Back to selection

Back to selection

Wavelengths 2019, Program 4: Full Circle

Billy

Billy The fourth, and final, of this year’s Wavelengths shorts programs returned to the curatorial logic of the opening night, bringing together half a dozen disparate sensibilities based on formal, rather than thematic, common ground—in this case, their shared interest in performance. With one exception, the coherence here was more immediate than in the first slate’s buried interest in image production, though the styles of performance deployed across these works bear little resemblance to one another.

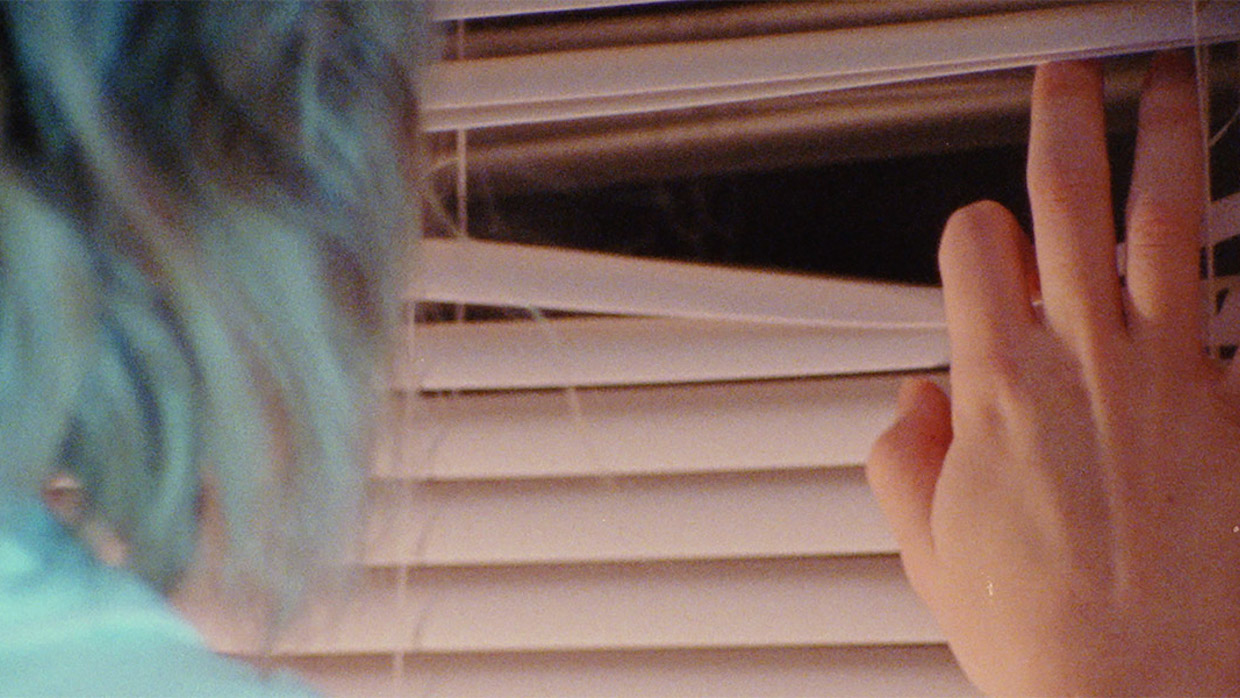

The program began with Zachary Epcar’s Billy, a quick, cool sip of Michael Robinson-aid recounting the domestic unease experienced by its eponymous male lead (Peter Christian), a loutish 30-something wracked by nightmares of falling, and his girl Friday, the icy blonde Allison (Kym McDaniel), whose only consolation when he wakes screaming is to remind him that “they say if you hit the ground in your dream, you really die.” Their anxious performances, landing in the sweet spot between soap and student production, reverberate out through a structure of found footage of suburban nocturnes, by turns haunted and lightly surreal. The noisy thinness of this low-grade digital sits with appropriate unease next to the rich reds, whites, and blues of Epcar’s clean and muted 16mm photography, which in emanating the sense of a past worth no one’s nostalgia, is perfectly modern. I recently wrote at length about Epcar’s four major films to date, so I will keep the present report brief and conclude by noting that Billy, though less surprising in its overall shape than the best of his previous work, effects an intriguing rebalance of the suburban elements he’s torqued into strange forms over the last five years. In moving from an oblique to a perpendicular relationship to his material, he’s produced a comic portrait of the bland paranoia and emptiness of life inside the late-American McMansion worthy, in the cruel accuracy of its caricature, of John Currin.

