Back to selection

Back to selection

Christopher Doyle, Live and Uncut, at the Big Screen Symposium

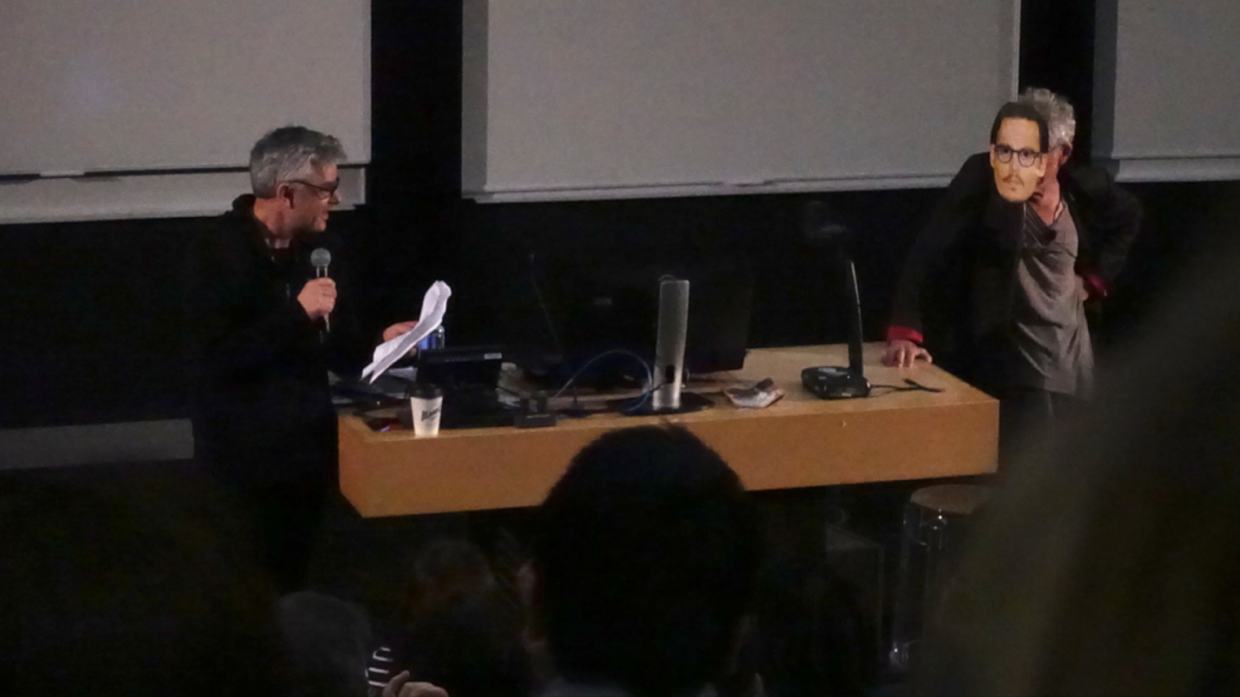

Vincent Ward (left) and Christopher Doyle in Johnny Depp mask

Vincent Ward (left) and Christopher Doyle in Johnny Depp mask Screen luminaries from around the world are invited once a year to New Zealand for its annual industry gathering, the Big Screen Symposium. Last year, guest speaker Sebastiàn Silva (Nasty Baby, The Maid) shared his horror stories of working with Christopher Doyle, who (Silva claimed) exposed himself to everyone on the set of Magic Magic, refused to shoot close ups (“That’s HBO bullshit”) and generally caused chaos. When Doyle himself was announced as a guest speaker for this year’s event, it was clear the Symposium intended to take the announced theme of “Playing With Risk” quite literally. And so from the opening introduction by director Vincent Ward, which Doyle disrupted with clowning, shouting (“I can’t even be tolerated, let alone moderated!”), adding Mark Cousins to the list of filmmakers he’d worked with (“If you don’t know Mark Cousins, you don’t know shit!”), then crashing the stage while wearing a Johnny Depp mask, it was equally clear that everyone would get, perhaps, exactly what they’d bargained for.

Over the course of back-to-back sessions — one slated as a breakout talk on cinematography, the other optimistically billed as an “electrifying” general address on his “insights, philosophy, and passion for creative daring” — Doyle spat out sentence fragments and chased trains of thought. He teetered between court jester, Zen master, politically incorrect agitator, self-aggrandizer (the Depp mask being a reference to him as the Keith Richards of cinematography — whether Doyle was unaware of Depp’s recent negative press or intentionally provoking the audience was highly unclear), self-deprecator, and humble explorer. Was he a general shambles, or a stunningly practical genius capable of using his skills not just for aesthetic rapture but also cost-efficient results that would make a producer’s heart sing? He was both. For attendees expecting an organized, inspirational and focused lecture, it was an exercise in maddening frustration; for others, including myself, it was like panning for gold, muddy boots and all.

Herewith, a few nuggets, presented with the caveat that Doyle himself gave at the outset: “Not everything I say is true. That’s why it’s valid.” (And no, he didn’t expose himself. At least, not during the sessions.)

Break down barriers between the actor and audience.

One central thesis of Doyle’s is that there are three people in filmmaking. Exactly who those three are varied from moment to moment — “you, me, and the camera in between” and “script, shooting, editing” were two triads — but the common notion was about getting rid of barriers. “Eliminate egos, get the technical stuff out of the way, and let the actor communicate with the audience.” Doyle beseeched directors to “fucking get out of your video village” and go where the connection is happening – between the actor and the camera. “If you sit back and you’re not engaged, how can the film be engaging?” A distilled example of this was provided in his captivating film of Tilda Swinton, a collaboration between the two of them, partially shot using a Lensbaby (which he compared to shooting through a beer bottle).

