Back to selection

Back to selection

Shutter Angles

Conversations with DPs, directors and below-the-line crew by Matt Mulcahey

Cotton Balls, Cling Film and Unashamed Composites: DP Tristan Oliver on Isle of Dogs

Isle of Dogs

Isle of Dogs In Isle of Dogs, Wes Anderson’s Japan-set return to the world of stop motion animation, there is a character with a face full of freckles. This seemingly incidental attribute required the film’s lead puppet painter Angela Kiely to place 297 freckles on each of the puppet’s many interchangeable faces. All told, she painted over 22,000 freckles for the film. That is the painstaking diligence required for the art of stop motion animation, a form demanding an obsessive attention to minutia perfectly suited to Anderson’s fastidiousness. In a Wes Anderson film, no detail – not even a single freckle – is incidental.

“The decision process on a Wes Anderson film is very much via the director, and then it’s our job to provide the solutions for any problems that might arise,” says Isle of Dogs cinematographer Tristan Oliver, who also shot Anderson’s previous stop motion opus Fantastic Mr. Fox in 2009. “So rather than being a proactive process, it’s very much a reactive process of filmmaking [for the crew].”

In Isle of Dogs a boy named Atari searches for his pet after a breakout of dog flu finds all of Megasaki City’s canines banished to the literally named Trash Island. Though the human characters speak in frequently untranslated Japanese, the four-legged ones are voiced in English by a cast of Anderson favorites including Bill Murray, Edward Norton and Jeff Goldblum.

The film took 87 weeks to shoot – a fairly typical number for a stop motion feature according to Oliver, whose credits include Laika’s ParaNorman and a host of Aardman Studios movies. That breaks down to approximately 15 seconds of screentime per production day – and that’s with as many as 50 different sets being shot simultaneously. With the movie expanding into more theaters this weekend, Oliver gave Filmmaker a glimpse into the meticulous magic behind Isle of Dogs.

Filmmaker: What is unique about the process of making a Wes Anderson film compared to your other stop motion work?

Oliver: The biggest difference is you work from a very prescribed set of rules with Wes. You know you are going to be using very wide angle lenses, very small apertures and extreme symmetry. He also believes it’s purer to avoid some of the [technological comforts of contemporary stop motion films]. He will say, for example, “I don’t want to do this shot greenscreen,” but it’s not as if he’s a Luddite about it. If you say to him, “The only way we are going to be able to do this is if we shoot it in separate parts against green,” he will say “OK.”

Another difference in a Wes Anderson film is that everything organic is animated, which is unusual. So fire, water, rain, fog — those things tend to be made out of cotton balls, carved soap and cling film and that’s very much something we’d come away from a long time ago [on other stop motion shoots]. Even in [the 1995 Wallace and Gromit short] A Close Shave, when Gromit puts the kettle on, the gas jet that he lights is actually real gas that we shot separately and just comped in. If that was a Wes film, we would be animating blue gas flames made out of toffee wrappers or something to get that effect. So he’s quite pure about it, but in terms of VFX magic, quite a lot creeps in there.

Filmmaker: Walk me through a typical shoot day on Isle of Dogs, if there is such a thing. As on Fantastic Mr. Fox, Anderson is working remotely so you’re communicating with him throughout the day?

Oliver: In the morning there’s a traditional dailies process where we sit in a theater and look at everything we shot the previous day. That’s accompanied by a morning briefing where the 1st AD team lets the heads of departments know what the priorities are for the day. We’re typically shooting between 40 and 50 units every day, so there are 40 or 50 sets up at once and they’re all shooting simultaneously. It’s a fairly frantic process. Whenever an animator finishes a shot, that shot is immediately put into the Avid and cut into our animatic so that we can see it in context. Then that is sent to Wes and he’ll either approve it or make an adjustment, which would entail the animator going back and reanimating a portion or the entire shot. That’s an ongoing process throughout the day.

Filmmaker: The nuts and bolts of making a stop motion film are so foreign to me that I thought we’d do this interview a little differently. I’d like to just go through some frames and learn about what went into creating each image. The first shot I’d like you to talk about is Atari’s POV after crash landing on Trash Island. So we’ve got the animatic reference here and then the final frame.

