Back to selection

Back to selection

Kit: 10 Favorite Tech Innovations of 2014 (And Perhaps 2015)

I fall into that category of independent filmmaker who, as the need exists, writes, produces, directs, shoots, records sound, edits, even grades their own footage. (What we used to call color correction.) Then again, often times I’m “just” the DP.

2014 was my busiest year ever, and at some point I found myself taking on each of these basic roles. As a result, the scope of my “kit” is necessarily broad, encompassing both production and post. (Kit is a Britishism for one’s working collection of gear, a name I intend to lend to a series of brief tech reviews in this magazine over the coming year.)

I am hardly alone in this. Digital production grows more syncretic each passing year. Camera and camera settings are now a post concern, much as NLE and workflow choices are a production concern. If you’ve had to weigh the merits of 4K vs. HD in terms of capture and storage, you know what I mean.

My list below is entirely subjective, tied to my specific activities as a small production outfit. My ordering implies no rating system. All ten of these items, whether introduced in 2014 or earlier, impacted and enriched my production practices in 2014 and as a result, the quality of my work.

1. Apple Mac Pro

Last May, Apple loaned me a cylindrical Mac Pro for review. It was tricked out to impress: 3 GHz 8-Core Intel Xeon ED, 32GB memory, dual AMD FirePro D700 GPUs. As is my long-term practice when reviewing gear, I immediately dropped it into the workflow of an active post-production project.

Two months later, the night before I had to return the loaner Mac Pro, I went online and bought a new Mac Pro from the Apple Store, spending money I didn’t have. It had become a must-have.

At first I succumbed to its physical charms. It purred on the table in front of me. Did it resemble a shiny robot’s head? A turbine set on end? Kubrick’s monolith? Analogies that fed my imagination. The perfect surfaces and dusky metallic luster evoked a Koons balloon dog. The cowling on top, under which you can slip your fingers, echoed Steve Jobs’ handle on the original 1984 Mac. (A feature he insisted all carriable computers must have, which is why the classic aluminum Mac Pro tower had handles at both ends.)

Yet like all forward-thinking design, functional qualities had come first. The new Mac Pro is a compact chimney topped by a whisper-quiet impeller. Heat is drawn up and away from a chunky triangular heat-sink that forms the Mac Pro’s core. Attached to the three sides of this heat sink are CPUs, dual GPUs, memory, subsystems, and power supply. (Users have discovered the Mac Pro can be mounted sideways on walls or inside racks without jeopardizing venting, a practice Apple has since sanctioned.)

The I/O panel at the back — or front, since I always turn it towards me —p rovides a cluster of up-to-date ports: four USB 3.0, six Thunderbolt 2, two audio out, two Gigabit Ethernet, and one HDMI 1.4 capable of UHD/4K up to 30fps.

The whole package is 1/6th the size of the Mac Pro tower it replaces. I live and work in a compact Manhattan apartment. Yes!

Now, unless you’ve been living under a rock, you know most of this already. But as my friend, postproduction expert Gary Adcock, recently remarked, at this moment of accelerating technology, the computer you use for post shouldn’t be any older than your camera. (Adcock’s Law, anyone?)

As your late-model 4K camera goes about capturing richer images at higher data rates, your NLE workstation must rise to the occasion too, expanding throughput, offering zippier connections like Thunderbolt and faster if not more capacious storage like SSDs or RAIDs. Progress isn’t free.

Only in test-driving the new Mac Pro did I realize how sluggish my beloved early-2011, 17-in. MacBook Pro — the one with which I first fell in love with FCP X and DaVinci Resolve — had become. An aged Mac is but a paltry thing…

And yes, I’ve been shooting and editing lots of UHD and 4K for nearly two years now. RAW, ProRes HQ, and lately XAVC-I.

