Back to selection

Back to selection

6,500 Kilometers in 29 Shooting Days: Jérôme Reybaud on 4 Days in France

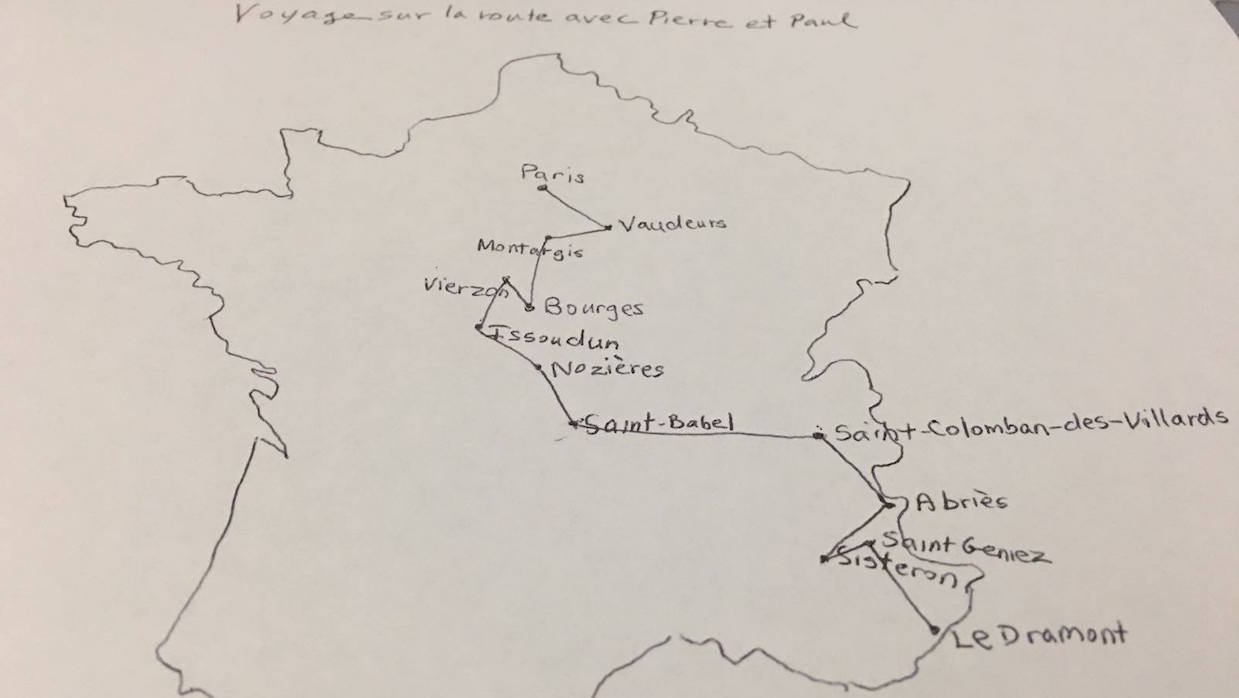

The start to finish route of 4 Days in France (Drawing by Sylvia Savadjian)

The start to finish route of 4 Days in France (Drawing by Sylvia Savadjian) I wrote a little bit about 4 Days in France yesterday; a few hours after publishing, I went to meet writer/director Jérôme Reybaud to follow up on some particular points of interest. Some basic plot points about this recommended quasi-romance/road trip narrative: a great deal of the film follows two men driving cross-country across France (one in pursuit of his just-left partner until their routes converge) to an extensive collection of classical recordings, stopping at locations including the top of the very cold Alps, a used bookstore, a theater, and an encounter with a notably aggrieved lady who chews out one character when he stops at a cruising stop near her isolated house. (NB: this interview gives away the ending, though it’s really not that kind of movie.)

Filmmaker: The main question, which you talk about in the press kit, is the logistics. I know they’re driving on the real roads and that that was important to you. How did you organize that? They’re going from one place to another, which takes time, and you had to take into account the time of day, traffic and the fact that there are two of them.

