Back to selection

Back to selection

TIFF 2019, Last Days: Uncut Gems, Atlantis, Jallikattu, This Action Lies

This Action Lies

This Action Lies At Marriage Story‘s TIFF premiere, the audience applauded the Netflix logo; a night later, the same happened for A24 at Uncut Gems. The latter makes slightly more sense—rightly or wrongly (no comment), A24 has coherent brand cachet in positioning itself as Art-Fixated rather than purely profit-motivated—but in both cases I felt like I was going mad, and even more so when I heard that the first question for The Lighthouse‘s cast and crew at their first screening was why is A24 is so very special (surely that’s not on Willem Dafoe to answer.) Admittedly, Adam Sandler shaking Kevin Garnett’s hand onstage after both were intro’d by Josh Safdie is peak 2019 the-algorithm’s-gone-wonky, but for sheer weirdness logo-mania that can’t be explained merely by company employees in the audience left more of a mark.

As at any large festival, the pervasive shaping undercurrent of money is everywhere. There are the screening venues’ names (it’s not the Princess of Wales Theatre, it’s the Visa Screening Room at the Princess of Wales Theatre), the little-loved sponsor bumpers, the nearby street of booths set up to tempt the idle or curious—this year, festival-goers and passers-by could e.g. stand in line for a free bag of Lyft-branded popcorn, which I absolutely saw people then Instagramming. From the press side TIFF is easy to navigate—overstuffed with big catch-up titles, invariably with some deep cuts paying off—and therefore hard to get too annoyed with. If I were a member of the public, I’m not sure I’d be so sanguine—occasionally I’d look down at one of the tickets I’d gotten for a public screening and wince at the price. In any case, the festival provides some of its escape options from the money fueling it: I began my festival with Angela Schanelac’s I Was at Home, But… and concluded it with a 35mm rewatch of Pickpocket she introduced—free, open to the public, a very cool bonus note to end on.

The Safdies’ even more frenzied companion piece to Good Time, Uncut Gems initially seems to be operating in the same mode on a conspicuously more expansive scale—establishing that is the primary purpose of its otherwise kind of unnecessary (but still impressive, as desired) Ethiopia-set prologue, with dozens of extras wandering through mines. Daniel Lopatin’s excellent score kicks in immediately and rarely recedes across 130 minutes, which quickly link the site of diamond production (via an impressive, elaborately disgusting transition I won’t spoil) to one recipient of its labor, jewel dealer Howard Ratner (Adam Sandler). Both this and Good Time begin in chaos, adding twists at rapid speed, with each new problem that needs to be solved creating another three ramifications—the ante keeps being upped, but in Good Time the wistful goal was to hopefully get back to some kind of stability. It took me a while to realize that Gems doesn’t work that way: Ratner’s life is always adrenaline-junkie chaos, so what we’re seeing is the illusion of constant spiraling action (both sonically and visually) that’s actually much closer to the stasis of cyclical failure than is immediately obvious.

The meta-casting of Sandler by the obviously sports-obsssesed Safdies is very on-point—it’s rumored that Sandler has a satellite dish and large TV that travel with him on-set so he never misses a big game, which presumably explains why the shoddy likes of Grown Ups end up costing $80 million (all those scheduling overruns), so a film that significantly pivots on long scenes of Sandler yelling at the screen as the NBA Playoffs unfold is presumably as much documentary as construct. The Safdies’ desire to make an old-school NYC movie is of course itself mediated by money—it’s a lot easier to work up nostalgia for Diamond District hustle if you can afford the real estate around there—which is not a problem, just something to note. Overstuffed on every level—a bonkers cast where top-billing Sandler and Garnett is just the tip of a deeply weird ensemble, the restless pairing of Darius Khondji’s moving camera and Lopatin’s brass-y, will-not-be-ignored-score, its 130 minute running time—Uncut Gems is definitely not boring, but it’s a lot, more than I can comfortably handle.

I was immediately at home, almost suspiciously so, with Valentin Vasyanovich’s Atlantis, a textbook Festival Film that reminded me why these can still be exciting. I’d run across Vasyanovich’s name (he’s also the DP of The Tribe) in an intriguing Michael Sicinski piece surveying the kind of seeming festival filler only seen by super-diligent trade reviewers, which described his third feature, Black Level, as “eerily familiar […] a little Ulrich Seidl here, a little Roy Andersson there.” That was enough to flag Vasyanovich’s name as developing talent, and fourth time out turned out to be the exact right moment to check in.