So, while power is the chief reason the Mac Pro that I felt compelled to buy in 2014 made this list, major kudos to Apple for the many conveniences of the Mac Pro’s innovative design: the de facto I/O panel within easy reach that acts as a desktop patch bay, the extended connectivity between Macs (Connecting two Macs using Thunderbolt) enabled by Mavericks and Yosemite.

Apple’s Notes, a collateral perk, also became critical to my process in 2014 — whether using my iPhone to jot on-location notes about a camera/lens set-up, or recalling the frame rate of a project from months ago, or reviewing the upcoming day’s production schedule in the back of a taxi. On the Mac Pro, for instance, I routinely create notes while editing, which are then instantly available in Notes on my iPhone, Mac Air, and iMac wherever they are. As many have observed, deeper levels of utility in Apple’s hardware are unleashed by its cloud-based ecosystem. The Mac Pro, at the heavy-lifting end, is no exception.

2. Thunderbolt

While we’re on the topic of desktop velocity, Thunderbolt 1 (10 Gbps) and Thunderbolt 2 (20 Gbps) proved indispensable to my editing of high data-rate formats like 4K in 2014.

Comparing Thunderbolt (10 or 20 Gbps) and USB 3.0 (5 Gbps), I found the choice between the two not terribly consequential when using conventional 7200 rpm drives, as drive speed proved to be a throttle. But when interfacing with significantly faster SSDs and RAID systems, Thunderbolt came roaring into its own.

That’s because Thunderbolt 2 raises consumer connectivity to the realm of high-end SAS (Serial Attached SCSI, 12 Gbps) and Fibre Channel (16 Gbps). Thunderbolt cables remain pricey — their small connectors are jammed with micro-electronics that feel warm to the touch — but once you get used to Thunderbolt speeds, FireWire 800 by comparison seems primitive.

Thunderbolt can daisy-chain up to six devices. No match to FireWire’s 63-device daisy-chain limit, but who has ever linked, no less owned, 63 FireWire devices anyway? I typically use Thunderbolt to link my Mac Pro to RAID storage, a Belkin Express Dock that adds FireWire 800 connectivity, and a unique 21:9 “ultrawide” LG display (described below).

When editing high data-rate formats on FCP X, Thunderbolt connects my Mac Pro to a 500 GB Samsung SSD or speedy G-Tech G-RAID 8TB (RAID 0), or both. To mount the bare 500 GB SSD, I use a dual-bay HighPoint RocketStor 5212 Thunderbolt storage dock, which I call “toaster” because its exposed 2.5” and 3.5” SATA drives look like slices of bread that have popped up. (I use my toaster for archiving and back-up too. I load a pair of 4TB bare SATA drives, one as archival master and one as back-up, into the toaster slots. The venerable app Carbon Copy Cloner guarantees the integrity of the back-up.)

Connectivity, of course, is an arms race. A future USB 3.1 with 10 Gbps has already been announced. A future SAS will offer 24 Gbps, and by 2016 Fibre Channel will claim 32 Gbps and later, 128 Gbps. However by that time Thunderbolt 3 will have doubled its throughput to 40 Gbps while using a 3mm shorter connector. Thunderbolt is the future of connectivity for the rest of us.

At the present moment, it’s a godsend.

3. Seagate Backup Plus Fast 4TB Portable External Hard Drive USB 3.0

This is a fast USB 3.0 RAID (RAID 0). Why is it on my ten-best list?

Two state-of-the-art 2.5” Samsung 2TB 5400 rpm drives whir softly inside. Each, with three spinning platters, is barely 9.5mm high — a size breakthrough. Which explains the overall 7/8” depth of the Seagate Backup Plus. Remaining dimensions are 3” x 4 1/2”. This is 4TB you can fit in your shirt pocket!

Or better yet, stash in carry-on luggage as an after-thought. We all know how accommodating air travel is these days. I just got dinged $100 by Delta for an overweight luggage charge on a bag of gear I checked for an indie feature shoot. Only a few pounds over the limit! That was in addition to their standard $25 check-on luggage fee. Every pound counts these days.

