Back to selection

Back to selection

“My Approach is More Novelistic than Journalistic”: Director Frederick Wiseman on His Oscar-Shortlisted Doc, Ex Libris: The New York Public Library

Ex Libris: New York Public Library

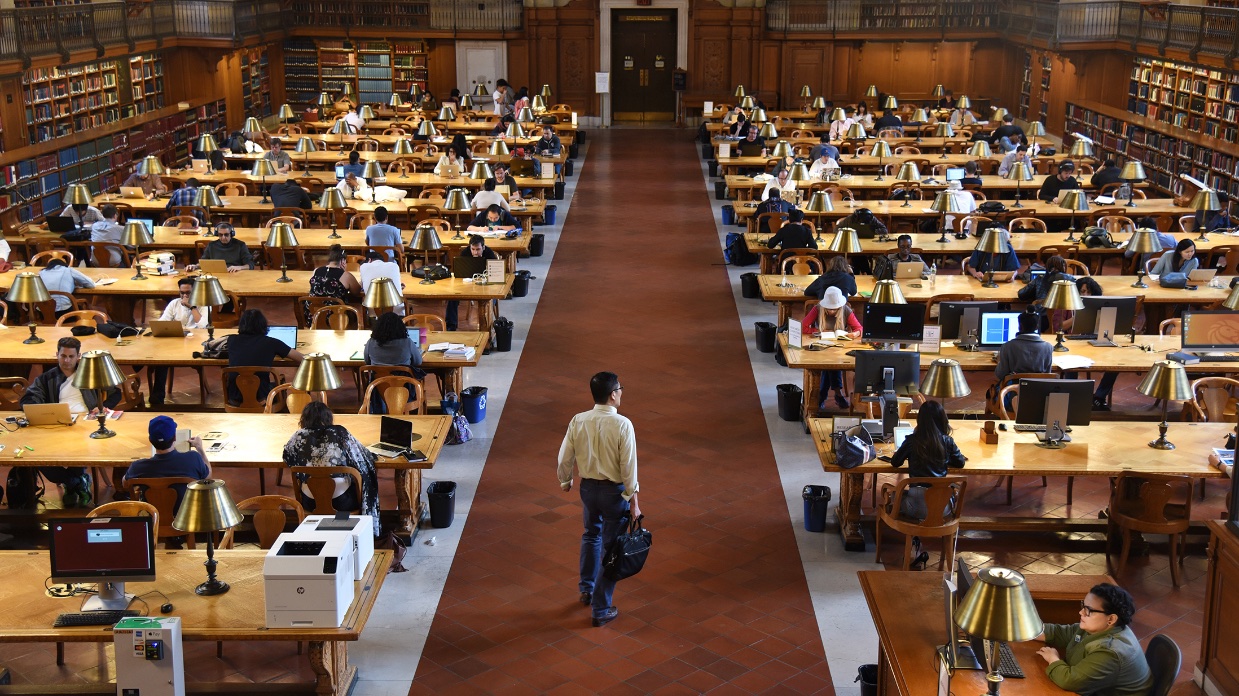

Ex Libris: New York Public Library Now 87, Frederick Wiseman is showing no signs of slowing down. His most recent documentary Ex Libris: The New York Public Library, which gives an inside look at the esteemed institution, has been shortlisted for the Academy Award for Best Documentary. Staying true to the filmmaker’s distinctive style of organic, no-fuss lensing, with subtle opinions about his subject matter teased out through his editorial process, Wiseman assuredly conveys in this latest work, via 197 minutes of filmic snapshots, the rich intellectual life offered — and symbolized by — the Library and its offering of community events and talks with figures like Patti Smith, Elvis Costello and Richard Dawkins. Ex Libris steers clear of underlying politics, such as the controversy surrounding the abandoned Central Library Plan, and instead beautifully shines a light on its members of all classes and ethnicities that attend its spattering of 88 local branches and four research centers.

