Back to selection

Back to selection

“We Could Have Made A True Crime Film, But Decided Not To”: Jiayan “Jenny” Shi on Finding Yingying

Finding Yingying

Finding Yingying Yingying Zhang came to the US in April 2017 to conduct a year of research on photosynthesis and crop productivity at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. She was considering a doctoral program at the university and planned to marry her boyfriend, Xiaolin Hu, later that year. In her diary, she wrote, “Life is too short to be ordinary” and was anxious to fulfill as many ambitions as she could—but disappeared June that year. It was later confirmed her life had been taken.

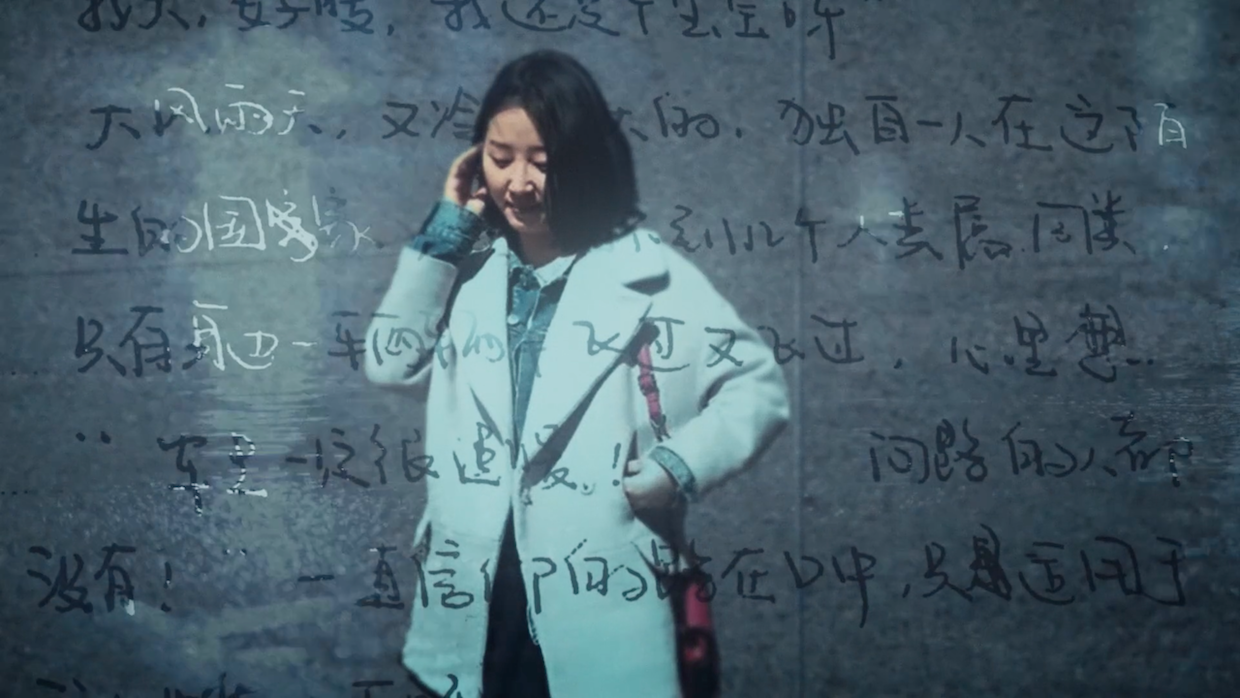

Jiayan “Jenny” Shi, the director of Finding Yingying, accompanies Yingying’s parents, Ronggao Zhang and Lifeng Ye, her brother Zhengyang and her boyfriend through the initial search efforts, ensuing prosecution and aftermath. Unlike most documentaries that navigate a “true crime,” Shi stayed close to the family and friends of the victim, only expanding her scope when she felt it was important to Yingying’s story. Shi sees much of herself in Yingying: she relates to her diary entries about feeling alienated in the US, they graduated Peking University in the same year, and the two even look alike—as Yingying’s mother tells Shi on camera. Naturally, Shi becomes an integral presence in the film, finding herself an effective and appropriate intermediate for Yingying’s story, and realizing that she is too immersed to remain a detached fly on the wall. Shi even does the voiceover narration of Yingying’s diary entries, so the usual dividing lines between filmmaker, camera and subject are thin or nearly none. Those barriers can serve to protect the filmmaker, but Shi was in deep with little protection. She talked to us about her sensitive and intimate approach to humanizing Yingying, her family, and her friends, in the fallout of an abominable crime.