RAID 0 means two internal drives, each 2 TB, striped together to form a single 4TB volume. The composite drive achieves almost twice the performance of a single 5400 rpm drive since both drives are read and written simultaneously. Reviews of the Seagate Backup Plus have noted its remarkable speed, always welcome in the field when downloading “original camera master” (OCM) cards, whether SD, CF, QXD or SSD. Especially at the end of the day, when you’re dog-tired and don’t want to watch snail-paced progress bars.

The well-known downside of RAID 0 is that if one internal drive crashes, you lose the contents of the entire composite drive. In the case of four terabytes, this could be a huge loss. So there is risk involved. A second back-up to another, possibly slower, drive is a critical step before erasing any OCM media from the Seagate Backup Plus.

The Seagate Backup Plus is even fast enough to serve as storage for editing, particularly in the field, which I’ve taken advantage of on several occasions. Because the drive is bus-driven, no external power source is needed. For full performance, however, you must use the drive’s Y-shaped USB 3.0 cable, which taps into a second USB port (can be USB 2.0) for additional power.

The Seagate Backup Plus is Mac and Windows compatible. I formatted it for use with Mac. Suffice it to say, it saved my bacon on a regular basis in 2014, particularly while shooting abroad.

4. LG Electronics 34UM95 34-Inch 21:9 LED Monitor

If you’re not a CES junkie, you likely missed the big introduction two years ago by LG and others of 29” “UltraWide” computer monitors. You might not even know that CES is the massive Consumer Electronics Show held every year in January at the Las Vegas Convention Center — taking place as I write this.

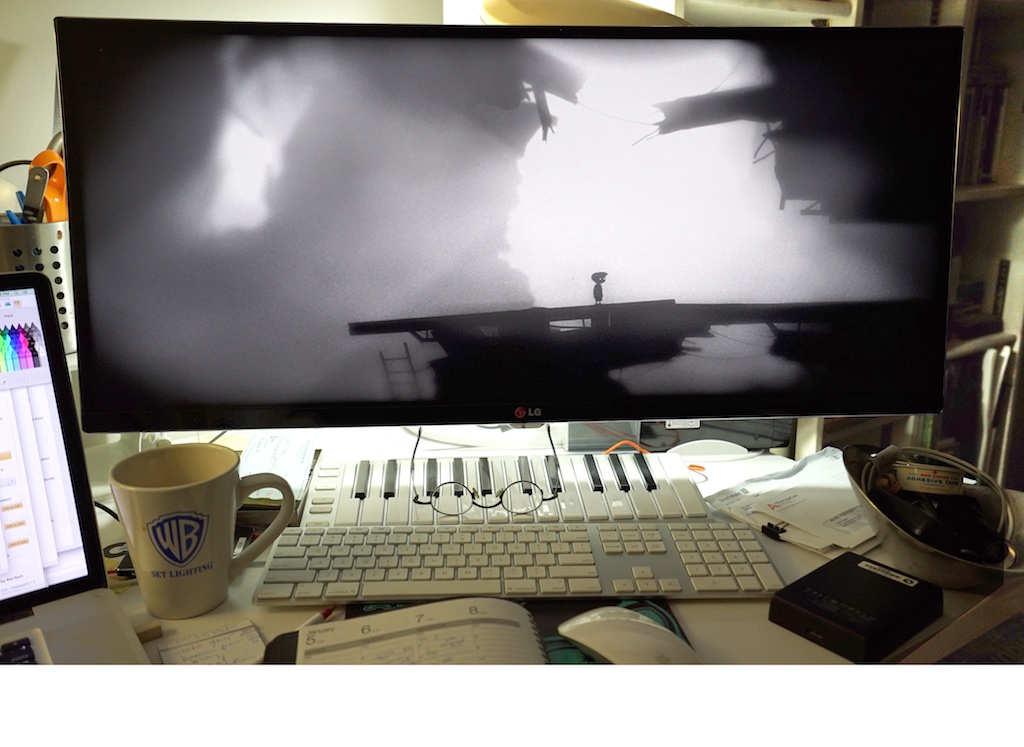

And you certainly would have missed last year’s CES introduction of even larger 34” ultrawide monitors like the LG 34UM95 — pictured above — about which I can emphatically state, for the record, my editing/grading system (and me) can no longer do without.

