Back to selection

Back to selection

Shutter Angles

Conversations with DPs, directors and below-the-line crew by Matt Mulcahey

Shadowplay: The Artistic Benefits and Technical Challenges of Ozark‘s HDR Workflow

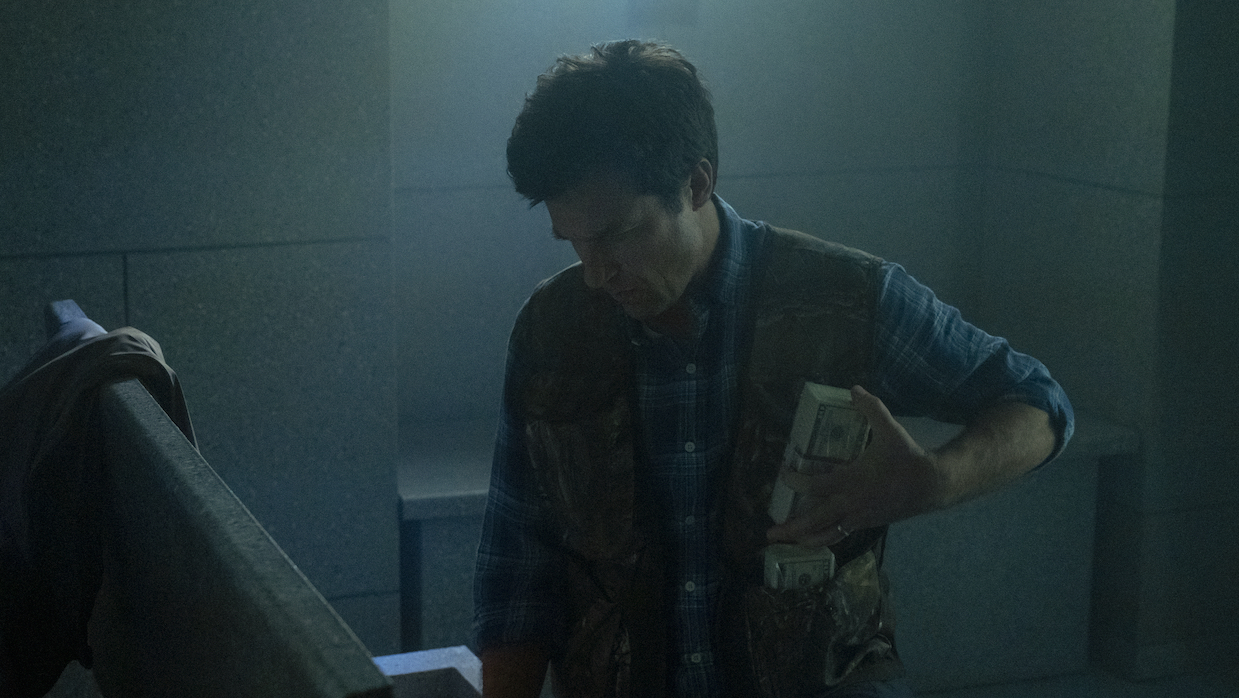

Jason Bateman in Ozark (Photo courtesy of Steve Dietl/Netflix)

Jason Bateman in Ozark (Photo courtesy of Steve Dietl/Netflix) Ozark is a “dark” show in every meaning of the word. The story of a criminal Missouri clan laundering Mexican cartel money through their riverboat casino is literally, metaphorically and photographically bleak. “Ozark is about what happens in the shadows of our society, in the underbelly, and the fear and anxiety that permeates that environment,” said cinematographer Armando Salas, ASC. “Everyone can relate to that feeling on some level—the feeling in the pit of your stomach that comes with knowing you’re doing something wrong. We try to embed that feeling in the look of the show.”

Sunlight rarely reaches the denizens of Ozark’s resort community. If financial advisor-turned-felon Marty Byrde (Jason Bateman) and his wife and partner-in-crime Wendy (Laura Linney) are discussing their latest scheme in a day exterior shot, there’s likely a 20’ x 20’ frame above them, shielding their moral turpitude from the cleansing rays of the sun. The look of the show—whose third season debuted on Netflix in March—is low contrast, low key and tinted in cool, pale shades of cyan.

In other words, Ozark’s most prominent aesthetic qualities are seemingly antithetical to the benefits offered by burgeoning high-dynamic range (HDR) display technology. Typically paired with 4K resolution and the ability to display wide color gamut, HDR-capable televisions boast a significant increase in contrast ratio from the standard dynamic range (SDR) sets most of us are currently viewing. HDR essentially allows displays to inch closer to showing us what digital cinema cameras have been capable of capturing for years.

