Back to selection

Back to selection

Seamless Transitions: Remembering Stanley Donen

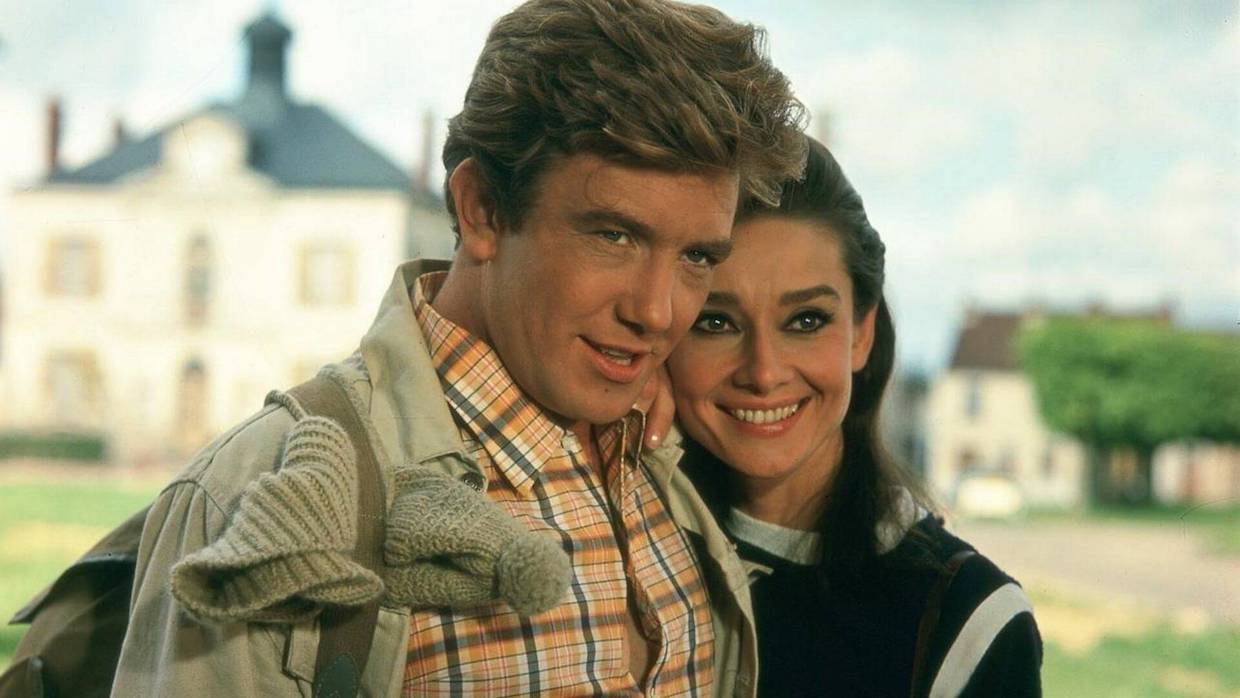

Albert Finney and Audrey Hepburn in Two For the Road

Albert Finney and Audrey Hepburn in Two For the Road In 2003, I was at Columbia University getting a masters degree in film and television. A friend who had just graduated called me with a rather unusual offer. Stanley Donen—the prolific and award-winning director of Singin’ in the Rain and Seven Brides for Seven Brothers, who died this February at age 94—was looking for a producer. My friend had been talking to him about taking the job, but when Stanley found out he would be graduating in a few months, he asked him to find someone who was still a student. “It’s a student film,” he said. I didn’t get it. I asked him to repeat himself. “It’s a feature, but he wants it produced entirely by students.” He gave me Stanley’s address, and I was set to meet him the following week. He also sent me a script to read called Bye Bye Blues.

At the time, I was obsessed with a book titled The Genius of the System about the studio system and why it was so effective at the peak of its existence. But I never thought I would meet one of the legendary filmmakers who came out of that system, which had all but disappeared by the early 1960s. In 2003, there were already very few studio directors living, and none were easily accessible to a film student in New York City.

Of course, he codirected Singin’ in the Rain with the movie’s star, Gene Kelly, and has now gone to his grave, as did Kelly, without mentioning publicly who designed and directed Kelly’s famous umbrella dance. But I was always slightly more fascinated by some of his other musicals, especially Seven Brides for Seven Brothers. There was something about the energy of that movie, the eloquence of the musical sequences that should place it among the best musicals of all time.

But of all his dozens of films, the one that most moved me was his nonmusical drama Two for the Road. Albert Finney and Audrey Hepburn played a couple traveling through Europe, five trips at five different times in their lives. The time periods folded over and into each other. The young version of the couple might be hitchhiking, madly in love, when a convertible would bomb by them in the opposite direction, with the older version of the couple fighting over the disintegration of their marriage. Only as the movie progressed did you discover what had taken this perfect couple to the brink of destruction. It felt like both an experimental movie and a more realistic analysis of memory and place than anything I had seen. And as I get older, the movie only gets more profound.

Needless to say, I was nervous to meet him. He was 78 at that time, and the last movie he had made was Blame It on Rio in 1984, but he was still the legendary director of Charade, Bedazzled, Damn Yankees and Funny Face. The address was a Central Park apartment. It was meticulously clean and ordered with shelves tastefully peppered with memories of his treasured past. I later learned this was his office and the apartment where he lived was blocks further north, also on Central Park. In his living room, he looked the part of a living legend. He wore tinted glasses, his eyes barely perceptible behind them. He had a gray beard, perfectly trimmed. And he wore a turtleneck with a gold chain with what looked like a dog tag. It turned out it was a dog tag that read “If lost please return to Elaine May,” the brilliant comedian, actress, screenwriter and director, and also his girlfriend. He still had a slight southern drawl, a vestige from his childhood in South Carolina.