It boasts 3440 x 1440 pixels. Is it a 4K monitor? Nope. Consumer 4K monitors (Ultra HD) have 3840 x 2160 pixels, and cinema-style 4K monitors have 4096 x 2160. What, then, is it exactly?

“Ultrawide” monitors have a 21:9 aspect ratio, or 2.33, virtually identical to the classic cinema anamorphic aspect ratio of 2.39. The point of ultrawides is their shape, not pixel density. They are to 16:9 monitors what 16:9 displays were to the classic 1.33 shape.

Gamers went nuts for 21:9 for obvious reasons. As workaday computer monitors, however, 21:9 displays bring many unexpected advantages. They function like two standard monitors placed side by side, minus the join or mullion in the middle. You can easily place several script pages or spreadsheets side-by-side, or open multiple apps next to each other. In my case, a single LG 34UM95 replaced two aging Apple Cinema Displays, including duplicate sets of cabling and power supplies.

So I’m here to tell you that 21:9 is the best thing since sliced bread when it comes to displaying NLE timelines. You can see so much more of your timeline at once! Same for DaVinci Resolve. You’ll never again want to settle for a narrow, old-fashioned 16:9 display.

What LG has also done with the 34UM95 is get all the important details right. It is light and thin with a minimal bezel, and held aloft by a clear plexiglass foot that makes it seem to float in air. An LCD technology called IPS gives it a wide usable viewing angle. Backlighting is LED, so color and contrast are superb. Additional specs, features, and helpful user comments can be found at Amazon’s webpage.

But here’s the kicker: it was designed with the cylindrical Mac Pro in mind. Use of the full 3440 x 1440 @ 60 Hz requires the Mac Pro’s dual AMD FirePro GPUs. Connect the 34UM95 to the Mac Pro with a single Thunderbolt cable and you’re off and running, right out of the gate. No fuss, no drivers. You can even daisy-chain an additional two more 21:9 monitors using Thunderbolt. (You’ll need considerably more desktop real-estate.) The 34UM95’s power cable is light and thin too, what you’d expect from LEDs.

So what’s happening this year at CES in the world of 21:9 monitors? Dell, HP, Samsung, have joined the party, unveiling their own new 34” 21:9 displays, some of them curved. However the 34UM95 will be a tough act to follow, as LG has gotten everything right from the start, design included.

Did I mention high cool factor? There’s no better way to explore Playdead’s gloomily expressionistic LIMBO, the perfect editing break (and perhaps cinematic metaphor).

5. Blackmagic Design DaVinci Resolve Lite 11

Announcing Resolve 11 last April at NAB, Blackmagic injected serious timeline editing into its iconic grading system: context-sensitive trimming (auto selection of ripples, rolls, slips, slides, etc.), dynamic JKL control, keyboard shortcuts, use of OpenFX plug-ins, and dual monitor support. That’s in addition to Resolve’s well-known timeline advantages like format independence (RAW debayered on the fly, no transcoding) and perhaps the industry’s best resizing, reframing, and retiming tools.

Consider it Blackmagic’s way of celebrating the 30th anniversary of the da Vinci analog video grading system that first defined professional color-correction. (Blackmagic tweaked the name to DaVinci when acquiring da Vinci in 2009.)

As most know by now, Blackmagic four years ago replaced da Vinci hardware costing six figures with DaVinci Resolve software rewritten for Mac, Windows, and Linux. The new “Lite” version of Resolve cost zero figures — free — a jolt to the industry. The full dongle version cost three figures, $995.

