Back to selection

Back to selection

Festival Cinematography Notes: Of Sundance, Berlin and the Canon 5D

Blogging from last year’s Sundance I wrote that “if I could give an award to the camera delivering the most impact on screen at Sundance 2011, it would go to RED One.”

That was then. In the 12 months since, ARRI’s Alexa has all but conquered TV series production in the U.S., and now you can add a dozen low-budget indie films at Sundance too, like the bittersweet romcom Celeste and Jesse Forever, starring Rashida Jones and Andy Samberg and photographed by David Lanzenberg.

Sony’s new budget-friendly F3 made a splash at Sundance as well, responsible for Spike Lee’s Red Hook Summer, shot by Kerwin Devonish, and Colin Trevorrow’s puckish Safety Not Guaranteed, shot by Benjamin Kasulke, which won the Waldo Salt Screenwriting Award. Trevorrow said his 2.40 aspect ratio was the result of vintage Panavision lenses used to achieve what the director called “a 1970’s Hal Ashby look.”

For me, however, the camera that cast the longest shadow at this year’s Sundance was the Canon EOS 5D Mark II, whether or not it was actually used. Let me explain.

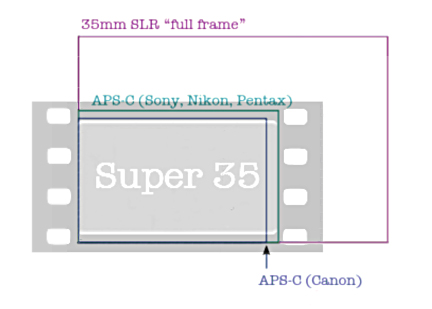

Nearly all large single-sensor motion picture cameras today, including those responsible for Sundance 2012 premieres, use Super 35-sized sensors, including Alexas, RED Ones, Sony F35s, F3s, FS-100s, and Canon 7Ds. The major exception is the Canon 5D, which uses a significantly larger sensor.

Super 35 matches the original 18 x 24 mm “full” camera aperture used to expose 4-perf 35mm film in the silent era. As it happens, the APS-C sensor found in some DSLRs is also a match—why Canon’s 7D makes the list.

This original 35mm motion picture format devised by Eastman and Edison 120 years ago is the classic one around which most motion picture camera and lens technology developed, as well as technique and cinematic language.

35mm motion picture film also gave rise to two still formats: a 4-perf frame (same as motion pictures) and a larger 8-perf frame that traveled sideways. The Simplex still camera of 1914, for example, snapped both formats.

8-perf eventually prevailed for stills because small 35mm negatives had to be enlarged for prints, and the larger negative yielded a superior result. The most famous 8-perf 35mm still camera was the Leica of 1925.

The reason I’m digging into this history is that until the arrival of the Canon 5D with a sensor the size of 8-perf 35mm, this larger, horizontal 8-perf “full frame” (as still photographers know it) was absent from the big screen.

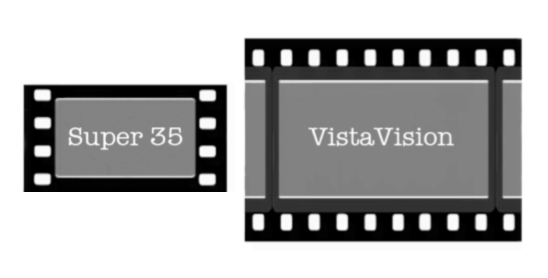

Not that sideways 8-perf hadn’t also been tried in motion pictures. Introduced as VistaVision in the early 1950s, it lasted barely a decade as a production format. It required cameras with large butterfly-wing magazines, awkward to move and twice as noisy, consuming double the footage of 4-perf. Special horizontal projectors were needed to screen the results natively.

8-perf sized images, called “full frame” in the worlds of the SLR and DSLR (purple outline in illustration above), require lenses with a greater image coverage than 4-perf Super 35. This translates into longer focal-length lenses for the same horizontal angle of view. Which means less depth of field.

Less depth of field is, of course, the battle cry of those who champion the images from full frame DSLRs like the Canon 5D as “more cinematic.”