Oliver: Essentially the animatic is all the storyboards put together, with each of the frames shot to the length that it eventually will be in the movie. The animatic also has indications of any camera movement or lighting changes in those frames. It acts as a gospel of sorts for the making of the movie. You don’t want to overshoot in animation, because that’s a lot of unnecessary work for the animators. So once we have the animatic locked down, it is a fairly faithful reproduction of what the film is going to look like and how it will time out.

Filmmaker: Are the storyboards in the animatic drawn with particular focal lengths in mind?

Oliver: The animatic wouldn’t specifically stipulate a focal length, but when you’re working with Wes you know it is going to be the widest possible lens we can manage, and that lens is going to be set so that we have the maximum achievable depth of field. Looking at this frame, I would say this was probably shot on a 20mm lens so we could hold both the feet and the dogs in focus at the same time.

Filmmaker: If you’re on a 20mm, the dog on the right of frame must be pretty close to the lens.

Oliver: Yeah, he is very close. Occasionally we would just run into an issue of physics [when trying to replicate the animatic]. Actually, when I say occasionally, I mean daily. (laughs) If you are working in the live action world then you can happily compose a shot like this without any real problem regarding how much focus you’ve got, because your characters are going to be three or four feet from the camera. But when your characters are three or four inches from the camera, then it’s a whole different ballgame. You’re working at the minimum focus point of the lens and the only way to get anything resembling an acceptable depth of field is to wind the aperture right down to the bottom, and even then it’s never going to be quite as good as you want. So we do occasionally split shots into planes of focus and shoot the foreground elements against greenscreen and then shoot the midground elements separately and then composite the whole lot together afterwards.

Filmmaker: When you’re shooting at an F16 or F22 to get that depth of field you’re looking for, do you have to use big light sources or can you use your shutter speed to make it more manageable?

Oliver: Just to dispel the idea that we use very tiny lights all the time, this environment that you’re looking at here is keyed with a 10K Fresnel. This shot is a bad example because there are no shadows, but typically we are trying to make realistic exteriors in animation so you need a light with a big lens because it keeps the shadows parallel rather than them spreading out, which is what you get from a smaller light. So it’s not always the intensity of the light that we need as much as the size of the light. But to your original point: yes, we can happily go to four seconds on the shutter. We tend not to work any longer than that, just because it’s a hell of a long time to wait. We typically work between a quarter of a second and two seconds for shutter speed.

Filmmaker: Did you stick to one ISO on the Canon 1DX’s you shot with or did you jump around?

Oliver: My 1st AC Mark Swaffield did a huge amount of Googling to find out what everyone thought the optimum ISO of the camera was, because everyone has a different opinion. Some people said 100 and then others said 160 or 200. In the end we went with 100, which seemed to work perfectly well. We didn’t need a very sensitive chip because we could adjust the shutter speed. And we got a very large, full frame RAW image from those cameras, which we could then play with [in post] until our heart’s content.

Filmmaker: Since we’re looking at a shot with the hero dogs in it, tell me about the challenges of lighting and shooting the fur.

Oliver: Hair does have a number of problems innately. If you’re shooting against greenscreen and anything is even slightly out of focus it’s very difficult to pull a key off. The other thing is the filamentous nature of fur does cause quite a bit of refraction. If you look at some of the close-ups in the movie you will see that you get this sort of magenta/pink blooming on some of the fur, which is due to the light refracting through the hair. Chief occasionally looks a bit purple for that very reason, even though he’s black.