Resolve Lite 11, the current version, limits projects to Ultra HD (3840 x 2160), a single processing GPU, and no noise reduction, but otherwise remains identical to the full version. It streamlines round-tripping to and from FCP X and improves OpenCL image processing to shorten Mac Pro rendering speeds, both of which make me smile. For those of the Avid persuasion, the very latest Resolve Lite 11.2 likewise improves round-tripping with Media Composer 8.3 and supports Avid’s new DNxHR 4K codec, at least for UHD. CinemaDNG RAW image processing has been improved too.

These days I rely on the endlessly capable, astonishingly affordable duo of FCP X and DaVinci Resolve Lite 11. Typically I import 4K in the form of UHD into Resolve LIte 11 — RAW, ProRes, XAVC, what have you — grade and output the result as ProRes HQ or ProRes 4444, then edit in FCP X. I use Resolve’s timeline to trim shot lengths or delete bad shots so that the graded ProRes output contains only what I want to keep, which saves storage and backup. I also crop and resize when necessary.

Without Resolve 11 Lite on my MacBook Pro and new Mac Pro, I couldn’t have finished a handful of key projects in 2014, at least not with the same remarkable image quality. There is no better grading system.

And let me repeat: Resolve 11 Lite remains a free download.

6. Odyssey 7Q + SSDs + Convergent Design cables

Convergent Design’s Odyssey 7Q has been called a Swiss Army Knife: a featherweight 7.7” OLED monitor with iPad-like touchscreen control, a 2K/4K RAW and ProRes HQ recorder that captures to one or two bare SSDs (also featherweight), a multi-scope for fast image analytics. Using an Odyssey 7Q made me feel like I was shooting, monitoring, and recording in the smart-phone era instead of 1995, if you know what I mean.

For example, on a feature I’m shooting with a Sony FS7, I had to pull focus back and forth between two actors swapping remarks while sitting across the table from each other in a dark club. One was near the camera and the other, across the table. I set Odyssey 7Q’s focus peaking to red, then used the zoom feature to enlarge the image to 2:1 pixel size. I used my right finger to slide the enlarged image back and forth between each of the fast-talking heads while my left hand pulled focus at f/2 on a small-barreled Zeiss Loxia 35mm prime lens. It took a little practice, but focus followed dialogue perfectly. Only with an Odyssey 7Q.

As a recorder, Odyssey 7Q can ingest 2K/4K RAW formats from different manufacturers. Since I mostly used Odyssey 7Q for documentary in 2014, I typically captured the 12-bit 4K RAW output of a Sony FS700R to HD using ProRes HQ. Each of two 256 GB SSD held 2 hours and 12 minutes (at 29.97 fps). That’s almost 4.5 hours of uninterrupted shooting! Think of it as 4K RAW captured with S-Log2, instantly deBayered and downsampled to HD, then recorded with edit-friendly 4:2:2 ProRes HQ. In other words, the look of 4K at the low cost and convenience of HD.

The SSDs, which must be branded Convergent Design and sport CD’s pull tabs, use standard Mini-SATA connections, meaning any bus-powered USB 3.0 or Thunderbolt docking cable will connect Odyssey 7Q’s SSDs to a laptop for downloading in the field. I typically download to fast, portable drives like the Seagate Backup Plus Fast 4TB described above.

Whether handheld or tripod, what works best for me is to attach Odyssey 7Q to the rear of the camera using 15mm rods and an adjustable Noga arm from Vocas. I use the same small Sony L-series batteries as the camera, which saves weight — I hate bricks — and eliminates a second charging system.