At this year’s Venice Film Festival, Ex Libris won the FIPRESCI Prize and the Fair Play Cinema Award, and in November, Wiseman received the Critics’ Choice Best Director Award, alongside Evgeny Afineevsky for Cries from Syria. At last month’s Camerimage Film Festival, where the below interview took place, Wiseman was spotlighted with the Camerimage Award for Outstanding Achievements in Documentary Filmmaking. In his acceptance speech, there, Wiseman was vocal in his alarm over the current presidential administration and its threat to the First Amendment, an American right that he greatly values in allowing him to “go to all kinds of places” in his filmmaking. “Freedom of speech is threatened by a fascist,” he said.

Below, the revered documentarian spoke to Filmmaker further about politics, his decision to focus on the New York Public Library, and his fearless determination to keep working and “avoid the grim reaper.”

Filmmaker: You mentioned in the opening ceremony of this year’s Camerimage International Film Festival that the First Amendment is under threat with President Trump and the current U.S. government. Do you think the First Amendment could be taken from U.S. citizens?

Wiseman: It can be taken from us in the way the courts interpret it. These judges are being appointed based on their political views, and the ones he has appointed so far are extremely conservative. The fear is that he [President Trump] has this Joseph Goebbels-like technique saying newspapers like The Washington Post and The New York Times are “fake news.” He has picked up from Goebbels (though he probably doesn’t know who Goebbels is) the notion of a big lie repeated over and over again, and that is what he is doing with “fake news” in the effort to discredit legitimate news sources and to magnify the importance of media organisations like Fox News and Breitbart, which are run by his avid supporters. So what is in play is the ability of news organizations to report accurately on what is going on. He is undermining the idea that there can be a consensus on what facts are. And that’s extremely dangerous for a civil democratic society.

Filmmaker: Do you have an interest in highlighting situations such as the threat to America’s freedom of speech in your upcoming films to help build awareness and subsequent change?

Wiseman: The whole notion of social change is a complicated question and I am not sure one can measure the effect of any one work on social change. I think if people want to affect social change they should not be filmmakers, they should become politicians.

Filmmaker: But didn’t your film Titicut Follies (1967), that highlighted the inhumane treatment of inmates at the Massachusetts Correctional Institution at Bridgewater, have an impact on social change?

Wiseman: I think it would be pretentious of me to say Titicut Follies was responsible for the changes at the state prison [for the criminally insane] that was called Bridgewater. Over time, yes, there were changes: a new building was constructed ten to 15 years after I made the movie, inmates who had been there for many years had been discharged to nursing homes, and its population went from 900 to 350. But for me to claim the film is responsible for that would be totally pretentious because Massachusetts Medical Society, Massachusetts Bar Association and various newspapers were interested. Also, within Bridgewater’s new building, the staff have improved over time; but then in the last five or ten years it’s become bad again.

Filmmaker: Would you have an interest in highlighting a political institution in an upcoming film?

Wiseman: I did the Idaho State Legislature [in State Legislature], where I had complete access to whatever was going on. But on the national level, I don’t think I would get access to the really interesting material. I might get access to the public aspect like press conferences and speeches. But I might not get access to the planning sessions, because they might be fearful whatever they are planning would get revealed to their opponent. I think the only way you could do that is if you promise to wait and release the movie in 50 years. And since I won’t be around in 50 years…

Filmmaker: How did you decide on The New York Public Library as your latest institution of focus?

Wiseman: I woke up one morning, around the time I was finishing In Jackson Heights. I had the need to start another project, and it occurred me to I had never placed focus on a library. I didn’t know anything about the New York Public Library other than it’s one of the great libraries of the world. The last time I had been in the New York Public Library was 45 years ago. I went there as a tourist. And the last time I spent time in a library I was at graduate school. I had no idea the New York Public Library offered such a wide variety of programs and services in the community through their various branches.

Filmmaker: How long did it take you to get permission to film at the New York Public Library?