A different kind of domestic drama drives Edward Owens’ Remembrance: A Portrait Study, the single best film in this year’s selection. Having recently reentered circulation following five decades in obscurity, Owens’ brief body of work—it comprises only four films, made under the tutelage of Gregory Markopoulos in 1966 and 1967, before he had turned 20—offers a reconciliation of baroque montage and diaristic content as exquisite as any achieved by Markopoulos’ other great student, Robert Beavers. Shown here in its sound version, which plays both Marilyn Monroe’s performance of “Runnin’ Wild” from Some Like It Hot and Dusty Springfield’s “I’m All Cried Out” in their entirety, Remembrance is, as J. Hoberman called it, Owens’ “coming out” film: he announces its title on the soundtrack not as Remembrance: A Portrait Study, but as No More Tomorrows, offering a direct rejoinder to his previous film, the straight, white psychodrama, Tomorrow’s Promise. The film’s first half presents portraits of three women—one seated alone in a wicker chair, the others seated behind a beer-filled bar counter—in pulsing in-camera montage which moves with more rhythmic freedom than any of Markopoulos’ work I know, at times layering three or four exposures atop one another, at others dropping into sparse sequences built largely of black frames, into which images burst, before receding as quickly. After roughly two minutes, as Monroe’s song comes to its conclusion on the soundtrack, Owens lands on an image of a small brass putti, or perhaps it is Cupid, holding aloft a brilliant red flower or ribbon. He holds on this image for ten seconds—a length which, given the pace of the montage to this point, feels several times as long—before dissolving to an image of his mother, Mildred Owens, seated in the same wicker chair we had seen before, as she gazes off into the distance with a mood of self-absorption that can only be called regal. As she lifts her cigarette and takes a drag, the soundtrack shifts to the Springfield track, and Owens slows his montage, moving over the course of a minute through three further shots of his mother with no flicker or multiple exposures, as he pushes the 16mm to the edge of its ability to render Black skin. Eventually the film resumes its prior rhythms, layering images of his mother which are by turns tender (as she reaches toward the camera) and terrifying (though there is no direct audio, we see her let out what must have been a thunderous scream). Owens inserts himself into this sequence via a still photograph, his head in his hands, bashful and alluring. As I will be writing at length in the future on the whole of Owens’ work, I will leave off further consideration for the time being, and simply conclude with a plea that any teacher or programmer who might be reading this please do whatever is necessary to ensure that their students and audiences can see this film.

The exception I alluded to above arrived next, Deborah Stratman’s Vever (for Barbara). Having been approached in the space of a month last year by both Barbara Hammer, who passed away this March, and the Walker Arts Center with commissions—the former an informal request to finish a film out of footage Hammer had shot in 1975, the latter a formal invitation to take part in a program which funds the creation of work based on the institution’s collection—Stratman combined the two, bringing in Maya Deren’s field recordings and written reflections from her time in Haiti to satisfy the Walker’s requirements. This was not, or not only, a matter of professionally expedient feminist genealogy: Hammer’s footage was the product of her own journey to the global South, a 1975 motorcycle trek from the Bay Area to Guatemala—a trip which also produced Hammer’s iconic On the Road, Big Sur, California, a photographic self portrait showing her seated side-saddle atop her BMW, one leg impatiently cocked on the gas, the resignation in her eyes overcome by the resolution of her jawline. “I didn’t have any intention when I took off,” Hammer tells Stratman in the phone conversation which forms one half of the film’s soundtrack, “I was kind of sick of relationships in the Bay Area. Especially one, where the woman had like three lovers. I don’t know, maybe I was the fourth, and it really felt like a bummer.”

Though she managed across her five-decade career to bend all manner of genres, from the pastoral to sci-fi and well beyond, to fit her needs, the proto-Eat, Pray, Love narrative which led Hammer to Guatemala was apparently too much for even her to overcome: “I couldn’t find any political content, actually,” Hammer, whose integrity was absolute, rasps on the soundtrack. “Or personal context for the film. So I didn’t see a reason to print it. I didn’t have much money.” And so it sat for four decades. It’s easy enough to see what she meant. Her footage, handsomely shot on color 16mm stock, is for the most part indistinguishable in its curiosity from any anonymous ethnographic study. As Hammer takes in the bustling activity of what appears to be a town’s main square and marketplace, the megawatt force of her personality registers chiefly in her ability to capture the attention of her subjects, charming them into brief portraits as they go about their daily commerce. Stratman, as intelligent an editor as any working today, has deftly arranged this footage, weaving—the film opens on an image of just this activity—Hammer’s images into pleasingly subtle patterns.