Everything about Odyssey 7Q is fast, lightweight, convenient, and thoroughly 21st century. Call me a happy clam, but the only future improvement I can think of is wireless connection to the camera when the technology permits. Meanwhile, Convergent Design has given us the next best thing, the thinnest 3G-SDI cable possible. Light, flexible, easily managed on the camera — nothing like the heavy, stiff BNC cables we’re accustomed to. (Thank you, Mitch Gross, for insisting I try them.) Sending 4K RAW from a Sony FS700 to an Odyssey 7Q to record HD requires just one of these cables. Even if you have yet to encounter the advantages of Odyssey 7Q, you’ll want to own these innovative spaghetti-like 3G-SDI cables for your camera’s digital output. They’ll feel like 2015 to you.

Everything about Odyssey 7Q is fast, lightweight, convenient, and thoroughly 21st century. Call me a happy clam, but the only future improvement I can think of is wireless connection to the camera when the technology permits. Meanwhile, Convergent Design has given us the next best thing, the thinnest 3G-SDI cable possible. Light, flexible, easily managed on the camera — nothing like the heavy, stiff BNC cables we’re accustomed to. (Thank you, Mitch Gross, for insisting I try them.) Sending 4K RAW from a Sony FS700 to an Odyssey 7Q to record HD requires just one of these cables. Even if you have yet to encounter the advantages of Odyssey 7Q, you’ll want to own these innovative spaghetti-like 3G-SDI cables for your camera’s digital output. They’ll feel like 2015 to you.

7. Sony FS700 and FS7

Sony’s FS700R arrived late 2013, while the expressly ergonomic FS7 debuted late 2014. Both E-mount cameras opened new horizons of 4K capture and output in a S35 camera under $10K.

In addition to coupling the FS700R to an Odyssey 7Q as described above, I have captured 4K repeatedly with a Sony AXS-R5 RAW Recorder via an HXR-IFR5 Interface Unit. With a brick battery attached, this R5+IFR5 combo becomes, well, a much bigger brick, albeit with a handle. Which I admit I therefore set on the ground or hang from the tripod, tethered to the FS700 by a single wisp of a long Convergent Design 3G-SDI cable. But the upside of this awkward arrangement is that I can record 4K RAW up to 60 fps and 120 fps in four-second bursts (20 sec’s of slo-mo at 24 fps) to a Sony 512GB AXS card in a simple, straightforward manner. In my experience, bullet-proof.

The mildly compressed RAW files (under 3:1) contained in Sony’s .mxf wrapper are easily opened and instantly debayered in DaVinci Resolve, Sony’s RAW Viewer or Sony’s Catalyst Browse (both free downloads, Mac/Windows). Fast previewing and nondestructive grading of clips is possible in all three apps. I often go a step further and output the results as ProRes HQ or ProRes 4444.

Through S-Log2 gamma, the FS700 opens up a world of expanded tonal range capture beyond REC 709, while the FS7 through the combination of S-Log3 gamma and extended color gamut S-Gamut3.Cine (larger than P3) takes us to the latest frontier of color space.

There are many ways these days to skin a digital cat when shooting sophisticated images, but for those on a budget, these cameras deliver like no others.

8. Canon Dual-Pixel autofocus

If you shoot a lot of handheld or documentary with S35 cameras, you dream of a perfect autofocus system. And now with 4K, the focus stakes are higher. When a person shifts their body or head in close-up, their eyes can slip from perfect focus. You won’t see it in the viewfinder — and I guarantee you will feel sick about it later, watching the slightly soft results on a bigger screen. Now imagine trying to keep a fast-moving subject in focus!

Image magnification helps. So does peaking in the viewfinder, but a reliable, near-instantaneous autofocus system that locks on, and accurately tracks, focus without hunting and pecking would be another godsend. Well, it exists.

Canon has taken the best of contrast-based autofocus (it achieves rough focus rapidly) and phase-detection autofocus — it deduces instantly whether precise focus is in front of or behind the subject, no guessing — to create a hybrid autofocus system that, incredibly, is integrated into the surface of their latest CMOS sensors. No lens adapters needed.

Canon’s Dual Pixel Autofocus is, hands down, the best autofocus I’ve ever used, and I’m hooked. Rather than describe its attributes in words, I made a short demo video. Just scroll down to the bottom of the webpage, past the other videos, to watch it.