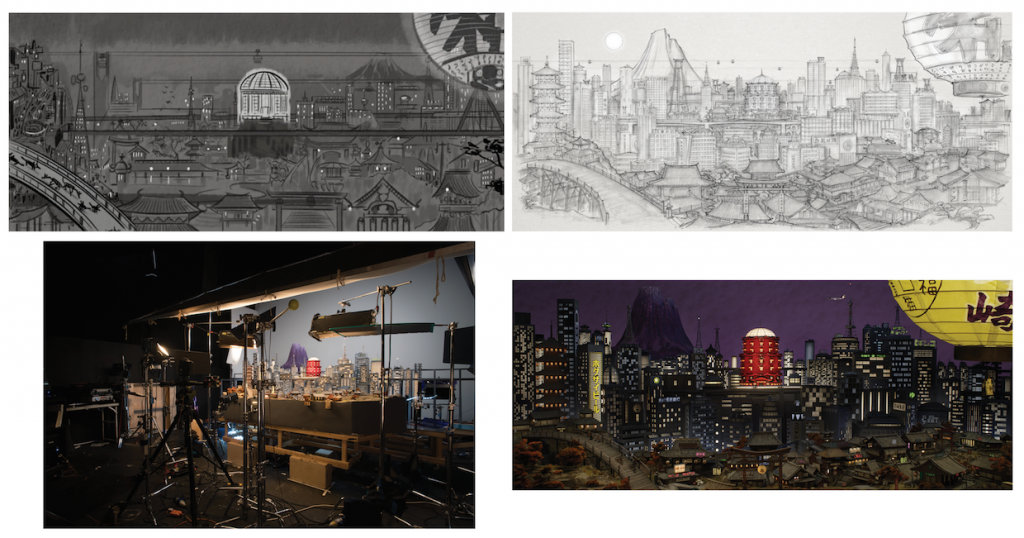

Filmmaker: The next set of frames shows a few of the steps in putting together Megasaki City.

Oliver: This is a typical layout for us. We go from animatic to what is essentially an architect’s drawing, which is then properly drafted into an actual architectural plan and then from that the set is made. This particular set of Megasaki City is entirely modular. Every one of the buildings has a magnet in the base and sits on a steel plate so that they can all be rearranged in an infinite number of ways. There are shots of Megasaki City all the way through the movie and it always looks slightly different because it’s from a different viewpoint. So we had multiple iterations of building layouts and multiple iterations of times of day, sky color and things like that. We shot many different offerings of what the lighting was like. We shot it with a hard key, daylight, high key, night time, and then various softnesses all the way through to completely flat, shadowless lighting, which tended to be what was favored on this movie. Then we’d do every conceivable combination of lights on and lights off inside the buildings. This final image you see is probably a combination of a number of different exposures which have been put together in the postproduction process.

Filmmaker: Did you do that sort of exposure bracketing for a lot of scenes?

Oliver: That is something that kind of dominated the movie, really, and it is very much one of the things that is bad about digital capture, especially for animation, which is you can take an infinite number of variations of each frame and that throws the decision process of how something looks to the end of the movie. Although we didn’t do a huge amount of deciding what the lighting would look like [in post], we did do a lot of that in terms of lighting effects. For instance, if there was a lightning flash, we would shoot that lightning flash on every single frame of the shot and then obviously we’d shoot every frame without [the effect]. That way we could time the lightning flash to go anywhere we’d like. So it takes some of the organic creativity out because everything is constantly being thrown to the backend of the process, which is quite frustrating.

Also, because we were never entirely sure whether Wes would come back wanting additional detail in the background, we would quite often shoot exteriors against the designated sky, and then we would wheel in a greenscreen background and retake the exposure, so that in our back pocket we had a greenscreen pass that we could use if it was later decided that the background should be different.

Filmmaker: I’ve only done one other interview with the DP of a stop motion film and that was for Anomalisa. They used this software, Dragonframe, on that movie. Is that something you use as well?

Oliver: We did use Dragonframe. It’s become industry standard and quite rightly so. What Dragonframe does is integrate everything you need into one piece of software. So I have a cinematography page on Dragonframe that gives me control over the camera. I have a DMX page that gives me full programmable control over lighting channels. There’s an animation page where the animator can review their animation and also keep an eye on their lip sync. There is a motion control page that enables me to set up simple motion control moves. That whole lot all runs on the same timeline, so whatever you do on any one page is ready to go in all the other pages. So if I make a lighting adjustment on the DMX page, I know that when the animator hits the appropriate frame [the software] will initiate the lighting change regardless of which page Dragonframe has open. It has radically changed what we do and it makes life for the animator much easier, because all they have to do is press one button and everything happens at the right time and in the right way.

Filmmaker: When I was doing research I was surprised to find out that once everything is set, all the crew clears out and the animator pretty much works on the stage alone.