Filmmaker: True crime documentaries tend to keep a distance from the subjects of the investigation in question, so that they can more easily contradict them later when they’re picking through the puzzle. That approach has always made watching those films uncomfortable to me. But with your intimate approach to Yingying’s family in Finding Yingying, and how you steep yourself in the events of Yingying’s disappearance, I felt safer knowing you would not construct this to upend or contradict your subjects, chiefly Yingying’s parents and boyfriend. Do you think filmmakers documenting a “true crime” have any moral obligation to get close to the victims and investigation when they approach material that is this heinous?

Shi: I think it really depends. When I first approached the family in Finding Yingying it was more about volunteering, not about being a filmmaker who wanted to make a feature-length film with them. When I first heard Yingying went missing, I was a student at Northwestern University and heard the news of her disappearance through my colleague’s alumni group chat on WeChat. At that time, I was just like any other Chinese student, spreading the word of her disappearance to see if anyone could find her. Then I found out Yingying and I went to the same university back in China. Our similarities really stuck with me, and I followed the incident very closely. When Yingying’s family arrived in the US, I went down to Champaign to see what I could do. At that time, I was a journalism student, so it was very natural I was curious about what was going on and what would happen next.

I visited them through the volunteer groups—there were a lot of volunteers helping them. I would sometimes help them with translations. Then I met another volunteer, a senior student at U. of I., [Shilin Sun, the film’s coproducer and DP]. He was interested in filmmaking. We started to think about whether we should document what was going on or not, since there were already a lot of reporters. But this was a story that was very close to us, close to our own identity, so we decided that we should follow.

Three weeks later, the FBI arrested a suspect and didn’t believe Yingying was still alive. That was the moment the whole story went a different direction than anyone expected. We thought we would find her safely, or that she would just come back. But the whole situation was out of control, and we really witnessed how desperate and helpless Yingying’s family was. We had to think about what we could do with all this footage. I pitched the idea to Yingying’s family and her boyfriend about potentially documenting their journey in the US and the places Yingying used to study. So, that is how I started. I didn’t really go into this as an investigative journalist. It was more about volunteering and witnessing the story unfold, waiting to see what would happen. That’s how we built trust with Yingying’s parents and the boyfriend. In the first five months when the parents were in the US in 2017, 70 percent of the time we spent with them was without the camera. Yingying’s mother was actually happy to see me, to have me just sticking around, this girl who looked like her daughter. I wouldn’t say I brought comfort to her, but somehow she felt happy that someone was there. I was happy to do that.

Whenever we wanted to film, we would ask them first. “We’re going to film a quiet moment for ten minutes, is that okay?” That’s how we started filming and dealt with the ethical situation. When they were very emotional, I would ask myself if I should keep filming or not. So, I was asking them these questions all the time.

Filmmaker: You get so close to the Zhang family that the viewer can feel how much they start to lean on you in the film. Then, the investigation takes such a macabre turn. How do you protect yourself when you’re immersed in something so heavy and there are emotional obligations to the subject?

Shi: There are two ways I think about this. One is how the family felt about us filming them. It depends day to day: They may be okay shooting today but not tomorrow, even if both days are the same situation. I had to feel how the family felt on that day exactly. Sometimes I think Yingying’s family was too nice. They didn’t want to say no to the people who had come to support them. So, there were miscommunications between us. After we would finish days like that, they’d say, “Today was not a good day to film.” We would apologize to them and make sure that didn’t happen again.

We filmed them over the course of two years, but we never stopped asking them [if it was okay to film]. In 2017, 2018 and 2019, the situation kept changing. At first, they didn’t know where Yingying was, then they found out she was probably dead, then they found out that a heinous crime happened to her. Their feelings were all so different, so we were very careful about the access we had and how we maintained the relationship with them. I wouldn’t push too hard. Everything I learned at school was “fly on the wall,” so I thought people would forget the camera. But that wasn’t the case. [laughs] It’s always there. So we really thought about how the family felt.