The standard for SDR televisions is based on a peak brightness of 100 nits. Top-tier consumer HDR televisions currently offer in the range of 1,000 to 2,000 nits. High-end monitors used by digital intermediate colorists reach 4,000 nits. So, what in the world is a “nit?” In mathematical terms, “nit” is shorthand for candela per square meter (cd/m2). In terms of nomenclature, “nit” comes from the Latin word “nitere,” meaning “to shine.” And in useful parlance, a “nit” measures the brightness of your television, computer or handheld device screen.

Though HDR’s popularity is growing, many of us are currently viewing our content in the realm of SDR. So, why would Armando Salas and his fellow Ozark cinematographers Ben Kutchins and Manuel Billeter create an HDR-centric on-set workflow for the show’s third season? The answer is simple—delivery format.

Netflix requires picture mastering for its original content in Dolby Vision HDR color, a proprietary format in competition with the open-source HDR10 (think Beta vs. VHS). All other deliverables—including the SDR version many of us will see—are derived from that Dolby Vision master and its P3 color space and perceptual quantizer transfer curve, which replaces traditional gamma curves. SDR monitors live in a Rec.709 color space, meaning that even if a cinematographer chooses to make decisions during production based on their SDR monitors, that on-set image will not directly correlate to what viewers ultimately see.

“One of the things that people get confused by is that they think, ’Well, if 90 percent of the people are going to be watching the SDR, then I’ll just view SDR on set, and I can stay in my comfortable paradigm that I’ve been working in for a long time. We’ll just make the HDR coloring look similar to the SDR,’” said Salas. “But, that’s actually not the case. In Dolby Vision and most of the true HDR workflows, your camera negative is mapped into HDR color space first, and from there the SDR is derived. That SDR version has nothing to do with what you see on set if you’re dealing with a Rec.709 LUT.”

Salas learned that lesson on Ozark’s second season, when the decision to release the new installment in HDR came just before principal photography. When he was offered another Netflix show shortly thereafter—the sci-fi drama Raising Dion—Salas made the leap to an on-set HDR workflow that prioritized making decisions based around the Dolby Vision deliverable. “We wanted to use the technology to its fullest capabilities instead of playing triage in postproduction,” said Salas. “It ended up being a seamless integration. It didn’t slow anything down. It barely affected the cost. Really, it was just the cost of having better monitors on set.”

When setting up the initial workflow on Raising Dion, Salas reached out to fellow DPs for guidance and found few of them adopting the practice. “I called other cinematographers who I knew were delivering in Dolby Vision for Netflix, and I don’t think I talked to a single one [who] had an HDR workflow [on set] except for Erik Messerschmidt on Mindhunter,” said Salas. “It’s slowly changing, but even now most shows are not implementing an HDR workflow.”

After the positive experience on Raising Dion, Salas and his fellow Ozark cinematographers took the HDR plunge for the show’s latest season—the process went “incredibly smoothly,” he said. “There were some tech hurdles, but I would say no more so than on an SDR shoot,” Salas said. “Making adjustments and tweaks on set in our delivery color space was a huge advantage for everyone involved, and I got much closer to where I wanted to be in final color.”

Moving to an HDR workflow wasn’t the only alteration for Ozark’s latest chapter. For Ozark’s first two seasons, the widest aspect ratio Netflix was comfortable with was 2:1. However, the second season of Mindhunter, released in August 2019, was permitted to push that ratio to 2.2:1, and Ozark followed suit. To further the show’s desire for, as Salas put it, “a bigger canvas,” Ozark also switched from the Panasonic VariCam’s Super 35mm sensor to the large-format Sony VENICE. The increase in format size and resolution (up from 4K to 5.7K), coupled with HDR’s increased contrast, meant Salas and his co-cinematographers had an even tougher battle on their hands against the bane of contemporary DPs—digital sharpness. “There was a huge increase in apparent sharpness, and the way we combatted that was by using vintage glass that we could go to for specific effects, whether for portraiture or for a wide shot where we really wanted to focus the eye on a certain part of the frame and have massive falloff in terms of depth of field,” said Salas.

Shifting away from the Cooke S4s used on the first two seasons, Ozark turned to vintage rehoused Leica Rs. Leica Summicron-C lenses were also part of the package, as was a Leica Noctilux-M 50mm rehoused by TLS (True Lens Services). The Noctilux opens to a T0.95, one of many challenges faced by first assistant camera Liam Sinnott, who was certainly accustomed to tough focus pulls after the razor-thin depth of field on the diopter-happy HBO show The Outsider. “My job as a focus puller didn’t change all that much because of the HDR workflow. I still pulled off an SDR signal on a 13-inch monitor, but we did shoot at a shallower stop this season, so my job did get harder,” said Sinnott. “But it’s good to be challenged. It keeps you fully engaged.”