Oliver: Animators like to be left alone. Once the set is dressed, lit, painted and propped and the motion control is set up, when everything is absolutely ready and approved, the crew moves on and the animator goes in and does the shot. So the crew is constantly moving through the different spaces, setting shots up and striking stuff out. It’s a very busy environment with a couple of hundred people moving through it, but then on the sets where animation is actively taking place there’s sort of a zen-like calm as the animator carries on with their trade.

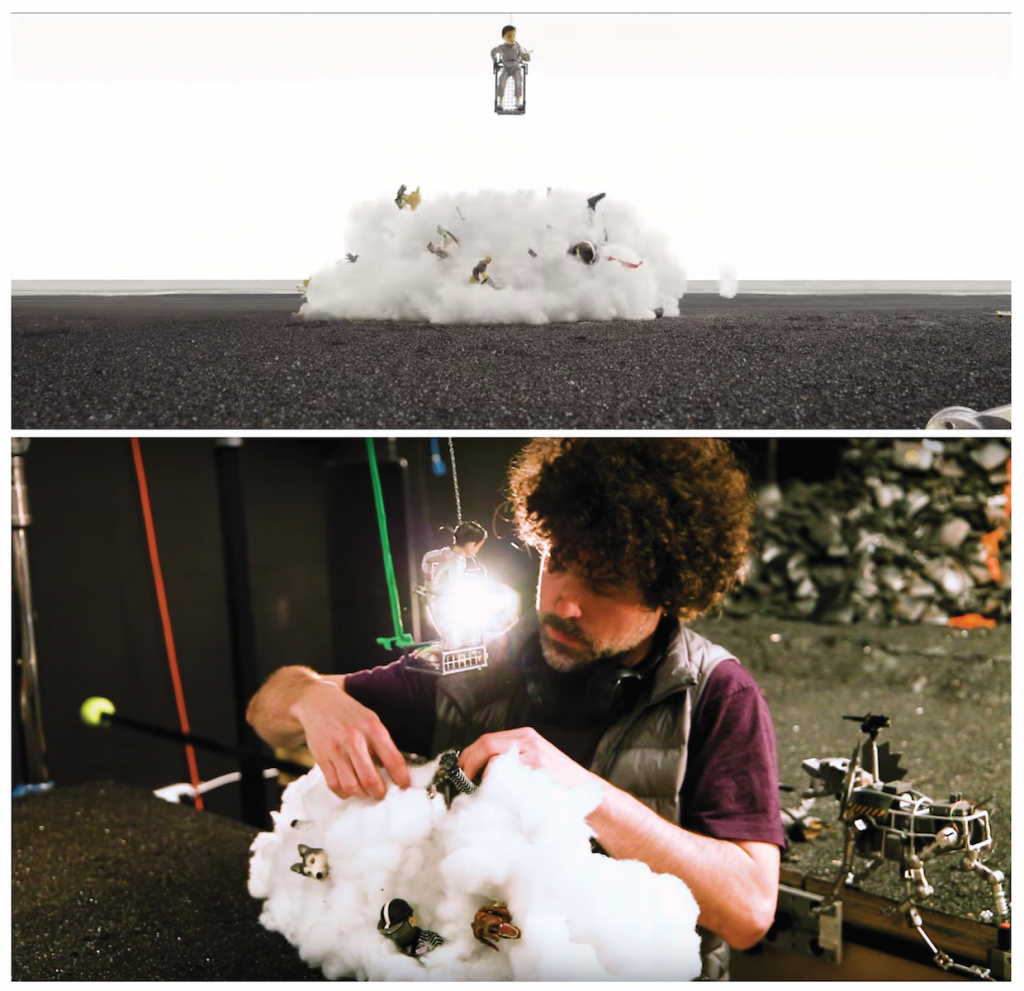

Filmmaker: One of my favorite bits in the movie are these big dust balls that happen whenever the characters become embroiled in a brawl.

Oliver: What you can’t see in these photos is what’s inside that cotton ball cloud, which is a fearsome amount of engineering. There’s a huge amount of steel and brass armature and ball-and-socket joints, a bit like a mechanical spider, that sits inside that ball. On the end of each of those spider arms is a dog’s head or leg. That armature gives it structural stability, so the animator can essentially position those pieces of dog in space.

