Back to selection

Back to selection

“Opening Up a Space Where the Questioning of Power is Normalized Instead of Invisibilized”: Discussing the 2019 Camden International Festival

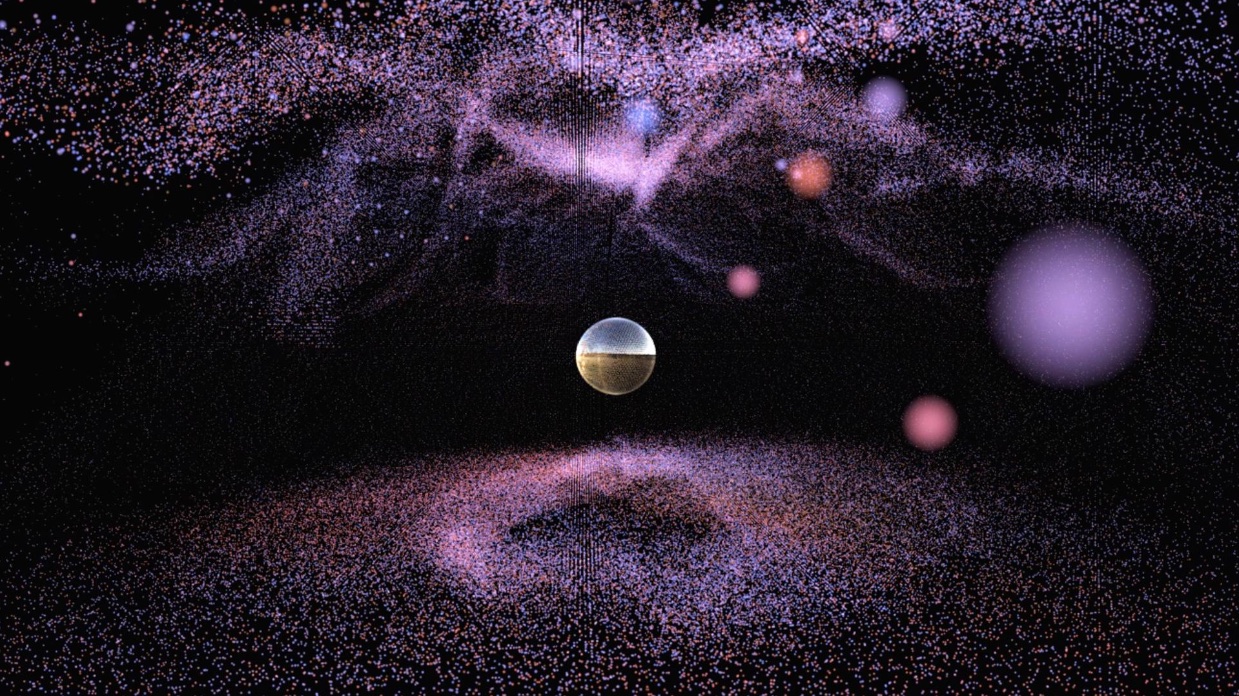

Lux Sine

Lux Sine “Who is this film made for, in what way is power present, how does the film understand its relationship to its subjects, and who benefits from the film being made?”

That’s Samara Chadwick, Senior Programmer at the Camden International Film Festival, on this 2019 edition’s theme of “Story and Power.” But if you’re attending the festival, don’t look for this theme to be a didactic one, she says. “It’s less a series of affirmations and arrival points and more about the process of questioning — opening up a space where the questioning of power is normalized instead of invisibilized.”

The Camden International Film Festival begins today and lasts a weekend, running through Sunday, September 15. And while an exploration of “story and power” may be most visibly present in the discussions occurring at the festival’s concurrent Points North Forum, the focus on power dynamics was perhaps most significantly applied behind the scenes. Ben Fowlie (Executive and Artistic Director and Cofounder), Sean Flynn (Program Director and Cofounder) and Chadwick reveal that over half the selections at Camden this year were programmed from the festival’s online submissions platform. Thirty volunteers worked with the programming committee and the more specific language regarding festival criteria was developed as a group, says Chadwick. The larger selection pool, full of films from filmmakers of different backgrounds targeting different audiences, was “humbling,” she says, noting that the selection process this year raised questions of about the different identities of doc audiences that then informed the programming of a slate that contains eight world premieres and selections from 35 countries.