Having established Hammer’s presence in the film’s third shot, her hand entering from behind the camera to accept a bowl of horchata, Stratman proceeds through seven brief portraits of girls and young women, all of them returning the camera’s gaze. She then pulls back to define the broader social field we’re seeing, with a sequence of five shots unified by the presence of baskets—four of them carried atop the heads of women—sketching the means of circulation of the market’s goods. The images continue on like this, as rhymes and associations bubble, but are never forced. Occasionally, Stratman introduces footage Hammer captured away from the marketplace, largely showing the local flora, a range of lovely cacti and palms. One particularly striking sequence, set to the only instance of Deren’s audio recordings I’ve been able to discern after a number of viewings, soundtracks Hammer’s handheld footage, as she exits the jungle into a clearing offering an expansive view of the landscape, with the sound of Vodou drumming, the percussion so irresistible that it sets the image itself shaking. (I suspect Hammer originally shot this footage at a low frame rate, though it’s impossible for me to rule out that this was Stratman’s own intervention.)

For the most part, the soundtrack moves between Hammer and Stratman’s phone conversation and Teiji Ito’s score for Meshes of the Afternoon—another retrospective act of “completion”—while Hammer’s images are occasionally overlaid or broken up by quotations and vever (glyphic drawings used in Vodou ritual) taken from Deren’s Divine Horsemen. Deren’s texts offer an optimistic echo of Hammer’s own concerns: “That I was defeated in my original intention assures that what I have recorded reflects not my own integrity but that that of the reality that mastered it.” And yet, the unfortunate fact that Deren’s own abandoned footage from her time in Haiti was finished by Ito more than two decades on from her death into a film not worthy of her name creeps into Vever through these quotations, opening up, to my mind, a certain numbers of doubts. “So I thought, ‘Oh, let’s go back. Let’s record some sound. Let’s hear people talk about how the market has changed. How, perhaps, they don’t weave anymore. Let’s see how Western markets have taken over indigenous markets, and in doing so, changed the culture.’” It’s unclear when Hammer thought this, but in any event, this return is not part of the work which was finally fashioned out of her trip. From a film full of voices, those absent linger longest.

After the retrospection of Vever, the program turned toward the future with Annie MacDonnell’s Book of Hours, which, in its low-key way, pushes both domestic space and its typical activities toward the cosmic. MacDonnell opens on an unassuming composition, in the film’s consistently flat 16mm, of a modestly sized living room—its walls white, its fireplace non-functioning, its floor wooden—which is filled with a couch, a single cushioned chair, and a rather worn low table set atop an Afghan rug, barely glimpsed. She allows us enough time to fully take in this space before a cut tilts the camera 90 degrees to the overhead angle of tabletop animation, the downward view taking in a wooden surface—it may be one of the two present in the opening image—onto which a young child’s hand sets a placemat-size image of blue and white dots against a black background, the cosmos as one finds it occasionally on the subway floor. The prosaic swerves into the strange when, having positioned the picture just so, leaving a right angle of wood visible along its left and lower edges, the child begins an obviously artificial gesture. They draw their fingers together to a point, turn their hand, and, then slowly open them again while reaching toward the camera’s lens—“ich fasse den plastichen Tag,” wrote Rilke at the start of his Book of Hours, “I grasp the malleable day.”

The child’s gesture sets Book of Hours moving. For the next minute, the frame holds on the same overhead view, as hands, some of them now adult, continue to place and arrange printed images atop this wooden surface: illustrations of snowflakes, a postcard of stained glass, op art, Byzantine decoration, new age kitsch. A second child’s hand—younger, a toddler—repeats the earlier gesture, reaching toward the lens, though with much less intention. The final image of this sequence enters the frame wrong side up, betraying itself as a calendar. An abrupt edit returns us to the initial living room, now seen from a different angle, as a child’s ball is kicked into the frame. On the soundtrack, MacDonnell balances the calendar’s time with a listing of spaces modeled on the initial inventory in Perec’s Species of Spaces. “Space. Air space. Interior space. Space odyssey. Space alien. Available space.” As she whispers, giving the sense that this recording is perhaps being made during nap time, the camera wanders over the living room, taking it in as the children play. After roughly a minute, the image lands suddenly lands in the work of another Rainer, Lives of Performers—a film full of piled and arranged still images, though we see only its dance sequences—which is quickly revealed to be playing on the screen of a MacBook: “Cyber space. Abstract Space. Virtual Space.” She stays with Rainer’s film through the conclusion of her catalogue. “Space exploration. Common space. Null space. Intimate space. Personal space.”