Filmmaker: Was it hard to light the cotton balls and not blow out the detail?

Oliver: White is always a problem, especially when you’re in a black environment. So we mostly backlit [the cloud], but it’s backlit with multiple sources so that the armature that I’ve just described isn’t causing too many disruptive shadows. If it were just lit by one light you’d actually get the projected image of the spidery armature on the cotton balls.

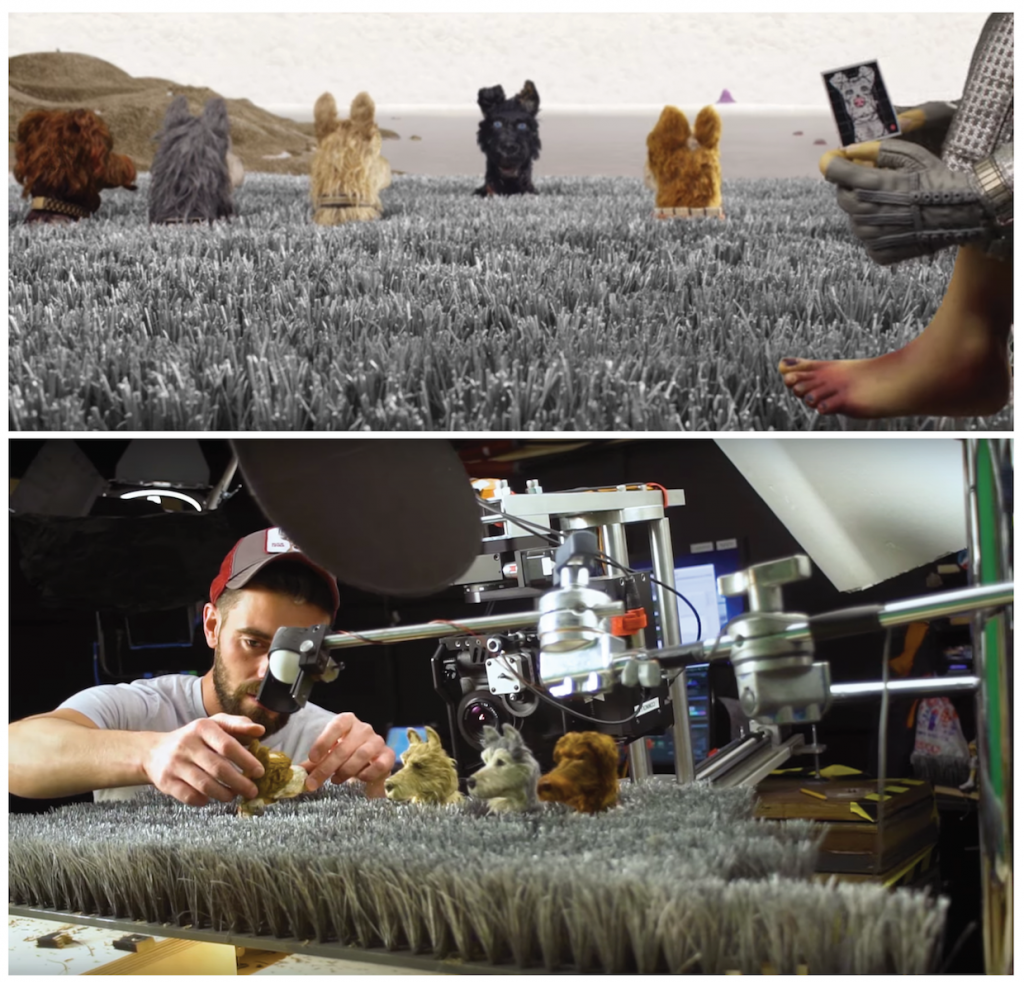

Filmmaker: The reason I pulled this next set-up is because I read that you used little LED bulbs inside ping pong balls as eye lights for the dogs. Is that one of those ping pong ball lights I see in the clamp here?

Oliver: Exactly. We used what we call Power LEDs, which are super bright, and then we used the ping pong ball as a diffuser so that the light is not quite so fierce, because a point source like that gives a very hard shadow. But the great thing about LEDs is that they are quite cool in temperature and they weigh almost nothing, so they can be rigged very easily. This was a particularly complicated shot because it had to be photographed in various layers. All those grass elements [in the foreground] were shot separately because, as you can see [in the behind the scenes photo, there’s not really much space between the camera and the dogs. So all those layers of grass were shot as separate elements to give that depth.