Films in the program specifically speaking to the power theme are three pictures — Sung-A Yoon’s Overseas, Lauren Greenfield’s opening night The Kingmaker, and Alexander A. Mora’s The Nightcrawlers — that, says Fowlie, “explore the many angles of the former US colony of the Philippines, and encounter all sorts of counternarratives beyond the headlines, and beyond our common (mis)understanding of history and of power.”

Continues Flynn in an email, “We have many works that interrogate racial identity and power, in explorations of how new documentary forms might expand our capacities to talk about and confront racial injustice. We see this for instance in Ja’Tovia Gary’s The Giverny Document (Single Channel), and this theme also carries over into the Storyforms Immersive Program with projects like Whitney Dow’s Whiteness Project.”

Another theme evinced by the programming: films visibly imprinted by their productions. Says Chadwick, “Many films in this year’s program were tangibly transformed by the process of production — they are works that seemingly set out to tell a specific story and allowed themselves to be completely rerouted by the people and the processes of the shoot. These are tributes to the value of patient observation and active listening, to gorgeous cinematography, and to reimagining new forms of narrative beyond conventional western tropes.” She cites Mary Jiménez and Bénédicte Liénard’s By the Name of Tania, Sam Ellison’s Cheche Lavi, Vytautas Puidokas’s El Padre Medico, Elke Margarete’s Lehrenkrauss’s Lovemobile and Ezequiel Yanco’s La Vida En Comun as examples here.

“Doc filmmakers are five to seven years ahead of where the public is,” continues Fowlie. “As we evolve as a curating team, we are getting better on how works speaks to one another. We’re not just creating films but a program — where one film ends, another picks up.”

The above list of films contains a healthy number of discoveries and world premieres, but Camden remains a place where the fall’s doc heavy hitters — this year films like American Factory and For Sama — screen on their way to broader recognition. “September and October are ridiculous and hectic months,” says Fowlie. “We’re constantly trying to balance being a place where we can highlight new work but also showcase gems of the festival circuit while staying rooted as a community event. It’s taken us over a decade to carve out this small weekend in September, and the [exhibition] windows are working for us and we have built relationships that are paying off.”

With the documentary field, per Flynn, becoming “bigger and more robust, with bigger producers getting involved and a little more Hollywood and Silicon Valley, there’s a need for organizations like ours. As things get more centralized around the major platforms, there’s a need for the work we do — pulling [new filmmakers] into the mix.”

One area of the program where the critical focus on power dynamics is found in not just content but form is the Storyforms new media section. “Immersive and VR provides a different way of opening up these questions,” says Flynn. “These creative experiences in the virtual world give people agency and allow them to reach a different kind of understanding.” Through their ability to present multiple points of view, continues Chadwick, these works “allow the viewer to understand conflicting histories.” Relevant examples cited include Alex Suber’s Lux Sine, which spans locations including the Black Hills of South Dakota and a particle physics lab in order to explore the origin story of the Lakota Tribe. Because it’s a relatively longer piece at 15 minutes, “it lets you get into this deeper, more meditative space,” says Flynn.

At 30 minutes, Darren Emerson’s Common Ground is the “longest piece [Storyforms] has ever done,” says Flynn. The work is about London’s Aylesbury Estate and explores the history and legacy of social housing in the UK. And then there’s the festival’s work with Dow, whose Whiteness Project “examines both the concept of whiteness and how those who identify as ‘white’ or partially white process their racial identity” and will screen in an installation version as well as in a partner gallery after the festival in which the voices of Maine residents will be added to the ongoing work.