Back to selection

Back to selection

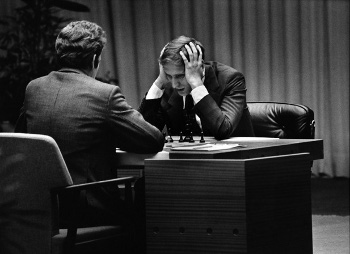

“BOBBY FISCHER AGAINST THE WORLD” DIRECTOR LIZ GARBUS

For the lucky few who get in, Sundance isn’t just a festival — it’s a resource. Over the years, the festival has nurtured the careers of a number of documentary filmmakers who went on to become what senior programmer David Courier recently termed “master filmmakers” — filmmakers so good and so respected that the festival had to create the out-of-competition category, “Doc Premieres,” to make sure their work didn’t overshadow the greener directors.

It should come as no surprise to anyone in the documentary community to find Liz Garbus’ name in a category reserved for such filmmakers. Garbus’ history with the festival stretches back to 1998 when her feature, The Farm: Angola USA won the Grand Jury Prize. In the 13 years since that debut, Garbus has gone on to direct a number of films that would premiere at the festival, including The Execution of Wanda Jean.

Not content to simply be one of the most prolific documentary directors of the decade, Garbus is also one of its most influential producers. Together with Rory Kennedy, she co-founded Moxie Firecracker Films, a company that has nourished a number of directors including Marshall Curry and Liz Mermin. I recently spoke with Garbus about Bobby Fischer Against the World, her film about the famously reclusive chess champion, which will premiere at the festival.

Filmmaker: Both you and your producing partner, Rory Kennedy, are known for directing documentaries that illuminate a social issue slant about ordinary people. What attracted you to the story of Bobby Fischer?

Garbus: I think that’s both true and not true in terms of my films. I’ve made a few films that were out of that genre, including one I did that aired on A&E, The Nazi Officer’s Wife. What attracted me to Bobby Fischer was the storytelling challenge and the amazingness of the story. As a filmmaker, it was a gratifying story to tell, a great rise and fall, but his life didn’t exist in a bubble. He was a sort of pawn of Cold War politics, so we certainly set his story in that context.

Filmmaker: With historical docs, it’s always a struggle to figure out how much context the audience needs to understand the story.

Garbus: It is a challenge. There’s something we refer to as “the Cold War exposition section.” It was always a moving piece that finally had to settle in somewhere. This is a film about a person, about a sports match. It was a time when all of our nation’s hope centered on one person. He was a warrior against the Russians when that was issue number one. It was a challenge how far into the Cold War we needed to go. We use it as a backdrop, a sort of wallpaper, but it’s not the crux of the story.

Filmmaker: Later in his life, Fischer became something of an infamous crackpot. How did you approach making a film about someone who became known for saying awful things?

Garbus: There are two things, two stories, the story of this child prodigy that grew up to represent America in the world and who participated in this sports match that riveted the whole world. Then there was this man who became a recluse, an anti-Semite who becomes despised as anti-American. How do you create empathy with a guy who said that 9-11 was a good thing? The answer is that you try to understand their psychology, their mental illness.

Filmmaker: Much of your work has been verite, where you are filming stories as they happen in the present. Was it difficult to make a story that took place completely in the past?

Garbus: Very few people wanted to talk about him. It was all about building trust and peeling away layers to get people to talk about Bobby who had never done it before. After 1972, Bobby became a recluse who didn’t want to be photographed. It wasn’t just that you had to make his story more present, it was that even in the present, he wasn’t there. We had to turn over every stone to make that part real. We found an archive with over 2,000 photographs. We found footage where he spent his last years in Iceland and got footage from someone that was shooting his last years.

Filmmakers: Did you find yourself feeling attached to Fischer, even though you never had an actual relationship with him? How did you navigate that?

Garbus: It’s a good question. Whenever I would find a new picture or a diary writing or a letter, it was like getting this gift from the grave because I never thought I’d see Bobby at such and such a time… You’re sort of in love with this person and looking for every scrap of them that’s on this planet, and then again, this person, well his behavior becomes painful and unacceptable. I mean, I’m Jewish, and he said terrible, anti-Semitic things. At the end of the day, I viewed him as someone suffering from a mental illness, so I empathized with him.

Filmmaker: One of the things that interests me about Fischer’s story is whether there’s some connection between his mental illness and what made him so good at chess.

Garbus: I don’t believe that playing chess makes you crazy, but it does [involve] a certain kind of monomania. Imagine that starting at six years old, everything you do is chess. Your whole social personality, your whole intellectual personality is seen through the chess board. Chess is war over the board, and that’s an intense way to grow up. There are plenty of very, very sane people who are good at chess, but I do think that monomania from such a young age on chess or any sort of art form can make you feel isolated. That certainly happened to Bobby.