Wiseman: I got in touch with Tony Marx, who is the head of the library, and he said okay right away. And then I started shooting a few months later. I spent 12 weeks shooting [in 2015] and a year editing. I guess they sent out a notice to its members that I would be filming, and people cooperated. The staff liked the idea of a movie being made. Permission is never a problem. It’s extremely rare anybody says no to being filmed. It didn’t happen at all in this movie, and it rarely happens. Generally, people like the idea that people are interested in their views. But I don’t do interviews — I am not asking anybody anything other than to let me film. Interviews are an artificial situation.

Filmmaker: How did you decide which of the branches of the New York Public Library to film in?

Wiseman: A lot of sequences are in the main library [on Fifth Avenue and 42nd St.] because there were a lot of meetings there, and the top administration is based there. For the other branches — there are around 90 altogether. I shot in 17 branches, and I think there were 13 in the film. It was dictated by whatever activities were going on. I heard there was a job fair in the Bronx library one day, and then I read in a bulletin there was an event on sign language. I was interested in that because I had made a film [Deaf] about the School for the Deaf [at the Alabama Institute]. It was just about things we stumbled upon that looked interesting.

Filmmaker: Some people have wondered why you didn’t film in the historic reading rooms, the Rose Main Reading Room and the Bill Blass Public Catalog Room?

Wiseman: They were closed — they were under construction.

Filmmaker: You are known for filming an extensive amount of footage. How much footage did you have for this film, and how did you then organise the material?

Wiseman: We had 150 hours of footage. You can’t let yourself get overwhelmed by that. For my film At Berkeley, I had over 250 hours of rushes because professors like to talk. It’s just a case of sitting there and doing it. I’ve been doing this a long time — I know if I sit there long enough I’ll find a film. Sometimes I use a notebook where I write down the order [of the shots].

Filmmaker: How many people do you work with when filming?

Wiseman: It’s a crew of three. It’s always been like that. I direct and do the sound, I work with a cameraman and then a third person carries the equipment. And no lights. You just hang around, that’s the basic technique.

Filmmaker: You capture moments such as people sitting at tables scanning their smart phones or ordering portable hot-spot devices to, as the librarian fears, potentially binge on Netflix series. Yet, few shots actually showcase physical books. Was that intentional? Did you know there would be this digital focus at the library?

Wiseman: No, I really had no idea what went on in the New York Public Library. I never know ahead of filming what the central themes will be. I just start filming. And because the New York Public Library caters to everyone through its wide variety of community events, we were able to film different classes, races and ethnicities. It’s a film about New York. But my approach is more novelistic rather than journalistic. I try to resist ideological explanations. All of my films have a point of view which emerges from the editing — the structure becomes the expression of my point of view.

Filmmaker: At what point do you start editing?

Wiseman: While I’m filming, I just about have time to watch the rushes. I don’t start editing until we have finished filming.

Filmmaker: Can you explain how you determine a film’s “dramatic structure,” as you have referred to it, or its central themes when editing?

Wiseman: It’s my imagination in play against the 150 hours of rushes. My job as an editor is to impose a form on the chaos of the rushes. And the form is what the film is. I have to try and think my way through the material. Each sequence I am looking at I have to ask myself the question, “What is going on?” I have to delude myself into thinking I understand what is going on in order to decide whether or not I want to use that sequence, to figure out how I can compress it into a usable form, and where I will best place it in the structure. The analysis goes along two tracks. There is the literal track: who is saying what to whom, what are the gestures, what kind of clothes people are wearing. And then there’s the abstract track: what general ideas are suggested by the specific literal encounters. So the real movie is in a relationship between the literal and the abstract.

Filmmaker: Music plays an important role in many of the scenes, such as the music that is emanating from people’s computers or phones. Did you separately record sound? I know you are averse to using score.

Wiseman: The music is recorded as part of the sound that exists at the places in the film. For my kind of filmmaking, it would be phony to add score. I am representing that what you see in the movie is what actually took place. If I add music, it’s something I added.

Filmmaker: With Ex Libris: The New York Public Library shedding light on the continued emergence of digital media, how have you as a filmmaker dealt with the new digital technologies?

Wiseman: I’ve had to learn digital editing a little bit. In terms of shooting, it’s exactly the same. We use a variety of cameras: Sony PMW-F55, Arri Amira and RED. We tend to use the Sony F55 more often. But the design of [film cameras] such as the Aaton and the Eclair was really great because it was designed for handheld work, which is primarily how we film.

