Back to selection

Back to selection

“The History of Your Community Affects Who You End Up Becoming”: Lyle Mitchell Corbine Jr. on Wild Indian

The effects of trauma brewed and replicated over generations serve as dramatic engine for Wild Indian, a film about the radically diverging paths of two boys from the Ojibwe people after a fatal gun incident. Making his feature debut, director Lyle Mitchell Corbine Jr. tapped into his tribe’s own ancient storytelling and recollections from family members, as well as his own, to carve out the story of Makwa and Teddo in two different storylines. The former character, a victim of parental abuse, grows up to rebuild his stoic identity around career success and material wealth, while the other falls into a life of crime but still is capable of empathy.

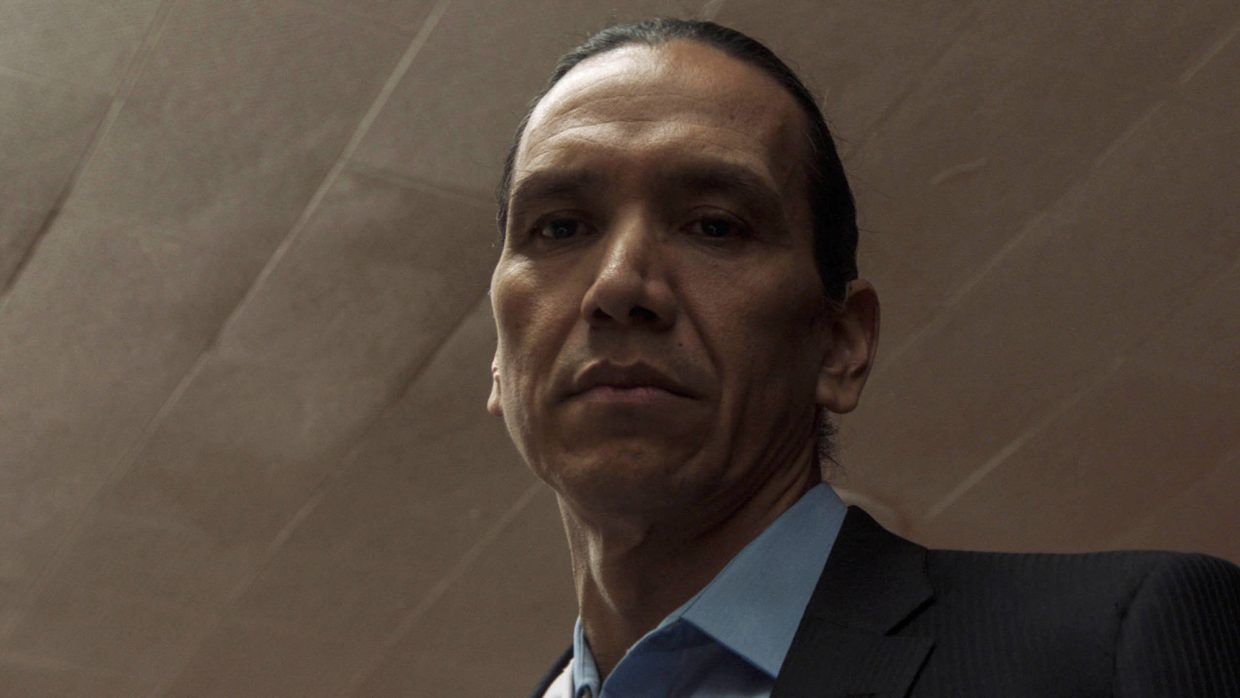

As Makwa, actor Michael Greyeyes exudes a chilling inexpressiveness and propensity for violence that fester under a pristine exterior. His controlled performance, as someone unable to project recognizable human emotion, drives this treacherous character study with fascinating moral ambivalence. To conceive the final version, which premiered at Sundance Film Festival in January, Corbine Jr. tailored the film to the qualities of the actors playing Makwa in both planes (Phoenix Wilson plays him as a teen) and opted for a visual approach that prioritized the actors’ faces within the frame. For the filmmaker, putting forward a Native story, embedded with these qualities, reflects his personal understanding and artistic interpretation of where he comes from.

Filmmaker chatted with Corbine Jr. about the many drafts the project underwent to reach the screen and how the Sundance Screenwriters’ Lab became the key an important casting decision. Wild Indian is in release now from Vertical Entertainment.

Filmmaker: The film is bookended by scenes that take place in an ancient era, which seem to expand the scope and ramifications of the story in the present. What was theintention behind these moments?

Lyle Mitchell Corbine Jr.: I was obsessed with the way that archetypal stories manifest themselves throughout time and then modern day, as well as how these historical events have reverberations throughout time. The idea of recognizing yourself in a biblical story, like that of Cain and Abel, but also reconciling yourself with the history of your people was something that I wanted to contextualize. With these two characters and their place in the world of the story, I wanted to contextualize why they are the way they are.

Filmmaker: The fact that these prologue and epilogue are detached from the reality of the narrative adds to their mythical weight.