Reybaud: At the beginning, it was very hard for the crew and production to understand the necessity of having the real roads, but it was the main point of the movie, so we had to do that. The roads were all chosen during the writing two or three years ago. Before shooting, we went to see all those roads, and two or three were impossible to film, just because of the trucks and danger. So I had to make some changes — very few, but some changes, which were [incorporated into] the script. For example, the young homosexual at the beginning was in a little town called Châteauroux, and it’s very difficult to shoot there, so the production asked me to find another place. We found the city of Bourges, and in the dialogue you can hear the word “Bourges.” So I don’t act like he was in Châteauroux.

Filmmaker: Why was it difficult to shoot in Châteauroux?

Reybaud: I remember — the money! We had, on the whole, 29 shooting days, including the trip, over 6,500 kilometers of France. So shooting in Châteauroux [just] for this character lost a day or half a day, so I had to make a compromise, but there were very few. The unit production manager, Aurelie Delvenne, was the woman who made all these roads possible. At the end of the shoot, I was just throwing numbers at her: “62.” And she remembered that 62 was the name of this road from etc. So she really had the geography in mind just like I did.

Filmmaker: So did you take a map and just draw it out?

Reybaud: This girl, Aurelie and her crew, drew lines on these maps, so Auvergne, Provence, Cote d’Azur, Paris etc. — they just did what was written in the script. Amongst those 100 little roads, they said “This one may be a money problem,” because it’s very far away or security problems, or refusal from the authorities, because we had to ask for almost every one. But sometimes we didn’t ask. For example, in France to shoot on the motorway, I think we must spend 6,000 Euros. So, we said, “We’ll just do it like that [without permission].” But every road was in the script, and we checked them one by one.

Filmmaker: Had you driven a lot of them yourself?

Reybaud: Yes. Sometimes I was writing and couldn’t go further, so I took my car and would just to go there to find the road I wanted to find. Sometimes it was a road I knew from two or three years ago, and I wanted to see it again to see if it was the road I wanted to show in the movie. Sometimes I had an abstract of the kind of roads I wanted, so I had to find a particular road matching this idea I had beforehand. So, I used my car and Google Maps a lot.

Filmmaker: What were the kind of different roads you were looking for?

Reybaud: I wanted all kinds of roads. It’s the same as the ages of the characters: you have boys, old women, the whole spectrum of ages, and it’s the same for the landscapes. The main landscapes of France are in the movie, and it’s the same for the roads: motorways, obviously, but also feeder roads. These roads don’t have the poetry or beauty that motorways can have sometimes. At the other end of the spectrum, there are little roads without any name. So they are all in the movie. At the end of the movie, the woman who lives in the Alps alone says that the asphalt on the road just stops, and then the road continues and it’s just rocks. Then it just ends, because it’s a mountain. So that’s the smallest kind of road.

Filmmaker: It seems like shooting at the top of the Alps would be particularly difficult. It’s obviously very cold and windy for real.

Reybaud: At the beginning, it sounded like a problem, but in fact it was wonderful news. I was shooting some things with that woman, and we had a phone call because Aurelie was at the top of the mountain, preparing for the shoot, and she said “I can’t go there because of a snow tempest.” I don’t know how she did it, but she found shovels, she was incredible. So the whole crew couldn’t up top, but we could with the actors. I was very happy: at the beginning, I meant to shoot on a beautiful, sunny day because you could see this sign [marking the border between France and Italy] and behind it you could see this incredible view of Italy. Stupidly or mythically, we invest the two landscapes with different sentiments: this is France, this is Italy. It’s exactly the same, but for me it’s not the same, just because I’m told there’s a line there. So I wanted to show that, but I had a wall of fog and that was much more interesting. So it was quite hard, but it worked. I had a real chance to shoot on the road, and the main chance, the main uncertainty, came from the weather. Because we didn’t have the time or the money to stay in place, so if we didn’t have the shot, we didn’t have the shot and we had to go, because we had to go 100 kilometers or wherever. So the weather was the danger. Sometimes people ask me if there is improvisation in the movie. In fact, there is absolutely none. Everything was written, except one part, but the weather was not written, so I had to deal with it. So that’s the main example of the weather intervening.