The script that had been sent to me, Bye Bye Blues, told the story of an aging director who couldn’t get his next movie made because he had, in the eyes of the industry, become long in the tooth. The movie within the movie that this director was trying to make was a musical about an architect who only wants to build beautiful buildings where the world only wants to focus on the bottom-line profits. He eventually falls in love with a junkie and prostitute and ends up at the end of the movie singing an old standard called “Bye Bye Blues” as he overdoses on heroin. Not surprisingly, no one wants to let the old director make the movie. But the story takes place in the early 2000s, when digital was changing the industry. So, the director decides to make it for no money, using a group of passionate film students and casting himself as the lead. He eventually convinces Harvey Weinstein (with the obvious context that it was at the peak of his power as Miramax indie broker) to distribute the film. But Harvey has one condition: The director will have to actually overdose and die in the movie. With that, Harvey thinks he will have enough of a marketing angle. (They had pegged him a sadist even then).

It was an outrageous premise, but written as it was by Elaine May, the script was funny as hell, engaging and surprisingly moving. Its parallels to Stanley Donen were not hard to find: To drive home his critique of Hollywood a bit further, Stanley had decided to play the role of the aging director himself. And he was enlisting a student producer because he wanted to actually make the movie with a film school student crew. It was as meta as facing two mirrors toward each other and creating an infinity of images.

In his office on Central Park, he explained this all to me, smart enough to know that any film student with half a brain would bend over backwards to make this happen. I promised him I would do whatever possible to help bring this film to fruition. I immediately went about the task of running budgets and trying to raise money using my very thin address book of wealthy friends, family and industry contacts.

Every month, Stanley would call me and ask to have lunch. I would give him updates, show him budgets and schedules and educate him on the digital equipment that was coming out and the movies made on them. Before long, Stanley and I had become friends, and with that friendship came a treasure trove of stories. He would tell me about playing chess every Sunday with Humphrey Bogart or playing pranks on Frank Sinatra on the set of On the Town.

While Stanley’s movies were all heart and feeling, Stanley himself could be pretty difficult. He didn’t suffer fools. I saw him dress down waiters and others who crossed his path. He had forged a career, first as a studio director and then as an independent filmmaker after the collapse of the studio system, on sheer willpower. He was irreverent and anti-establishment and tough as hell.

Once we were meeting with a potential financier, the son of a famous fashion designer. It clearly irked Stanley that this producer was using his father’s money to buy his way into the business. As this producer was rattling off his credits and experience, Stanley interrupted him and said, “This is a low-budget movie; producer has to do everything. Are you going to lug cables and drive the trucks like Ben?” Our money walked swiftly out the door—and I had no idea I would be lugging cables until then.

I did not escape unscathed from Stanley’s sometimes prickly personality. On one particular occasion he had asked me to arrange a casting session for the actors who would play the students in the movie. Despite not having a single penny raised, I figured no one would say no to doing this for Stanley. I called up a well-respected casting director who I vaguely knew, got a buddy to help video the audition and organized and scheduled everything. I was so eager to show Stanley how competent I was that I was soaking in flop sweat by the end of the day, but everything went without a hitch. As the day was winding down, he called me into the other room. I knew what was coming, which was exactly what I wanted and needed from Stanley: his praise for a job well done. He sat me down, looked me deep in the eyes and said: “Ben, you stink. You need to find a better deodorant.”

We never did get Bye Bye Blues made. I ended up working with him for nearly five years, long after I graduated from film school. Every week, some journalist who wanted to write about musicals or Stanley’s career would call, but no one was calling to finance his movies. He once got so frustrated, he jumped up from his seat and said, “I can’t take this anymore, I’m going to call Steven.” “Steven who?” I asked. “Is there more than one?” he asked rhetorically. He got Spielberg right on the phone and within an hour the head of a studio was calling and the script was sent. We never heard from that studio again.

Finally, after many lunches and budgets and failed conversations with investors, I moved out of New York to start a job at a production company. Before I left, I called Stanley to say goodbye. He told me that he could not let me leave without paying me for all the work I did. I said that a signed poster from Seven Brides for Seven Brothers would more than suffice. It reads, “To Ben, in gratitude, respect, admiration and friendship. Stanley,” and I cherish it.

Some years later, I was producing a musical. We were discussing whether or not we should record the singing live or in studio. There was much to consider. I decided I would call Stanley to walk through our problems. When I explained to him I was producing a musical he perked right up. But when he realized I had already hired another director, he used some choice words and hung up on me. He was 86 at the time. It didn’t offend me that he was angry; it amazed me that he still had the fight in him to make another movie, and every time the phone rang he had some hope that the call was for a gig.

A few years back, I ran into his son, Josh Donen, a once-powerful CAA agent and now successful producer, and mentioned my time with Stanley. He had been Stanley’s agent when I was working for him, remembered me and thanked me for helping his dad. I told him it had been one of the great joys of my life. I learned from Josh that Stanley’s health was not good and that, I thought, probably explained the last call we had together. Either way, I always knew that a man who could create such joyful movies had, underneath that hard exterior, a beautiful soul. That’s how I will always remember him.

During one of our lunches, I asked Stanley what the most difficult thing was about directing musicals. He talked a bit about how the camera must dance like its subjects and how wide continuous shots were always more powerful than quick cuts to truly capture dance. But the most difficult thing, he explained, were transitions: how a character goes from the normal world to the singing one. The more seamless that transition, the more natural and organic, the better. Nothing exemplifies that transition better than Kelly singing in the rain. But it’s a transition Stanley pulled off so many times, in so many movies, always so seamlessly and with such artistic grace.

Which is how I imagine his transition from this world to the next.