Filmmaker: Given the choice, would you shoot on film or digital?

Wiseman: I would still shoot on film. I edited that way for years, and I much prefer editing on film. And I still like the look of film. What we do now in the color grade is to give the images a filmic look. But it’s impossible to shoot on film now because labs don’t have daily baths, some are going out of business, and you have to order the negative way in advance. Production wise, it is more expensive to shoot on film, but overall the cost of shooting on film is not that much different. Ultimately, post production costs are greater digitally because color grading is so expensive.

Filmmaker: There is a new Kodak film lab that opened in New York. Would you be interested in working with them?

Wiseman: I didn’t know that. If they process 16mm film, I would be very interested in contacting them.

Filmmaker: How have you seen funding change for documentaries over the span of your career?

Wiseman: PBS has been a regular funder for me (except for my first two films, Titicut Follies and High School. PBS didn’t even exist then). The don’t contribute a lot — around 15-20% of the budget. It’s important because in the beginning, it gives certainty to other funders that the film will be made and shown, whether on television and more often theatrically as PBS likes that it establishes the reputation of the film and brings built-in publicity when it’s shown on television.

So it’s always a combination of PBS, occasionally ITVS, and The Ford Foundation, who over the years has been one of my principal sponsors. From 1971 to 1981, I had two five-year contracts with them that allowed me to make one film a year. So for ten years I didn’t have to raise money, I just had to call up Channel 13 and say “Juvenile Court” and they’d send me half the money, and I’d get the other half when the film was finished. It was an absolute dream. I am eternally grateful for that opportunity at the start of my career. Since 1981, I have had to sing for my supper again.

I also get money from The MacArthur Foundation, sometimes the Sundance [Documentary Fund] and a small foundation in Boston called the LEF Foundation. I don’t get private investors because it’s not a good investment.

Filmmaker: You have your own distribution company and self-distribute your films. Can you talk about how that works?

Wiseman: I own the film, and Zipporah Films (which is my company) distributes them. I did that because I got screwed so badly with the first two films I made by Grove Press. They were making a lot of money and I wasn’t getting any. So I sued them and I got the rights back. Their phony accounting was absolutely amazing. As a result of that, I set up my own distribution company. Basically one person [Karen Konicek] has worked for me for 37 years, and before that I had someone else for a number of years, and their job is to flog the films. It’s worked out: if the film does well, you get to keep the money and if it does badly, it’s your own fault. It eliminates the whole business of complaining about the distributor. I only do that for distribution in America. For international, I work with Doc & Film out of Paris.

Filmmaker: You’ve made over 40 films and won an honorary Oscar. Do you ever think of taking a break?

Wiseman: As I get older, I find the need to work even stronger because it keeps my mind off the grim reaper. And I always have ideas. Each film is an adventure — I learn something about a subject. It’s interesting, I like to work. I don’t find it a strain to work.

Filmmaker: What inspires you on a cultural level?

Wiseman: I haven’t had inspiration from other filmmakers. It’s more from the novels I’ve read. In an abstract sense, any art form — whether a movie, a novel, a play, a poem, or a painting — you are dealing with the same issues. You are dealing with characterization, passage of time, abstraction, metaphors. So it’s interesting to see how the problems are solved in other forms, because it’s not a 1:1 relationship. By thinking of the way a novel is written or a play is constructed, it helps me to think about the issues I have with the same kinds of problems.

Filmmaker: What are you working on now?

Wiseman: Last year I worked with a choreographer on a ballet based on Titicut Follies which opened in New York at the end of April. And it’s probably going to come to France at the ballet festival [Festival de Danse] in Cannes in December 2019. I hope that it will then go on tour in Europe — that was a big project. I’m also trying to direct a play in Paris next year. It’s a play by Will Eno called The Realistic Joneses which has not come out in France. I am working with a translator now trying to get a French translation, and I hope I find a theater to put it on in Paris next year.