Ukraine, 2025, after a (presumably/plausibly) forthcoming war: following a fellow ex-soldier’s suicide and the subsequent closing of the steel factory they worked at, Serhiy (Andrii Rymaruk) takes a job driving potable water to war zones while getting involved with a volunteer group digging up corpses from the Donbass-et-al. areas in a first attempt to understand recent history as literal autopsy. Atlantis has 28 shots (yes, I counted) in 108 minutes, and Vasyanovich immediately establishes both technical acumen and an idiosyncracy that makes his voice meaningfully distinct from the sum of his inspirations. The first shot is an overhead heat-vision camera view that eventually clarifies itself as a corpse’s burial. This specific color palette eliminates easily perceptible depth, so it’s unclear at the get-go what’s happening—the hole where the body’s being dumped doesn’t initially pop out as beneath the land around it—until the topography is established. Shot two starts with a snow-covered but otherwise blank expanse of field, then populates the frame, left to right, with eight black human targets planted one by one for shooting practice, filling out and recharging the composition. Vasyanovich is a giganticist who achieves spectacular effects: shot eight has molten steel pouring, orange and magma-like, down a hillside slope, a spectacular/dangerous display of color on a large scale. Elsewhere, large tractors are picked up by even larger ones, or mines deliberately exploded by soldiers unexpectedly shoot rocks and other debris into the foreground from above, a fun and unexpected surprise.

There are arguably two centerpiece shots: one (number nine) has the steel factory’s closure announced by a massive talking head—some British executive or other projected onto a large screen, declaiming the usual shutdown nonsense about how “new times are upon us” and how “new technologies” (i.e. layoffs) provide “new opportunities (TBD, never), like a really thick corporate parody of Wizard of Oz. “Let’s drink,” his speech concludes, and the composition changes—the screen on which the executive’s head is displayed, centered amidst intricate shadow-cross hatching of the lights pouring through the factory’s many floors, becomes the background as workers make their way to the bar, with a fight eventually breaking out. The focus shift from foreground to background is achieved by the manipulation of extras in choreographed motion, and it’s impressive. Another shot—simpler to execute, no less effective for that—has Serhiy stopping to pour himself a bath in the middle of nowhere, dragging a hose from his truck (frame back and left) to an empty orange tub front and center, heating up the firewood beneath before getting in—extended landscape art inscribed by one human performer, a funny procedural that provoked the most walkouts at once. These kinds of films may no longer be surprising, but they can still alienate mainstream viewers. When they’re rote, that makes sense; it was nice to see an unrepentantly arty, tableau-based fest film that reminded me why the sub-genre was important in the first place. Alas, shots 26 through 28 are misguided, a thematically literal-minded way to juxtapose the death and despair of its first 25 shots with Living Bodies In Motion. I’m inclined not to dilate on this last-minute shift, which is blunt and regrettable but doesn’t retrospectively recode what’s come before as just stupid.

Lijo Jose Pellissery’s Jallikattu proceeds from the novel but sound premise that all you need to make a movie is a bull running amok, a gimbal to follow its path of destruction, and dozens of extras to run from said bull in flabbergastingly long and elaborate shots. There are three or four such sequences, in which the camera races in and out of crowds—I presume that the bull is extensively animated, but the seams didn’t show, and it’s all very exciting. A bluntly characterized morality play in which the bull’s path of violence serves to expose and stoke Indian villagers’ long-simmering resentments, Jallikattu pauses in its dialogue scenes but stays lively, in part thanks to an extremely loud score from Prashant Pillai full of chanting and drums. It’s either energizing or numbing depending on your taste—for me, it was a real boost at the festival’s midway point.