As an aside, Doyle’s lack of fussiness about having “the best” technology, and instead his focus on exploiting the particular plastic qualities of the technology he uses to capture the most out of a moment, is one of his most striking qualities as a DP. One clip he showed of him capturing the play of light on the beach off a low-grade consumer digital camera, which he claimed was the moment he decided to become a cinematographer at the age of 32, was a stunningly effective provocation for all of us to consider what was at the heart of our personal creative journeys. He was similarly unfussy about the clips that he showed from his films. “Most of them are ripped off pirated Chinese DVDs … Don’t tell customs.”

Get past the script.

Breaking down barriers extends to getting rid of the script. “I understand what the intent of the script is, then I throw it away … how can we get somewhere special that wasn’t in the script?” This concept doesn’t always play well with writer-directors, but Doyle’s argument, roughly, is that they aren’t in the room three years ago where they wrote that script — they’re filming now, and they need to understand the best way to capture the intent of the scene now. “The pleasure is engagement. That’s what it’s all about … if it’s not about engagement, it doesn’t matter.” Perhaps this is why he’s drawn to keep directing Asian films, which he considers less bound to the 3 act structure (which he claimed to not remember the name of, but compared to the three crosses at the crucifixion) and more like a sand mandala that one moves closer and farther from.

Use feng shui to control difficult actors.

I’ll redact the name of an actor Doyle mentioned, as in a rare display of propriety he second-guessed himself after mentioning it publicly. So, well, “JI” — and also the actor only identified as “RF” — both indulge in what Doyle describes as six-hour discussions about a character’s motivation for opening a door. The solution? Feng shui. “Light the set to get them where (you want the actor) to go … just trick them into thinking it’s where they belong.” If you want the character to go through the window instead of the door? Light the window. The extent to which this played on human psychology vs the vanity of the actor was left unexplored, but one could make assumptions.

Adapt your craft.

It’s tempting to think of Doyle as having an iconic look, given his films with Wong Kar-Wai, but a brief scan of the rest of his CV — Rabbit-Proof Fence, Ondine, Liberty Heights, Underwater Love, Hero — puts paid to that notion. While in some cases that’s directorial control — apparently, on Lady in the Water, M. Night Shyamalan made Doyle frame to match Shyamalan’s storyboards so precisely that the director would make him move his frame if the window behind a character was in the wrong place — Doyle would occasionally let slip his creative problem-solving to difficult situations, albeit under cover of self-deprecation. Working with three non-professional young girls on Rabbit-Proof Fence who would do different things in every take, he relied on using a zoom lens and reframing three times within a take to get coverage that would work for every take, a tactic he described as “laziness.” It’s one of Doyle’s central enigmas that despite his tendencies as a personality to create chaos, his creativity is borne out of responsiveness: “I’m better responding to other people’s energy than creating the energy myself.”

Forget what you know.

Is there a method to Doyle’s madness — by which I mean his presentation? While he willingly plays the part of the buffoon and constantly undercuts/remythologizes himself (his pride in finishing the challenging day-for-night shoot of Ondine five days early was promptly undercut by his claim that he had to leave town because he owned the tavern money), it seems borne of a suspicion that confidence in one’s knowledge is the enemy of the engagement he values. He loves working with first-time directors because “they ask the stupidest question … the stupidest questions are the most important. You have to forget what you know.” In answering questions about Hero, he mentioned how stunned he was that Zhang Yimou seemed not to care about lighting continuity, shooting scenes that shifted from bright sunlight to pouring rain; similarly, Doyle felt the blue sets in particular were absurd and fake-looking. It was only in seeing the final film that he understood what Zhang was up to: “It looked fake, but it worked.” Those in the audience looking for principles and rules they could take away from his lecture were undoubtedly disappointed, with Doyle providing only one certainty: “Graduating from film school doesn’t help. It’s only good for your sex life.”

Be humble. Or don’t.

Doyle repeatedly emphasized the importance of humility, which sometimes came across as deeply heartfelt and other times seemed risible coming from the self-described Keith Richards of cinematography. When a brave questioner asked a follow-up question, he cut him off: “You actually believe that bullshit?” But it’s clear that, underneath the bluster, Doyle knows what his legacy is. He spoke of his lengthy collaboration with Wong Kar-Wai (seven features, three shorts) as in fact making one big film, a process he compared to making sculpture: “take a big piece of rock, get rid of extraneous stuff … we’re just getting rid of the shit (each time we work together) … until we made a film called In The Mood For Love.” A clip from a BBC doc where Doyle discussed the creative evolution of a key scene from that film distilled into two cogent minutes Doyle’s genius for finding the mood and heart of the scene outside of the script. He grew philosophical when a questioner (barely audible from my vantage) seemed to ask, more or less, what the hell had happened to Wong Kar-Wai after that. “We got there, and what’s happened since? How do you move on? Maybe you don’t.” In retrospect, it made his opening clip from the first session — footage from Happy Together scored to a honky-tonk version of U2’s “I Still Haven’t Found What I’m Looking For”—- seem less like a gag and more like a mission statement. “You know what my best film is? My next one.”

My last note from Doyle’s first session is this: “You cannot control the world.” This is true. You cannot even control the small part of the world that is Christopher Doyle. He ended his second session — one where he’d rubbed attendees the wrong way repeatedly, most notably by describing continuity people as “generally unhappy women” — by yelling “I forgot the most important clip! Play the porn clip!” While said video largely consisted of audio interviews with porn stars at an awards ceremony, with only the briefest visual allusion to oral sex, it left many feeling as discomfited as if Doyle had ended by taken his pants down. Presumably, he wouldn’t have had it any other way.