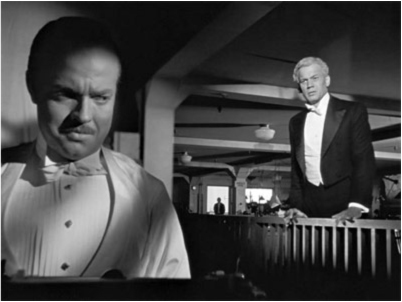

Much of this is claptrap. The shallower focus of larger 8-perf formats has never been central to the vocabulary of 35mm cinematography, any more than the even shallower focus of medium format photography. I often cite the example of Gregg Toland’s deep focus in Citizen Kane to rebut the notion that shallow depth of field per se spells cinematic.

(Anamorphic cinematography does use an optical squeeze to shoe-horn a VistaVision-sized image into a 35mm frame, one with separate horizontal and vertical depths of field. This is the look—a complex one—I suspect Canon 5D enthusiasts truly aspire to emulate.)

In any case, the worldwide low-budget juggernaut that is the Canon 5D—a large sensor camera for the price of a prosumer camcorder, capable of stunningly artful images—cannot be denied. It has become the Jolly Roger of a new generation of filmmakers, a declaration of independence from the costs, if not also craft, of large professional cameras.

At Sundance, at least one feature was shot entirely on the Canon 5D, Quentin Dupieux’s WRONG, in the World Cinema Dramatic Competition. Equal parts minimalist and absurdist, Wrong is the story of a sad sack who wakes up one morning to find his beloved dog, Paul, missing. The French Dupieux, both writer and cinematographer, turned his 5D into a literal caméra-stylo.

Over in the U.S. Documentary Competition, Director and D.P. Matthew Akers resorted to use of a Canon 5D to solve a problem during filming of Marina Abramovic: The Artist is Present. Initially shot vérité-style, using a Varicam to follow Abramovic coaching performers on the grounds of her rural Hudson Valley redoubt for her upcoming MoMA exhibition, Akers found he needed a more compact solution when filming Abramovic as she sat for hours during her performance in MoMA’s packed Marron Atrium. Restricted to the corners of the Atrium, Akers employed a 5D to conserve space while obtaining tight shots of Abramovic with a long lens. He said he discovered the flattened, narrow-focus perspective to be the perfect complement to his subject.

Phil Cox’s uplifting 3-minute short Hilary’s Straws, which played before a Documentary Competition feature, also showcases hallmarks of the Canon 5D. Shallow-focus close-ups with sensitive editing and poignant voiceover blend perfectly to convince you that Hilary, paralyzed, can “fly” across the English Channel in her modified sailboat. (http://focusforwardfilms.com/films/2/hilarys-straws)

But more than actual use of the Canon 5D at Sundance, I encountered what I believe to be its influence. In former documentary filmmaker James Marsh’s Shadowdancer, shot in 35mm Fujicolor by DP Rob Hardy, there’s an early interrogation scene in which would-be London Underground bomber Colette, an IRA operative, is grilled by an MI5 officer named Mac. In a series of back and forth close-ups between the two, depth of field is so thin that ears and nose are not in focus at the same time. The 5D look is unmistakable.

One snowy Sundance night I ran into a local filmmaker, Steve Olpin, a friend who has used several video formats since DV to shoot both documentary and extreme sports. He told me he’s switched to the 5D, and that despite the ergonomic drawbacks, for him it’s the simplest shooting ever, he just presses a button. He says he exploits the difficulty in controlling focus as a stylistic element. “Shooting on the balls of your feet” he calls the telltale 5D look of rocking in and out of focus.

I don’t use DSLRs much myself. I dislike the accessorizing. I miss the ability to dig into color matrixes, add knee points and slopes, select gammas—but that’s exactly what Steve likes about the 5D, and truth is, simply pressing a button is closer to shooting with a film camera. Or, for that matter, an iPhone.

Speaking of film cameras, reps of ARRI remarked over dinner that they’d seen several films at Sundance shot on DSLRs and that they looked great; and anyway, it’s the story that counts most. (Nothing in this business is rarer or more gratifying than candor.)

I juxtapose these anecdotes because they resonate. We’re surfing a Cambrian explosion of new forms of motion-picture cameras, as the old order crumbles beneath us. During Sundance, for instance, Kodak filed for Chapter 11 protection. During February’s Berlinale, New York lost another film lab (lab operations at Technicolor/Postworks were shut down and moved to Deluxe). New technology begets new technique, which begets new styles and new opportunities, which is terribly exciting.

