all the practical lighting that you see in the apartments and the architectural lighting of buildings are on. Between 1130pm and 2 am, everything just shuts down and all of a sudden you’re doing one shot where all the practical lights are on and then you break for lunch and you come back and all the lights are off and you can’t match it. A lot of times when I’m on locations like this, if there’s a specific spot that I know I’m going to be looking at most of the evening for our master shot, I’ll ask the location manager to go to those apartments and ask [the people who live there] to leave their lights on in those windows so I can feel a little eye candy in the background. Otherwise to me it does look flat like a backdrop. Also you’ll notice that those lights have a little streak to them, a little flare.

Filmmaker: It’s almost like the horizontal flare you get with anamorphic lenses.

Notarile: Exactly. I used a streak filter for that particular scene for that purpose. I thought it gave a little extra personality to it.