Filmmaker: Which part wasn’t written?

Reybaud: The lady that is very angry about Pascal cruising in the woods. At the beginning, I didn’t want an actor. I wanted a real neighbor from this place, because I do a lot of cruising, and when I do that, I think about those people. And I think, “If I was living in this house, I would be hysterical. I couldn’t stand the noise.” Because those people are living in the woods. They want nature and silence, and we are with our cars in the night and it’s terrible for them. So I said, “I can’t just show a pretty Parisian gay guy doing whatever he wants in the woods of France, just like that, and nobody cares, everything is fine.” No, it’s not fine, because sometimes it’s dirty. So I wanted to give the camera and mic to a real person, saying, “I can’t stand it.” Not homophobic, just, “I can’t stand the noise, etc.” and of course, nobody wanted to say that on camera. So I had to take an actress I love, and I said, “I don’t want to write this, just improvise.” And she did. She had made a lot of movies with Paul Vecchialli, and she made a French movie in New York in the ’80s that I haven’t seen, a kind of Cruising. She said to me after, “You broke my only public,” the gay public, but I think she’s wonderful in that scene.

Filmmaker: So how much ground did you cover on average, or was it staggered?

Reybaud: Sometimes we had to make big steps, and sometimes we stayed for four days in one place. For example, the last scene was shot on the sea at Cannes. We had 15 minutes of the right light, so we had to install the set at night by four in the morning. At five we were ready, and at 5:30 we could take one, two, three shots. After that, it didn’t work. So I remember that after we made a five or six hour trip to go back to Auvergne. It was quite difficult to make the shooting schedule, because the actors were coming from every place: one was coming from Berlin. The guy who plays Paul was doing a Moliere play, so sometimes it was almost impossible to find a train from the little town he was acting in to where we were.

Filmmaker: Did you shoot first one character and then the other?

Reybaud: No. At first we wanted to go from [the starting point of] Paris to [the end point of] Cannes, but it was not a good solution practically. I don’t care, so I said to the actors, “Do you care?” They didn’t mind, so OK. In fact, the first shot of the whole movie was the last shot when they meet together and kiss. So there were sequences with both of the actors, even if they’re not in the same sequence, but if they were near we shot them.

Filmmaker: Were they both good drivers?

Reybaud: Arthur Igual is a good driver, and he loves to drive, and he drives fast, which was perfect for me, for the character — he’s after something. But for Pascal, one of the most difficult things to do in the movie was to appear quite normal while driving this car. We made a lot of trips together before the movie, two or three months before shooting, because he was driving my car, so we went driving so he could get used to it. It’s quite a little car, and the camera was on the hood sometimes, so it was difficult for him. The long sequence at the beginning of the movie with Fabienne Babe, who sings in the retirement homes, was a long sequence without cuts. There is a cut in the final movie, but it was shot without cuts — I don’t know, seven minutes. So he had to deal with his dialogue, her dialogue, driving and the camera on the hood, and with us outside. So it was very difficult, but I wanted this difficulty, because I knew it would give them both this kind of fragility and weirdness you can feel when you are hitchhiking and you have someone you absolutely don’t know close to you. I did a lot of hitchhiking in Cannes, Nice and the Cote d’Azur when I was 17, and it’s very strange to be with a complete stranger — you can feel and smell them, and sometimes the discussion is very intimate, if rarely. So the difficulty of shooting this sequence was, I think, a good thing for the characters and the way they played it. There was only little accident, a scratch on the front.