Filmmaker: How different were the units you used to light Isle of Dogs compared to Fantastic Mr. Fox? It’s only been seven or eight years between the movies, but all these little LED bulbs weren’t really being used then.

Oliver: There was a sort of sea change about five years ago when I went onto ParaNorman. That was the first job where LEDs became feasible for us, because the color temperature for them finally got sorted out. Prior to that LEDs were the most disgusting color and you’d end up putting so much gel on them — loads of minus this and plus that — just to get them anywhere near a usable color. All the advantages of using them disappeared, because you had to cover them with so much tape and gel that they became impractical, and we already had small incandescent fixtures which were doing the job perfectly well. But what we now have is very small, color true LED sources, and the great thing about them is that they are infinitesimally small and you can dim them without the color temperature changing. Also, because of their physical size, we’re able to make very long strips of LEDs that are very soft sources. For a lot of the night time stuff we’ve gone over to using these seven- or eight-foot long LED strips placed very high up over the set, and they give this rather nice diffuse glow that looks like a big softlight. However, we still use incandescent fixtures. In fact, in the Municpal Dome all those Japanese lanterns are actually lit with incandescent bulbs dimmed down, because when you dim a tungsten incandescent fixture it gives a very nice warm glow.

Filmmaker: The next frame is a showdown between Atari and a band of canine robot henchmen. I read that on Fantastic Mr. Fox, Wes Anderson wasn’t thrilled about the idea of using greenscreen. Was he more flexible this time around?

Oliver: Well, it’s a nice thing to say that we never use greenscreen but in actual fact we use quite a lot of it. (laughs) We used some of it on Fantastic Mr. Fox as well, but Fox was a much simpler movie. For something like this shot — this set is quite large if you look at it. It’s all constructed out of welded steel, and to make this set the size that it appears to be in the movie would’ve been practically impossible. The only way to make the shot work is to shoot it as greenscreen elements, then combine the elements together, then put the background in afterward. If you shot the background practically, it would be so vast that it would take up a huge amount of studio space. So this shot is unashamedly composited.

Filmmaker: Let’s do this overhead tracking shot next.

Oliver: This is also a composite. The cliff face and the surface were shot on a set that was about four feet high with a fake perspective on it, so that great sense of height is entirely fake. The trucks are a separate element that have been composited in. The dogs and Atari are also a separate element, because they would’ve been absolutely ant sized if they were shot practically in this frame and would’ve been impossible to animate. So the boy and the dogs were shot walking on green and then composited in.

Filmmaker: I read that you had four or five sizes of these hero characters, but you ultimately used almost one size exclusively.

Oliver: We did have about five, but there was something about the way the fur worked on the smaller sized dogs that made them look just a little bit puppy-ish, and that didn’t really work for us. It was impossible to scale the diameter of the fur filament for those smaller dogs. So we either used the big dogs up close or the small dogs further away.

Filmmaker: Let’s finish up with this silhouette shot. How do you create the effect of moving water?

Oliver: The water is done with our old favorite “cling film,” which is your classic plastic sandwich wrapping. We used miles and miles of it. It’s often just laid onto glass and you can create the sense of the water moving just by moving light across it. There’s a shot where [Atari and the dogs] are shot out of a sewer pipe. For that, we had a vast conveyer belt of cling film that was about twenty feet long, which was running on rollers in order to give the sense of it receding.

Atari standing on the dog was originally just shot on green as a completely clean silhouette. Then these foreground elements were constructed much later, because the design of this scene hadn’t really been established [when we shot Atari]. Those are just two large polystyrene blocks that have been painted and behind them is a sheet of glass that is laid at an angle. That sheet of glass had cling film on it and then under that cling film was green. So you could see chroma key green through the cling film, because we weren’t sure what color any of this was going to be when we shot it. The volcano was a separate element and the sky was green. So all that orange that you see in this shot is a post grading effect.

Matt Mulcahey works as a DIT in the Midwest. He also writes about film on his blog Deep Fried Movies.