For the next two minutes, MacDonnell works through her own variations on the intricate entanglements of public and private so critical to Yvonne Rainer’s work. In a series of shots, mainly from the same overhead angle as before, we see both children engaged in mundane gestures, at times with considerable volition—the first “number” shows the older child tugging forcefully at the hands of a grown man—and at others not so much directed as shaped, their bodies literally placed into position. The tension and tenderness of these parental dances finds its release when the implication of table-top animation of the overhead angle is finally embraced: the child sets down an image of the galaxy and, with the rush of an airplane on the soundtrack, the film launches into a flicker sequence built of short-frame bursts of what have already been shown, supplemented with pictures of a similar sort. It’s to MacDonnell’s considerable credit that this passage escapes the long shadows of both Sharits and Mack; her addition to the forms these two have mastered is the inclusion of brief (I believe single-, rather short-frame) instances of the domestic space itself, sudden intrusions of the camera’s everyday illusionism which set the flickering flat images floating in an uncanny volume, “the space between two notes.”

The hurtling motion of this cosmic passage, which more than earns MacDonnell the allusion to Sun Ra offered in her inventory, crashes back into Velda Setterfield’s showstopper from Lives of Performers, a dance of baffling elegance. MacDonnell again stays with Rainer’s images for almost a full minute, the sense of her own captivation rhymed by the child seen pawing at the screen, before she transitions to her film’s final movement. The medium is now an iPhone rather than a MacBook, the frame matched to its height, leaving ample space on either side. As the phone plays images from the final dance between James Barth and Epp Kotkas from a second Rainer work, Film about a Woman Who…—a dance which, in its use of an inflated ball, brings MacDonnell’s film nearly full circle—the background jumps between three illustrations of spaces built for the divine. In a year full of films concerned with the problem of belief, Book of Hours, through its heady and precise play of scales, is among the few to offer any form of wisdom.

An equally active, though to my mind much less successful, play of scale and distance shapes John Torres’ We Still Have to Close Our Eyes. Derived from the model of Pere Portabella’s Cuadecuc, vampire—the result of Portabella shooting in parallel with the production of Jess Franco’s Count Dracula, carving out his own orthochromatic telling of the same tale—Torres’ film is a bit of techno-fiction built of material shot on the sets of recent works by his fellow Filipino filmmakers, Lav Diaz and Erik Matti. Given that I am several years behind on Diaz’s overwhelming output, and that I know Matti’s work not at all, it may be that significant intertextual activity is occurring at levels unavailable to me, but based off what I do know of Diaz’s films, it seems that the relationship between the two levels of production here is chiefly one of convenience. In any event, the film, like Second Generation the night before, offloads nearly all of its narrative scaffolding onto onscreen titles. Where Charles’ language left a certain amount of space for her sounds and images to fill, the prosaic text in We Still Have to Close Our Eyes risks obviating the need for sounds and images entirely.

And indeed, the full first minute of the film’s thirteen is given over to text, thin white on a black background, laying out the b-movie scenario, which involves an app allowing its users to remotely drive real motorcycles with real riders and a shadowy figure, as expected, putting this app to unintended ends. After two minutes of establishing shots—the moon through clouds, a figure seen from behind while seated in a car—which establish very little, we learn that one of these avatar-riders has lured a handful of cops to a karaoke joint, where they were promptly blown up. This information is delivered in text atop the image of a group of men standing around what appears to be a disemboweled frog, though this inscrutable scene is itself quickly clarified by an onscreen caption—“RECOVERY OF A MECHANICAL FROG BY INVESTIGATORS IN LAGUNA”—implying that this strange little object was a homemade explosive. A suspect is quickly collared (within the very same passage of annotation as the clarification of the frog), and his defense articulates the film’s pulp philosophy, “I am just a driving app. I only have my body.” The ensuing investigation, which makes up the bulk of the film, plays out even more obliquely than the crime. We largely see people standing around, waiting (as one so often does on a film set), hammered by a caption into, for example, an image of “children willingly playing as avatars.” A long sequence inside a jail hints in the direction of broader conspiracy. And then the text disappears entirely, leaving the final few minutes, in which the cops don tactical gear while conducting a raid and a young man is seen lying dead beside his wrecked motorcycle as a woman stands above him and impassively snaps a photograph of something off-screen, to play out in the absence of overt narrative direction. Does it matter that we don’t know where this military-grade raid is occurring? Or that we don’t know the identity of this dead rider, or why a woman, apparently unconcerned by his death, is taking photos? Given the present political situation in the Philippines, and Duterte’s thuggish and militarized police force in particular, the narrative here, sketchy as it is, carries a considerable charge. And the history of art under, and against, fascism is full of work which leaves what is most critical unsaid. The trouble with Torres’ film is that I can find no route into what isn’t being said, leaving it equally unsatisfying as both pulp and commentary.