The other way to think about this question is how I feel as a filmmaker. It’s my first feature film. I’ve never covered a search story, or a grieving family looking desperately for their daughter before. For me, it was really challenging, because I spent so much time with them. Sometimes I couldn’t bear those emotions, not only from the family but my own. I was often questioning my ethics, whether I was right or wrong on a specific day. On the other hand, thinking about what Yingying wants and also my own identity, my own parents. My parents were very worried about my safety when they heard the news that Yingying had disappeared. My parents were in China; you know how big the case was there. There were a lot of emotions I was dealing with while trying to remain effective as a filmmaker. That was really challenging for me.

I wasn’t alone when I dealt with my own emotions when filming with the family. During the trial, our producers Brent E. Huffman and Diane Quon would text Shilin and me who were sitting in the courtroom every day, and see if we were doing okay. I also got support from the whole Kartemquin team, including Gordon Quinn and Tim Horsburgh, who constantly gave me advice to navigate ethical dilemmas. “Finding Yingying” is made through a joint effort, and the experience I have gained in this journey has been significant.

Filmmaker: Did you work on the edit? If so, how do you navigate the emotional toll of working through footage like this?

Shi: We eventually hired an editor, John Farbrother. I had been editing until we found enough money to get an editor. It was very difficult for me to watch through the footage even though I was the one who captured it. Specifically, there’s the scene where Yingying’s mother starts crying and breaks down at a press conference when she arrives in the US. I used that scene for a three-minute demo, but it was very difficult for me to even edit that. I think it took me two weeks to basically contain myself and make sure my own emotions did not affect my own creative choices.

Filmmaker: Did you have to cut things out that were too intimate and compromised the family’s privacy?

Shi: It’s always good to talk about the power dynamic between the subject and the filmmaker. In this film I wanted to create that intimacy. That’s something that makes this film different from most true crime stories: we wanted to put the audience into the shoes of the family and really see the kind of hardships they’ve been through for the past three years. That’s what’s missing in the mainstream media. Whenever heinous crimes or tragedies like this happen, it’s important to see who’s forgotten behind the scenes. It’s important for me to capture this, but on the other hand it’s important for me to respect how much Yingying’s parents want me to show publicly—especially considering they don’t know English, they only know Chinese. Yingying’s mom cannot even read Chinese. I had power over them. So, when I was with Yingying’s parents I was very careful about the kind of questions I was asking and how much I was asking.

Early on I didn’t specifically ask about their feelings, I just kept the camera rolling and let them express what they wanted to express on camera. In China, when I went back in 2018, there were a lot of intimate conversations happening. Yingying’s father only wanted to talk with me off camera. None of that is in the film and I didn’t record them, but these were heart to heart conversations about what he wanted to do after Yingying’s case. He didn’t know what he wanted to do, or what the future of the family was. They were still struggling. Even today, a year after the trial they are still struggling. So, it was important to prioritize their feelings and their privacy, to show respect to them throughout the process.

Filmmaker: Did her parents have any influence over how you told the story?

Shi: I never knew what was going to happen next, so I wasn’t sure about the structure of the film. But they knew it was a human story from the beginning. Halfway through production, we decided this would celebrate Yingying’s life. We discovered her diary and a lot of her childhood photos and home videos. At that moment, the media attention faded away, so we had an opportunity to highlight Yingying and bring her to life. The parents knew that was the core of the story, so they were quite supportive.

They didn’t ask much. Actually, they didn’t ask anything before we showed them the cut. We were supposed to premiere the film at SXSW but it was cancelled. We already booked the flights and got their visas and tried to fly them here to attend the premiere. We intended to show them before the film was finished, because we wanted to make sure everything in the film was okay with them. But then everything with COVID-19 happened, so I had my friend in China visit Yingying’s parents and show the film on her laptop. Shilin Sun and I Skyped in to stay with the family and watch the film virtually. The film was very difficult for Yingying’s parents to watch. Yingying’s mom started sobbing as soon as the film started. Yingying’s father didn’t really say anything while watching, but they would both talk about people they knew in the film. I was really nervous to show them because there are some family conflicts in the film. In Chinese culture, we don’t really want to show family affairs to the public, but Yingying’s parents were actually okay with that, because they felt it was just what happened, it was the truth.