Available initially as an upgrade to the C100 and EF-mount version of the C300, it’s now standard in the recent C100 Mark II and latest EF-mount C300.

Incidentally, “Focus Pixels” in Apple’s new iPhone 6 is the same idea. Since Sony makes the iPhone’s iSight sensor, it’s perhaps only a matter of time before this magical technology spreads to other cameras. In the meantime, Canon is the only game in town. As with optical image stabilization, also a Canon breakthrough, they have produced another essential new technology.

9. Zeiss E-mount Touit lenses

Compact mirrorless cameras are already making chunkier DSLRs with mirror shutters look oh-so-last-century.

With mirrorless cameras come new lens mount systems with remarkably shallow flange focal distances. Panasonic’s Micro Four Thirds is only 20mm, Canon’s EF-M and Sony’s E-mount, 18mm.

This sets the stage for lenses designed for mirrorless cameras, optically superb but less expensive, and increasingly available for use on digital video cameras.

Sony’s popular E-mount, for instance, has evolved to support both APS-C (equivalent to S35) and full frame. Both sensor sizes are found on both video and still camera models. Taking notice, Zeiss has introduced a new “Touit” series of low-cost, lightweight E-mount primes for APS-C only. While not appropriate for a full-frame camera, they’re perfect for a light S35 camera like the Sony FS700 or FS7. The Touit series so far includes 12mm f/2.8, 32mm f/1.8, and 50mm f/2.8, all under $1000.

Each is minimal in design, virtually no markings. A single big rubber ring controls focus. These lenses are electronically controlled: iris is dialed up or down from the camera.

I’ve shot shockingly sharp 4K with the 32mm, which remains crisp at f/1.8. The 12mm Touit I use the most. It’s a terrific wide-angle lens to have handy in your kit. Minimal geometric distortion.

If you prefer entirely mechanical lenses, Zeiss has also introduced a new “Loxia” series of E-mount lenses, including a 35mm f/2 and 50mm f/2. These are about the same size and price range as the Touits but all-metal and heavier. They are also full-frame. The manual aperture ring can be de-clicked. The 35mm I used recently on an FS7 to shoot a feature, during which I had to pull focus as described in the Odyssey 7Q section above. Yes, the barrel diameter is small, but indie feature filmmaking is a motherlode of invention.

Incidentally, Touit and Loxia are the names of birds, namely parrots and finches.

10. Larry Light

Years ago, early ‘90s I think, there was the Larry Bag, a boxy, stiff-fabric bag designed by New York camera assistant Larry Huston for other camera assistants. That my favorite new flashlight turns out to have the same name is wacky coincidence. The original Larry Light a decade ago was knurled aluminum with a lithium camera battery inside, created by a Nevada inventor named Larry. The latest Larry Light, easily mistaken for a plastic pen, was co-designed by an American and Chinese partner according to its 2014 patent, neither remotely named Larry. Still, the friendly name endures.

Bucking flashlight convention, the Larry Light has no reflector or lamp at one end. Instead a line of eight bright LEDs are arrayed along the side opposite its magnetized pocket clip. This clip — great for sticking a Larry Light to metal surfaces — rotates around the flashlight’s body to act as an adjustable flat surface to position the flashlight on its side without rolling away.

Big whoop, you say. A flashlight is a flashlight. But locate me on a dark set in 2014 and you’d see a Larry clenched in my teeth as I adjusted camera settings or leveled a tripod. For some reason camera manufacturers offer any color of camera as long as it’s black (an old Henry Ford joke). They also insist on tiny black buttons and controls marked with miniscule lettering which are impossible to see in dark environments. Muscle motor memory of where certain buttons or switches are located — always risky to push any button you can’t see while shooting! — doesn’t work for me because I use an assortment of cameras from different manufacturers, depending on the project.