The evening’s final film, James N. Kienitz Wilkins’ This Action Lies, closed the circle of inquiry opened by Austrian Pavilion, bringing this year’s program from the physical form of gatekeeping to the anxiety of at least one artist who has managed to make it through to those rarefied spaces. Two films provide a pleasing formal balance as well, as This Action Lies softens the severe structuralism of Fleischmann’s film, a match for even the most hardcore products of the London Filmmaker’s Co-op, into something nearer to the incidental rigor of the early Warhol films. I say “nearer to” advisedly, because the montage of Wilkins’ film slowly emerges as its dominant formal quality—which would fittingly make Sleep the most reasonable point of comparison. The set-up is simple enough: a cup of coffee, placed atop a somewhat small pedestal, is filmed in close-up, the only visual variation being the change in the placement of the scene’s lighting, which moves from its initial position behind the cup to subsequent angles from its right and left, a decomposition, as Wilkins has confirmed in this essential interview with Mary Helena Clark, of the conventional three-point setup. Wilkins, ostensibly, shot a single 1000’ reel of 16mm film of each of these set-ups, rendering the final product, with its perfectly efficient 1:1 shooting ratio, thirty minutes long. The lighting, in addition to providing visual variety (another very non-Warholian concern), directs the monologue which Wilkins delivers, with the exception of a two-minute interlude, in unbroken speech across the film. Each set-up is attached to a pronoun: the backlit scenes are spoken as “I,” those lit from the right speak to and of “you,” and those lit from the left concern “he.”

Wilkins begins this monologue, which plays out through heavy reverb that leaves his words to hang, interfering with what follows them, by stating his intentions: “I’m making an apology. Yes, I’m making an apology. This is an apology.” He is, he says, apologizing for the offense he has caused through either “his lack of action” or “his lack of commitment to a tradition.” Within 45 seconds, he announces that he’s getting ahead of himself and swerves, announcing that he’s “been hearing voices lately,” and with that, leaving apology behind. From here the film proceeds through variations on what’s become his trademark: ruthlessly punning digressions on personal and social history, moving more or less at the pace of a Google search.

If it’s true that Wilkins’ work draws enough ire to require, if not an apology, then at least a justification—and it probably is, though little of this complaint has found its way into formal venues of criticism, so far as I can find—I suspect that the issue is not with either his lack of action or his lack of tradition, but rather with a skepticism (his word) regarding the potential of art today to do the things it has traditionally be taken to do. Whether one cares for the term “autofiction,” or dismisses it as just more branding, Wilkins’ concerns are those of the writers who’ve been stuck with it. Perhaps you too can hear Wilkins’ distinctive voice, a bass at once musical and nervous, speaking these words from Leaving the Atocha Station: “I had long worried that I was incapable of having a profound experience of art and I had trouble believing that anyone had, at least anyone I knew.” Like Lerner, Wilkins’ project, perhaps idiotic in its ambition, is an attempt to gain some satisfaction on this matter, to determine whether this is, after all, still possible—whether art might move someone to tears, and whether those tears would be genuine, and what “genuine” might possibly mean in such a context, and so on: “There, he’d said it, ‘faith.’ He’d come back to it. Despite the perceived accusations, here he was, arguing for faith.”

One’s response to Wilkins’ work hinges, I suspect, on whether or not one finds him to be working in bad faith, an accusation he takes considerable pleasure in toying with. Though This Action Lies abounds in instances of apparent frankness—regarding the economics of independent filmmaking, or the experience of being a father—each is undercut by Wilkins. A moving passage in which he reflects on the fact that his daughter will be here after he is gone (which is moving not for its overt sentimentality, but for its expression of the fact that there is nothing more horrifying to a parent than the notion that the opposite might be true), is preceded by Wilkins “sensing a contradiction” in his line of thinking regarding taste and tradition and swerving, “bringing his daughter back into the discussion, probably to tug at the audience’s heartstrings and afford him some sympathy.” Perhaps this is finally nothing but cynicism, the house style of the most sophisticated art being made in New York today. But here it’s worth noting that, through its montage, the rear-lit “I” exhausts itself early, just past the film’s halfway point, leaving Wilkins to reflect at a distance on the odd, inevitable process of constructing a self, a process made odder still when that self is offered for public consumption. Wilkins, of course, accounts for the complications of this lyric reflection, the tradition which he is intent on bringing into the present, just as he accounts for everything else one might think while watching his film: “Yes, it seems if you stare at something long enough, the best you can hope for is to see yourself.”