Filmmaker: For a lot of people, shooting a movie with so many driving sequences would be the ultimate nightmare.

Reybaud: Yeah. My cinematographer, Sabine Lancelin, hates shooting in cars. During the shooting, she was like “Cars? Still cars today?” She was not happy, but deep inside I think she was happy because it’s very difficult. Technician guys and the crew love difficulties, in fact. It’s like something you give them to think about.

Filmmaker: Did you select specific recordings of the classical pieces, or did you just choose for what’s most affordable for each piece?

Reybaud: It’s just like the places. I chose the music during the writing, so I had to find the music to be able to complete each sequence. It’s my first feature film; before, I had just made a few short movies and a documentary, all of which I made almost completely by myself — the camera, sound. I read about the cost of music in cinema, and in my way of searching for the classical pieces, the fact that those pieces are costless is a given for me. My producer was telling me, “It costs a lot!” I said “No, don’t worry,” and one day I gave her the list and almost all of the recordings were recorded before ’56 or so, so no copyright costs in Europe. She said, “Wow!” There are some exceptions: we had a little money for music, so I could afford one or two specific recordings — for the Rameau piece at the end when they meet, I was happy to be able to get the modern recording. I listen to a lot of classical music, and a lot of classical music from before the ’50s or ’60s, so they are free. One of the great directors I admire is Eric Rohmer, and it’s not only because of his voice. It’s also because of his way of producing his own movies, and the economy and cost of every meal, every person on the crew, etc. He had all those things in mind, not because other people would care — absolutely not. So for the music, I cared from the start.

Filmmaker: And the original songs by Léonard Lasry?

Reybaud: In the 2000s I was writing for a blog about French chansons, so I discovered him at the time, because he was doing a lot of concerts. He was able to not reproduce, but — we are talking about money. The most expensive music was the pop music. They are completely crazy, they want dirty money. So for one song, my producer said, “We can’t afford this song.” It was a Girls Aloud song. I love Girls Aloud, and I wanted their song “I Can’t Speak French.” I don’t remember the price, but my producer said, “Maybe we can?” I said, “I don’t want to anymore.” All my desire for the song was lost when I heard the crazy amount of money they wanted. I said, “I don’t like that.” So I worked with Léonard, and I asked him, “Could you reproduce that kind of sound?” So the song is not like Girls Aloud, but he was fluid enough to use some sounds that I wanted.

Filmmaker: OK, let me ask about two specific locations. The bookstore?

Reybaud: I told you that the places are the real places. That’s for the roads and landscapes. I had to make compromises for the [interiors]. So I would say half of the [interiors] are the real places, and the other half are relocated. I hate that, but no choice — and for the bookstore, no choice, because it’s meant to be in this little town called Issoudun. This town is quite incredible: it’s a completely empty village in France. The historic center of the city is empty, and all the stores are on sale. So, of course, there has been no bookstore in this town for 40 years. So, we had to shoot that in Bourges, near Issoudon, 50 kilometers away. I showed the movie in Issoudon and in a lot of places; I wanted to show it to people where I had shot. So I showed the movie in Issoudon three or four months ago, and I couldn’t [pull the] cheat on them, because they knew. To have a real, beautiful bookshop you have to go to Bourges.

Filmmaker: And the theater where Paul goes to visit the actress?

Reybaud: It was a little theater in Paris near Pigalle. We shot the entrance in the real theater in Vierzon, so the outside is real — we went 50 kilometers just to do that shot. When my crew saw this hideous entrance, they said, “Why did you want to come here? It’s just a lousy theater.” But that’s the point, that’s Vierzon. But inside, it’s in Paris. It was impossible because the actress lives in New York. She was in Paris for 10, maybe 15 days, so she did the movie just like that, so of course she couldn’t go anywhere.

Four Days in France opens Friday, August 4 at New York’s Quad Cinema; click here for more playdates.