I bought my first $11 Larry Light on a whim at a hardware store in Great Barrington, MA. Manufactured by Nebo Tools, the Larry Light is widely available on the Internet, i.e. Amazon. Inside the Larry Light are three standard AAA batteries, available anywhere, which power the Larry Light for three hours. The Larry Light is turned on by a single button push at the end above the pocket clip. No gimmicks, no multiple levels of brightness, no emergency flashing — just basic on and off.

I’ve got Larry Lights in various colors socked away in my kit bag, car glove compartment, backpack, and while shooting, pants pocket. (Doesn’t dig holes.) I give them as gifts to friends. My most versatile new gadget of 2014.

What might make my list in 2015:

1. Camera drone

I almost bought a DJI Phantom Quadcopter on the spot at NAB last year for a project about the construction of the new Cornell Tech campus on Roosevelt Island in Manhattan’s East River. An old, historic teaching hospital was first being torn down, and aerial demolition footage would have been riveting. Price was right but concerns about image quality nagged. Glad I held off. These affordable flying eyes in the sky will only get more impressive this year. NAB 2015 just announced a new exhibit area, the Aerial Robotics and Drone Pavilion.

2. Sony a7S

I borrowed a Sony a7S to shoot vertically framed HD of Niagara Falls for an art project last September. Despite an APS-C center crop and 8-bit, 50mbps recording to an internal SD card, the footage was utterly spectacular. While the a7S resembles a compact DSLR, it’s the apex of a new generation of mirrorless, full-frame, interchangeable-lens cameras which are as adept at capturing video as stills. The a7S is further distinguished by 1) a native Ultra HD 3840 x 2160 sensor and internal UHD processing, 2) enlarged photosites for unprecedented ISOs up to 409,600, 3) uncompressed UHD output via micro-HDMI, and 4) an E-mount just like the FS700 and FS7 I already shoot with. S-Log2 gamma and XAVC-S compression further help the a7S to better match those two cameras.

ProRes recorders I might connect to an a7S in 2015 include, for HD only, the Atomos Ninja Star, and for UHD and HD, the Atomos Shogun 4K Recorder and, of course, Odyssey 7Q.

As was the case with most of my 2014 10-Best list above, having tried the a7S, I ended up buying one. On Dec. 31, that is, for tax reasons. Which is why I look forward to exploring the a7S in 2015.

3. LT0-7 storage with Thunderbolt

I’ve long advocated optical storage for archival purposes — I’ve followed the development of Sony’s Optical Disc Archive system and field-tested it — but the exponentially expanding storage demands of UHD and 4K, not to mention their archival needs, have undercut the appeal of optical media, at least for the time being. The only alternative to shelves upon shelves of hard drives and cloned backups, therefore, is LTO tape.

LTO tape cartridges compared to hard drives are inexpensive and bring significant advantages: no drive motors, no platter spindles, no read heads guaranteed to fail someday. And LTO tapes are now friendlier too. The recently standardized LTFS (Linear Tape File System) permits LTO tapes to be mounted, searched, and copied just like any external hard drive.

Nonlinearity aside, the issue for me regarding LTO tapes remains capacity. Current-generation LTO-6 boasts 6.25 TB per cartridge, but that’s based on 2.5:1 compression not appropriate to digital video files, already highly compressed. The native capacity of LTO-6 — its true capacity for storing video files — is only 2.5 TB per tape, and that doesn’t cut it for me.

LTO-7, which, fingers crossed, arrives later this year, hikes tape native capacity to 6.4 TB. Now we’re talking. Only issues remaining would be LTO-7 drive cost and consumer connectivity. Present LTO-6 drives use a type of SCSI called SAS. But we need instead — so obvious! — Thunderbolt or USB 3.0. At NAB 2014 mLogic introduced an external LTO-6 drive with Thunderbolt for $3600 (street price). Let’s hope 2015 brings many more such Thunderbolt LTO drives. Competitive prices would be nice too.