To further ward off the specter of digital sharpness, Livegrain—a proprietary process that mimics the unpredictable dance of film grain—was added in post. “Having enough sharpness and detail without it feeling overly sharp and electronic is a constant battle,” said Salas. “The combination of vintage Leica glass and Livegrain gave us the creamy skin tones we were after, with a filmic texture.”

On set, Atlanta-based digital imaging technician Joe Elrom spent the show’s first two months setting up the new HDR workflow. That workflow began with an S-Log3 signal from the Sony VENICE to Elrom’s cart, where he added CDL looks using Pomfort’s Livegrade on Flanders Scientific DM250 OLED SDR monitors. Elrom then sent the graded signal downstream to the video assist cart, which routed it to two different villages—one set up for SDR for various crew members, another with an AJA FS-HDR converter, so that the episode’s director and DP could toggle back and forth between HDR and SDR viewing.

The HDR station was equipped with a pair of Canon DP-V2411 LCD monitors, which won out during preproduction tests over the Sony BVM-HX310 partly because their 24” size was more accommodating than the Sony’s 31” screen. The Canon monitors maxed out at 600 nits, which Salas found to be more than enough brightness for Ozark. “If I’m shooting an intimate scene on Ozark where two people are sitting in a dimly lit living room, we might not have anything above 100 nits even in the HDR master. In fact, you’ll never see anything in the show above 600 nits on any display,” said Salas. “Just because you have all this room at the top end of the curve doesn’t mean you use it. The way you expose the negative is still part of your craft as a cinematographer.”

In HDR, managing highlights is a crucial part of that craft. A practical lamp that seems innocuous in SDR can be blisteringly bright and pull attention from the performances in HDR. “A lot of times, it’s counterintuitive because you have so much more room on the shoulder of the curve in the highlights, yet you actually end up playing things like practicals dimmer,” said Salas. “Having the ability to dial back on highlights when it feels like it’s too much is important, and monitoring that in HDR allows us to make those decisions on set instead of dealing with tons of masks and power windows and secondaries in final color.”

Working in HDR also allowed Salas to bring out detail in the murky depths of Ozark’s shadows. “If you’re dealing with something that’s really low-level lighting—like Marty in a dark room with just a bit of a door that’s open, letting some light in—you have all this expanded information in the toe of the curve to really fine tune the decision-making of how much separation there is in those shadows between black and grey, and how much of an eye light you add just to feel that performance while keeping him essentially in the dark,” said Salas.

Making those decisions on set rather than in post made life simpler for Company 3 colorist Tim Stipan, who has worked on all 30 episodes of Ozark. “An HDR grade is so much easier when the DP has set the light values in HDR [during the shoot]. I don’t have to work the digital negative as hard,” Stipan said. “Monitoring in HDR while shooting is a luxury, and a lot of productions aren’t doing it, but they end up spending more time in color correction trying to mitigate issues of blown-out highlights. Those color correction hours versus having a HDR monitor on set is something to be considered. Ultimately, the images will look better if the DP, DIT and gaffer can work together to create the best HDR version, then dumb down from that for the SDR version.”

That “dumbed down” version is created by Dolby’s Content Mapping Unit (CMU), which analyzes the HDR footage and creates an SDR trim pass based on Stipan’s preset parameters. Working in DaVinci Resolve, Stipan graded the HDR version and made adjustments to the SDR trim pass while monitoring each on Sony BVM-X300 displays. He also checked his high-end monitors against a consumer Panasonic OLED HDR screen placed above his workstation. “That setup allowed me to monitor two different flavors of HDR, one on a professional monitor and one on a consumer monitor,” said Stipan. “That way, I can see the differences and make any necessary adjustments to ensure they are as close-looking as possible.” As he worked, Stipan also tweaked the CMU’s automated SDR pass as needed. “There might be a bright scene or a dark scene where I’ll make an adjustment to the trim for that particular scene, but it’s usually the same adjustment for the entire scene,” said Stipan. “It’s very rare that I would ever need to do a shot by shot adjustment for the SDR.”

Because so much of Ozark exists in the shadows, the low end of the curve might be very similar for the HDR and SDR versions. Salas offered the example of a scene with three actors in low light levels with practicals in frame. “The scopes for both the HDR and SDR might match 90 percent in that scenario. Most of the information might be below 50 nits in the HDR or 50 IRE on the SDR version,” said Salas. “The way those practicals are mapped is where it’s different. On SDR, they might come up to 70 IRE, but on HDR they might be going to 250 nits. But for me, where the technology really shines is that consumers now have 10-bit displays at home that are able to render tonal curves accurately without banding artifacts.”

Salas emphasized that HDR is just another tool—but a tool that cinematographers working in the format must embrace and work to master. “Having an understanding of how to use it is really important because, as cinematographers, if we don’t take charge and take ownership of the technology, somebody else will,” said Salas. “We spend so much time and care on set as the author of the image, and to not be able to realize that intent in post would be a shame.”