When I saw the opening scenes of Benh Zeitlin’s smash Sundance hit, Beasts of the Southern Wild, shot by Ben Richardson, I thought, “Canon 5D”—even though I knew it was shot in Super 16. The opening scenes include a wild, raucous, late-night party outdoors, with drinking, horseplay and reckless fireworks. At some point 6-year-old Hushpuppy runs around with sparklers in each hand. She drifts in and out of focus, mostly out, which might or might not have been a conscious choice while shooting. But its inclusion in editing was a choice, and it’s one of the strongest visuals in the film.

The 5D came to mind because we see so much casual out-of-focus imagery in student films, music videos, and commercials these days—which I attribute to the aforementioned juggernaut. Like fast cutting, drifting in and out of focus is a consciously arty technique that wears thin fast, possibly because it obscures more than it reveals. To Zeitlin’s and Richardson’s credit, out-of-focus shots in Beasts are sustained, not cut away from, and grow more effective because of it.

So… while out-of-focus photography is nothing new, I think the 5D is responsible for its newfound cachet in motion picture images. At least at Sundance.

In February I participated as an “expert” in the Berlin Talent Campus, a six-day section of the Berlinale devoted each year to a lucky 350 young filmmakers from around the world.

A microcosm of the larger Berlinale, the Talent Campus provides talks and workshops by the likes of Mike Leigh and Keanu Reeves. For instance, I attended a memorable talk by costume designer Sandy Powell and another by the great DP Ed Lachman, whose wry anecdotes of working with Godard, Wenders, Hertzog, Haynes, Soderbergh, etc. were priceless.

There’s even a Talent Press program for hands-on training of young film journalists and critics. Which is why the Berlinale is not only a world showcase for film, but a world springboard for film industry talent. But I digress.

I tried to see as many films as possible at the Berlinale, since many will not find distribution in the U.S. As the Berlinale concluded, I made a list of the films I’d seen and realized something interesting.

With the exception of Brian Cassidy’s and Melanie Shatzky’s Francine, featuring Melissa Leo as a withdrawn woman recently released from prison, shot by Cassidy in gritty, underlit HD in 2.40 aspect ratio, with what could have been a DSLR (I should have asked), all of the dramatic films I saw at Berlin were conventional in the sense of impeccable production values, slick cinematography, and comfortable finances. (I’m speculating about the last one, but you can always kind of tell.)

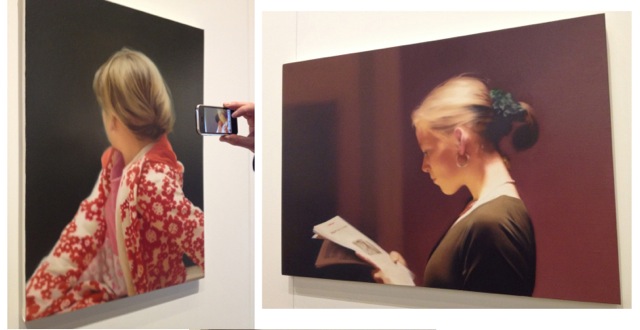

In other words, the opposite of gritty or ragged. No fuzzy shots or low-cost camcorders in the mix. Nothing distressed or textured in the sense of the medium. I found this particularly ironic in light of the nearby retrospective of the work of the great German painter Gerhard Richter in the Neue Nationalgalerie, about a five minute walk from the Berlinale’s main drag. Richter is known for his Blur paintings of the 1960s and 1970s, in which an image derived from a photograph is painted in black and white, then blurred by Richter to the edge of recognition.

While in Berlin I hung out with scrappy local filmmakers, friends of mine, who struggle to make independent documentaries. One, a veteran DP, I was surprised to learn is now using a Canon 5D instead of an HDCAM. I picked up the same vibe from young Talent Campus filmmakers: the American indie notion of starting a film project without a green light, without funding in place, using cheap digital tools, seems to be spreading around the world.

But it’s equally true that in Europe and elsewhere, where there exists state support for the arts and filmmaking in particular, where filmmaking is considered a real profession, that availability of money from commissioning editors and various film funds shapes the filmmaking that results. To be a producer in Germany, for instance, requires a substantial bank account and official sanction. Buying a camcorder and Final Cut Pro and calling yourself a filmmaker doesn’t cut it, as far as funding and recognition go.

An alien universe to an American, post Reagan. Perhaps one in which fewer chances are taken though.

Original photos and illustrations by David Leitner.