The one thing they did ask was about the civil lawsuit against the university. They wanted us to have more on that. But from my perspective, we wanted to make sure the film centered on Yingying herself and I didn’t want to end on the lawsuit. So, I added a text card at the end after Yingying talks about her dreams, and her boyfriend [Xiaolin Hou] about how she is an ordinary and extraordinary girl. Yingying’s parents, as participants of the film, basically trusted us in the way we told the story. Actually, next week we are going to show the film in China. That’s something they wanted to do. We wanted to bring Yingying’s story to more people, for them to memorize her and the journey of her family. It will screen in the city where Yingying and her boyfriend went to college and met each other, so that will be very meaningful to them.

Filmmaker: I know you saw similarities between your life and Yingying’s even before filming, but when did you realize you would become an integral part of the story structure?

Shi: I never thought I was going to be part of the film in the beginning. I think the first time I thought about it was at a work-in-progress screening for Kartemquin Films in Chicago. That was just a twenty-minute sample, a student film. I put together footage I shot over ten weeks. Most of the footage was of the family, and there were questions from the audience asking me if I was exploiting the family. In that sample, you couldn’t really tell what the film was going to be about or who was making the film. So, I started to think about if I should make it clear who is behind the camera.

It would be very different if it wasn’t me, someone with a similar identity to Yingying, making the film. If it were an outsider or American journalist making the film, it would feel quite different. Later on, as I got more involved with things, the parents started to talk to me directly on camera. There were a lot of emotions and facts that could not be told without my experience. Also, the more time I spent with Yingying’s parents, colleagues and friends, the more I learned about who Yingying was. Basically, she was just amazing. When I read her diary, I was totally blown away, because a lot of her handwriting, her feelings, were the exact same feelings I had when I first came here. I just resonated with her so much.

In the film I also tried to bring in the perspective of an international student, and as someone from that community it works for me to tell that perspective. We didn’t think to include me in the film until postproduction, so we didn’t have much footage of me out filming, but gathered all that we had.

Filmmaker: You do the voiceover of Yingying’s diary yourself for apparent reasons, but why in English?

Shi: Yingying wrote both in English and Chinese, but we decided to translate everything in English for multiple reasons. I really wanted to show Yingying’s story in America, to the English-speaking audience. In China this is already a high-profile case, everybody knows what happened and how difficult it was for her parents to search for her in the US. But in the US, not many people know about their journey. Also, just visually, because we animated her handwriting, if I narrated in Mandarin, we would still need to put subtitles. It would have been difficult for people to read both at the same time, and we knew we needed to show Yingying’s handwriting.

Filmmaker: You do show the murderer in this film. How do you bring him in without that taking away from Yingying’s story, especially considering his feeling that the volunteers and media attention surrounding the case are for him, and not her?

Shi: It was one of the challenges throughout the whole process. We actually interviewed the prosecutors, the FBI, etc. We could have made a true crime film, but decided not to. We don’t want to glorify someone like him. The way we cover crime stories nowadays, we always forget about victims. Those people get left behind and eventually get dehumanized under the label of victim. We wanted to make sure that the audience understood the basic facts of the crime. Only when the audience understands how heinous the crime is will they understand how big the loss of Yingying’s life is. So, we had to include basic facts, but not go too far in that direction. We did have some of the secret recordings, where the defendant talked about how he killed her in detail, but we didn’t include his own words. It was me who describes the process briefly in my own words. Through my voice, I can somehow tone down the heinous crime, but still let you know exactly what happened.

There’s a segment in the film where he talks about how hard Yingying fought back. It was our intention that even when he talked about the crime, it’s about how hard Yingying fought for her life. That’s still part of her personality, and we are still showing her even in her last moments of her life. There was a time when we thought about talking to his friends and family, but we ended up not doing that, because this is a film about Yingying.