Back to selection

Back to selection

Shutter Angles

Conversations with DPs, directors and below-the-line crew by Matt Mulcahey

DP Rachel Morrison on Mudbound, Her Ideal Extinct Film Stock and Using Waveform Monitors

Mudbound

Mudbound In Mudbound, a friendship between two returning soldiers – one white (Garrett Hedlund) and one black (Jason Mitchell) – sets a pair of neighboring farming families on a path to tragedy in post-World War II Mississippi. For cinematographer Rachel Morrison (Fruitvale Station, the upcoming Black Panther), filmic references for the harshness of agrarian life in the Jim Crow South were few and far between considering the Hollywood studio offerings of the era were preoccupied with propagandistic war movies and opulent musicals. Instead, Morrison looked to the Depression-era photography commissioned by the Farm Security Administration – specifically the work of Gordon Parks, Arthur Rothstein, Ben Shahn and Dorothea Lange.

The result is strikingly high-contrast imagery that daringly creeps along the precipice of impenetrable inky shadows. Those images have elevated Morrison into the rarified air of Roger Deakins and Hoyte Van Hoytema – two of the fellow luminaries nominated alongside Morrison for the American Society of Cinematographers’ award for Outstanding Achievement in Cinematography. And Morrison just might hear her name as well when the Academy Award nominees are announced on January 23rd – which would make her the first woman ever nominated for a cinematography Oscar.

With Mudbound currently streaming on Netflix, Morrison spoke to Filmmaker about creating the movie’s distinctive look.

Filmmaker: In discussing the “35mm vs. 16mm vs. digital capture” camera tests that you did for Mudbound, you’ve said that the downfall of the 35mm was that the available stocks have advanced to the point where they too closely resemble digital. That made me wonder – if you could’ve Jurassic Park-ed any extinct film stocks and used them to shoot Mudbound, which would you have chosen?

Morrison: Ah, great question. I probably would have used an old EXR stock like 5298 or even the Vision 800T 5289.

Filmmaker: The film vs. digital debate typically takes the form of an aesthetic argument, but I’m interested in your thoughts on how the different formats effect the environment on set. What are the pros and cons or working in each medium?

Morrison: I do think film streamlines the process and tends to make everybody step up their game a little bit because every take counts.

- So I would say the pros of film:

- Ups everyone’s focus in the moment

- Enables intimacy and communication between director and DP

- Inherently tactile

- Eliminates having people judge off the monitor, which often leads to too many cooks in the kitchen

- Screening dailies TOGETHER

- Happy accidents

- Better handling of highlights and more natural skin tones

- Tendency to use fewer cameras or even just one, which means you can get the right eyeline and lighting without compromise

The cons of film:

- Can be cost prohibitive (depending on many factors, of course, such as how much you plan to shoot and how far the lab is, etc.)

- Labs are few and far between, so often [shooting film] involves shipping the film, which means it can be days before you see your dailies

- Not all lab technicians are as skilled these days as they once were, which can lead to inconsistencies and scratching in the processing

- You don’t get to sleep as well at night [because you don’t] know exactly what you’ve captured and you don’t know that no mags will come back scratched

The pros of digital:

- Higher ASA, so you can light with more practical lights and candles

- Camera bodies like the Alexa Mini or Red are small enough to use on a MoVI and mount in a variety of cool places

Digital aspects that are both pros and cons:

- Because media is relatively cheap, you roll more freely. This can create lazy filmmaking and too much content (con), but sometimes you get a gem of a moment that you might not have captured had you been censoring yourself (pro).

- You can see basically what you are getting [on the monitor]. It helps DPs rest well at night (pro), but also eliminates some of the “magic” of what we do and makes everyone think they are cinematographers (con). Also, [on set monitoring] can lead to too many cooks in the kitchen, because everyone has an opinion and that can cause people to focus on too many myopic details, such as a hair out of place or a wrinkle in a blouse or the curtains not being perfectly straight, instead of just focusing on the actors and performance, which is really all that matters in the end.

- More affordable often means more cameras, which is both a pro and a con. Sometimes it’s a great asset to capture two sizes of a performance (with multiple cameras in one take), but other times it leads to more compromise than it’s worth. And there’s a tendency for producers to add cameras and lose days in the shooting schedule, which will never look as good as taking your time with one camera.

Filmmaker: Mudbound has beautifully rich blacks, but I’m also interested in how you achieved the contrast in your midtones. It’s sort of the look you get when you adjust the “clarity” slider in Lightroom or the “midtone detail” setting in Resolve. How did you approach creating that look?

Morrison: I’m not very savvy in Photoshop or Lightroom, so I mainly communicate my intent to my DIT. In this case, I knew that I didn’t want the blacks to get too milked out on this film and so I made sure to expose them properly and “print down” so that we could play on the dark side but the detail would be there in the raw material if I wanted any of it back. Then in the DI, I sent [our supervising digital colorist] Joe Gawler all my references and asked him to enhance the detail whenever we needed it but not wash out the skin tones. My main reference was Gordon Park’s A Segregation Story (1956) for Life magazine.

Filmmaker: What’s your technique for determining your stop? How much do you rely on the image on a calibrated monitor versus a waveform, versus old-fashioned metering?

Morrison: I usually use my meter to light in broad strokes and then the monitor to dial things in. For example, if I know I want to expose at a T2.8 with the key side ½ stop under, I will rough in my key light to a 2/2.8split, then drop the meter and do the rest of the shaping from the monitor. On Mudbound, as I mentioned, my plan was to print down, but keep the information in the [digital] negative so my DIT Nate Borck had to keep me honest using the waveform monitor, since I was on set operating and didn’t have the IRE levels in front of me at all times.

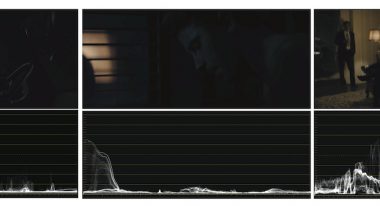

Filmmaker: I put together a few frame grabs with their respective waveform readings. Would love to hear some specifics about these shots – where did you draw the line for what was “too dark?”

Morrison: Those waveform frame grabs are from the final output (as opposed to what we were looking at on set), but if I had to guess I would say there was between ¾ -to-1 ½ more stops of additional information in the RAW material to play with. [Director] Dee Rees, Joe [Gawler] and I decided to “be bold or go home” and we did play everything dark. It’s been an interesting experience for me. When projected well, I am the happiest I’ve ever been with my work. But in a screening room with a dull projector, I am horrified. It’s hard to know if I would do anything differently next time because if I went brighter overall, I would probably be less horrified in the worst case scenarios, but also less pleased with the best version. It’s an interesting conundrum.