Back to selection

Back to selection

The Cine-Ghosts of Shirkers

Some of my best conversations have been with people who weren’t there. Absent was OK—even nonexistent was OK. As long as I imagined somebody was there. I did that as a prolific letter writer, I did that as a novelist, and most recently, I did that as a filmmaker.

More than 20 years after the defining trainwreck of my youth—having my teacher/mentor disappear with all the footage of a 16mm film we’d shot together—I decided to make a film that would both document the joys and perils of teenage creativity and unfurl the detective work behind the mystery of the vanished film once and for all. Editing Shirkers during 2017, I found myself in another one-way correspondence—this time with Georges Cardona, the film thief himself. My nemesis still had things to say.

Georges was a man short on truth and long on fiction. He might still be the best storyteller of his own life that I ever met. Rather than give away spoilers to my film, I’ll say here that he was a true vampire of cinema, living his life as an ongoing collage of his favorite films, mimicking the smiles and gestures of performances he admired (Jean-Paul Belmondo in Breathless, Ben Gazzara in Saint Jack, Jean-Claude Brialy in Claire’s Knee) and lifting questionable plotlines from certain films (the mind games of Claire’s Knee, say) as actual Things To Do.

As a child who’d grown up in repressive 1980s Singapore, reading about David Lynch and Cronenberg in American Film and Film Comment and memorizing synopses of movies that were impossible to see, I was used to relying on my imagination. Georges’ appearance on the scene in 1991 therefore seemed like a veritable Inciting Incident. Here was a Francophile American (with a strong Latin accent) in his 40s (“late 30s” as he’d put it) who had not only seen all these elusive movies but could describe the sensation of watching them from beginning to end.

At the time, I was dawdling in that gap between high school and college, interning as a kid movie critic at Singapore’s largest daily broadsheet. The minute I walked into Georges’ 16mm filmmaking class at the Substation arts center, I couldn’t help but think that this unlikely intersection of our paths was—as someone who also applied movie tropes to life—kismet.

Like Jasmine and Sophie, my fellow 18 year olds in the class, Georges was a teenage girl. By this, I mean temperamentally he was one of us—giggly, impulsive, paranoid—and he joined our clique. Almost to prove this synchronicity, the first assignment he gave the class (made up mostly of media professionals in their 30s) was to go see a meandering Éric Rohmer comedy about two young women in Paris: Four Adventures of Reinette and Mirabelle.

I never cared that Georges was a “filmmaker” who’d never written a script or made a movie. I missed clue number one when he named the short film our class made I Have Never Told The Truth. His own life, the way he talked about it, with its spilled blood and derring-do, was its own Werner Herzog epic. So, when I handed him the unclassifiable screenplay I wrote in the spring of 1992, combining my obsessions of the day—murder, memory, road movies, 1950s production design, the freewheeling spirit of the French New Wave—of course he insisted we had to shoot it.

I called it Shirkers, and I played the lead, a 16-year-old killer named S. We assembled a ragtag crew of kids (Sophie produced; Jasmine was AD), and Georges contributed his ideas: the “magic hour” cinematography of his idols Robby Müller and Néstor Almendros, and what I would later discover was mise-en-scène foraged from movies he’d loved in his youth. His memories, it turned out, were movie memories.

Twenty-five years after shooting the original Shirkers on the streets of Singapore, I tried to reanimate my strange foe in my Pasadena garage/studio using the ghostly cinematic breadcrumbs he’d left me. I’ve kept the largest pieces in Shirkers, but there were casualties as I sheared down fuzzy edges to shape the film in its sleek 96-minute form.

This list of the cine-ghosts that got away is essentially the DVD extra I’ll never get to have (because, well, Netflix owns Shirkers).

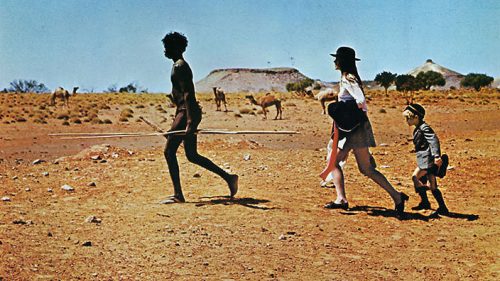

1—Walkabout (1971, Dir: Nicolas Roeg)

Shirkers (1992) took more than two months to shoot because Singapore’s equatorial light was so flat and harsh that Georges decided the solution would be to shoot exteriors only during magic hour—which on the equator lasts 15 minutes, at best. Georges was obsessed with Nicolas Roeg’s surreal Australian Outback road movie Walkabout for reasons I couldn’t understand. (Much later, I surmised it was probably as much Jenny Agutter in, and out of, her school uniform, as it was his admiration for DP/director Roeg.) We spent countless days in unusual locations, walking.

2—Alice in the Cities

(1974, Dir: Wim Wenders)

Georges idolized Dutch DP Robby Müller for his work on Wenders’s Paris, Texas and on this road movie shot on grainy, black-and-white 16mm, movies I found boring when I first saw them via fuzzy VHS on a small TV. Above all, I couldn’t get past the low-key, anti-charismatic lead performance by AITC’s Rüdiger Vogler, not realizing I’d soon be guilty of similar nonacting acting in Shirkers. Revisiting AITC decades later, I saw other uncanny visual symmetries.

3—Claire’s Knee (1970, Dir: Éric Rohmer)

Georges worshiped DP Néstor Almendros not just for his natural-light artistry but also because he was a Hispanic (like himself) who’d transcended borders and worked with the greats—Rohmer, Truffaut, and Malick. (I think the famed locust-swarm trick in Days of Heaven was Almendros’ idea.) Bathed in Almendros’s offhand, naturalistic style, the casual cruelty of Claire’s Knee is all the more unnerving: A middle-aged man (played by Jean-Claude Brialy) spends his summer vacation toying with the affections of two teenage girls, with his personal goal of touching one of their knees being much more psychologically twisted than any conventional conquest. Georges modeled himself on Brialy.

4—The Green Room

(1978, Dir: François Truffaut)

Almendros also shot this rarely seen, barely loved late Truffaut film about a man (played by Truffaut, inertly) who keeps a room in his house for his wife who’d died 10 years before—essentially a ghost story about obsession (and based on the Henry James short story “The Altar of the Dead”). Georges had often talked to me about this obscure film, but it was only after I saw it 25 years later that I realized he’d stolen this scenario for his own life: For years, he kept the 16mm canisters of Shirkers in their own room in his home, as if they were a living, breathing captive whose loss was a black hole in the lives of others.

What Georges Cardona did to Shirkers and the teenage girls he befriended in the early 1990s was ultimately stranger than any fiction he (or I) could have dreamed up. It was only after making a film about it that I have finally explained the past 25 years of my life to myself. The process of filmmaking helped, yes, but the act of viewing even more. I suspect you would understand. To me, to Georges, and to the bleary-eyed regiment who read this magazine, it may always be truest to say we are less what we eat than we are what we watch.