Back to selection

Back to selection

“I Wanted the Film to Feel Like an Online Dating Hall of Mirrors”: Pacho Velez on his Sundance-Debuting Searchers

Searchers

Searchers As someone who came of age at a time when looking for a potential partner(s), be it for a lifetime or one night, was less a neat calculated exercise and more a messy spontaneous surprise, I’ve never quite understood the appeal of online dating. Seeking love and/or sex via swipe just always seemed creepily clinical and controlled, cold and robotic — about as sexy as in vitro fertilization to my mind.

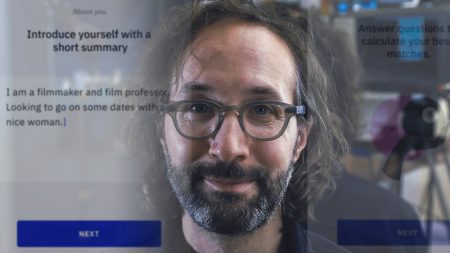

And yet watching Pacho Velez’s Searchers, an exploration of online connecting through the eyes (literally, as Velez’s Interrotron-style setup allows his characters to look directly at us as they navigate their favorite dating apps) of New Yorkers during the physically distanced COVID summer, had me unexpectedly riveted. Through a variety of participants — spanning age, sex, sexuality, gender-identity and race — we become privy to the strangest of sociological experiments. Rather than any deep dive into the state of our collective love lives, or a statement on the often elusive promises of big tech, we get a fascinating visual realization of process itself. By allowing the searchers to focus intently on the task at hand (and not the camera in their face) we’re able to watch in real time how physically reaching out, tapping — and attempting to touch another human being through an inanimate object — radically alters natural behaviors, and thus perhaps even our desires.

Which, inevitably, only led me to more questions. Luckily, Filmmaker was able to reach out and connect with the director behind Searchers as well as 2013’s Manakamana (co-directed with Stephanie Spray) and 2017’s The Reagan Show (co-directed with Sierra Pettengill) just prior to the film’s January 30 online premiere in the Sundance Film Festival’s NEXT section.

Filmmaker: I read that Searchers emerged from over 75 encounters with a wide range of New Yorkers. So how did you get all these folks to participate, and how did you ultimately narrow down the characters to those we see onscreen?

Velez: Browsing online dating apps is such a personal activity that I only wanted to talk to people who wanted to talk to me. I found these people in different ways — through friends of friends, social media posts, notices on websites, reaching out over apps, etc. My diligent co-producer Milo Borsuk and a small army of students and recent alums from The New School (Erin May and Paige Simunovich deserve special mention) spearheaded much of the work.

After shooting with about 50 people our editor Hannah Buck winnowed the footage down to a “manageable” four-and-a-half hours. Hannah and I then watched and rewatched her assembly. When two characters felt like they were making the same point we kept the one who stated it most compellingly. When we felt that something was missing from the film I shot more footage. Eventually Hannah had to step away, and I finished the film with another talented editor, Scott Cummings. Over the last month we whittled the film down to its final form, featuring the most charismatic and emotionally-present interviewees – all presented against the backdrop of a city trying to make the best of its COVID summer.

Filmmaker: How did you arrive at the film’s conceptual framework? Having the searchers look directly into the camera as they swipe “us” while divulging what they’re looking for (and not) turns the viewer into a participant in the online dating game as well.

Velez: From the start I wanted the film to feel like an online dating hall of mirrors, with the characters making judgments about the dating profiles and the audience making the same judgments about the characters. Are they stylish? Do they make me laugh? Would I be excited to meet them IRL?

Once production started the reality of shooting during a global pandemic interrupted a lot of my plans. Rather than being frustrated, though, I looked for ways that these new circumstances could be part of the film. We started shooting interviews outdoors and also filming glimpses of public intimacy for use as transitional moments. These elements inject the film with some of the verve that makes living in NYC so much fun.

Filmmaker: Searchers actually made me reflect on one of your prior works, The Reagan Show. I’ve often wondered if Reagan’s spending so much of his adult life in front of the camera caused him to lose any sense of true self, to actually become his Hollywood persona. Have you thought about technology’s ability to not only shift how we present ourselves to the world, but to change who we are?

Velez: Yes, absolutely. Searchers is a group portrait of online dating in NYC, but on another level the film shows how the internet, that “digital looking glass,” absorbs our attention and shapes our view of the world. Life is filled with technologies of self-regard, media that permit us to see ourselves: videos, still photographs, even mirrors. People don’t think of mirrors as technology, but before 1835, when a German chemist developed a process for applying a layer of metallic silver to glass, it was normal to go the day without seeing oneself. Imagine living like that.

Filmmaker: Listening to some of the searchers, specifically one of the older straight white men, made me worry that with online dating we transform a person into an abstract profile, just another product to be obtained. (But perhaps that’s true offline as well, as there have always been meat markets.) Were you aware of this human commodification aspect during production, or even through your own personal experience?

Velez: Making the film I wrestled with my own feelings about online dating apps. There are many positive aspects to them, but as you point out, they have their downsides as well.

In 1973 Richard Serra and Carlota Fay Schoolman, writing about another ostensibly free technology, broadcast television, made the point that, “It is the consumer who is consumed. You are the product of t.v.” In a market economy, if we’re not paying to use a service then someone else is paying the service for access to us. Dating apps have been designed so that the more we engage with them — the more data we give to them — the more we turn ourselves into their product (for sale to other tech companies, and also to each other, via premium service tiers). It’s certainly a dispiriting thought, but one tempered by the stories of joy and intimate connection that I heard while making the film.

Filmmaker: Interestingly, out of all your searchers the young gender-nonconforming participant, and also the young cisgender woman and her friend looking for sugar daddies, appeared most satisfied with their dating encounters. Perhaps because they are freed from having to explain themselves, of judgment. (The former seemed downright liberated, maybe the ability to filter allowing for a semblance of protection; while the latter don’t have to pretend to be looking for anything other than an online shopping-like business transaction, for which the internet is the perfect conduit.) Did you find that online connection is just better suited to some segments of the population more than others?

Velez: The thing that really connects the two interviewees you mention (Caroline and little_sailor) is that they’re young, 23 and 20. I teach college students at The New School, and they have told me that they would find it “weird” and “uncomfortable” for a stranger in a bar to ask for their phone number. But they navigate dating apps with the same comfort and confidence that earlier generations had flirting at TGI Fridays.

For older users online dating rituals are less intuitive. I admire the courage of people like Helene. who at 88 years old is trying to date for the first time since she was a teenager. If I reach her age, I hope that I’d have that same energy and positivity tackling new experiences.