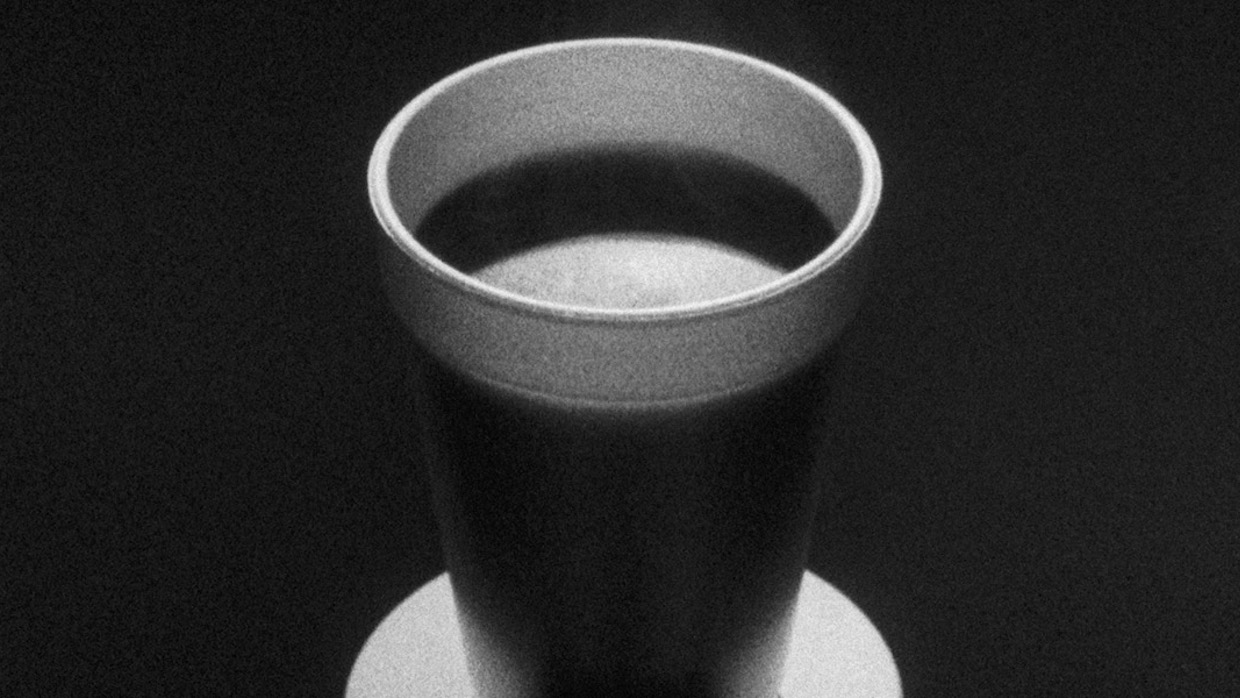

To return to and conclude with, unavoidably, money: the final film in this year’s suite of four Wavelengths programs is the latest salvo from James N. Kienitz Wilkins, whose work, I think, has only increased in the divisiveness of its reception since I saw Indefinite Pitch here three years ago—his increasing throughline is a comic voice that worries whatever his current anxieties are into easily legible form. Revisiting Indefinite Pitch‘s monologue structure, This Action Lies begins by Wilkins saying he’s here to deliver an apology, self-consciously leaning into the mixed reactions his work generates, but he doesn’t actually end up apologizing for anything. Instead, Wilkins travels down a very modern k-hole (quick, name all of Dunkin’ Donuts’ slogans since 2001!) over black-and-white images of hot coffee, making a series of unlikely associative leaps that transmute crap advertising ephemera into an unlikely path towards contemplating financial sustainability as a marginalized filmmaker, parenthood and death.

While accepting Godard’s invitation to see the universe in a coffee cup, Wilkins returns to his preoccupation with medium specificity, pointing out that the footage we’re seeing is 16mm that was then transferred to 35mm before being finished digitally. It does have a nicely filmic look, albeit one inevitably/conspicuously digitally mediated (blacks and digital still are not a great match)—all that being the case, he asks, are you impressed? Are you more impressed because it’s more expensive? The new elements here include Wilkins’s new child (who makes a crying audio cameo mid-voiceover recording) and a seemingly sincere emotional fragility about adjusting to a new stage in life that’s actually quite moving. Wilkins’s work may be too specific in its concerns and reference points to ever reach an audience wider than those who can keep up with the inside baseball, but it’s been a great recurring highlight of the last few years of viewing. I’m glad he’s here to refract every single worry I have during festival season(s) into something much funnier and richer, fretting through the film-related concerns of the day but not getting lost there, finding a path back to the real world in the end.