Corbine Jr: Exactly. I wanted it for it to play with time and something that was maybe a little more intangible in the form of a legend. That Ojibwe man is from a story that I heard growing up that said when Ojibwe people would get sick, they would head upriver, and then if they got better, they’d come back. A lot of times they would never come back. That was when settlers came over native didn’t have immunity immunities against diseases, so they would get sick and to keep their community safe they would leave until they were better. Most of the time they’d didn’t get better.

Filmmaker: There’s another time jump in the narrative, from the day that marks the boys’ lives to them as adults. The way you play with the timeline enhances how we perceive their transformation. Tell me about this second leap forward.

Corbine Jr: If you’re going to jump in time 400 years or 200 years, the idea is you might as well jump in time another 30 and just to track, it just felt like that was the nature of the story because of the way that your childhood affects who you are as an adult and your family. I suppose the history of your community also affects who you end up becoming or how you ended up coming into the world as well.

Filmmaker: The film is a study on Makwa, more so than on Teddo. Is he the embodiment of multiple experiences you were familiar with or perhaps on someone specific?

Corbine Jr: It’s not based on anyone specific. For me he embodied somebody that had put up this emotional armor and ran away from who he was for so long, and even had a hard time empathizing with other people. It wasn’t based on anyone that I knew. It was just a psychological framework that I was aware of regarding people who have gone through severe trauma.

Filmmaker: Religion is present in the film in relation to the character’s guilt, and as you mentioned, how there are similarities with the story of Cain and Abel. Why was it important for you to grapple with this subject in Wild Indian?

Corbine Jr: Catholicism perpetuated itself onto certain reservations and native communities, coming in and setting up residential schools, but also tribal schools in less severe cases. For instance, my grandpa grew up speaking Ojibwe as a first language and when he went off to this missionary school on our reservation, he ended up essentially having the language beaten out of him. He was punished for speaking his language in school. By the time he was my age, I don’t think he spoke it anymore. That’s a very personal thing to me. I’ve seen it manifested in my life and I’ve heard the stories firsthand, how these institutions affected individuals.

Filmmaker: What was your writing process, or journey, to craft this screenplay? Was it developed over a long period of time? Tell me about the arc of its creation.

Corbine Jr: It came together over six years or so. I started writing it in 2014 and then it was just a story of a mid-twenties person living in California and having his family from the reservation come and visit him. He felt resentful of the presence of his cousins. That’s all the story was initially. It was almost like a comedy-drama type of thing. But the more I wrote on it and the more I thought about it, I realized I was writing about trauma, so I started including details, like the murder and these plot points that really help explore and raise the stakes of this relationship between the Teddo and Makwa.

Filmmaker: I’m sure it went through a lot of transitions over that time.

Corbine Jr: There were about 20 drafts. I went through the Sundance Screenwriters Lab. There are thousands of applicants every year and I was fortunate enough to get chosen for that. I met a lot of really great mentors who helped me craft the story and try to figure out my own voice and what I was trying to do creatively.

Filmmaker: How did Michael Greyeyes, who gives a knockout performance, factor into the conception of the film. Was he in your mind as the ideal actor for this part from the onset?

Corbine Jr: Short answer, yes. But Makwa was a tougher character to figure out. I always knew that I wanted Chaske Spencer for Teddo. I knew he would be just an incredible heart to the film. You just see him and you empathize him, no matter what he’s got on his face. But Makwa in the script was very peculiar, an almost alien presence and trying to figure out who would physically embody that was a process. Once I started thinking of Michael Grayeyes, Makwa started to make more sense. I rewrote it for him and got the script to him. He was very enthusiastic about it and understood what I was doing. I crafted the story and the character around him.

Filmmaker: When you say that you rewrote it for him, what changes did that entail exactly?

Corbine Jr: Well, the idea was always that the character had a certain iconography about him. Makwa was always supposed to have a very distinct Native face that anybody in the world could see Michael in this movie, even if they didn’t understand English, and be like, “Oh, that’s a Native American man.” Michael very much exuded that. But there were iterations of the script where maybe Makwa wasn’t exuding the kind of power and confidence that Michael embodies. Once I started thinking of him for the role, the character started making a lot more sense. I was able to craft it around his, onscreen presence and the way that Michael carries himself as a performer.

Filmmaker: In directing him were you specific about how you wanted him to deliver of his dialogue, I feel like that it’s in how he expresses himself to others that we can infer the lack of human empathy. There’s no emotion to his words.

Corbine Jr: We often had only two takes, sometimes three, if we had a little bit of extra time, which wasn’t really ever. So it was really Michael’s performance in the minutia working with things we had talked about before we ever got on the ground. We talked about how this character knows the right things to say, and in certain situations, but he doesn’t know how to say them. He’s kind of like an alien. He’s unfeeling and then we see little cracks in his persona as time goes on. For instance, in the hospital scene with Lisa Wolf’s character. We were thinking of him as this person that has put on so many airs and has this way of operating in the world that expresses itself as this strange pretentiousness, what was a really fun way to start thinking about him as a real person.

Filmmaker: In the first seen with Jesse Eisenberg, who plays his coworker, it seesm as it Makwa wants to assert his power in a strange manner.

Corbine Jr: Yeah, he knows how to push buttons and he likes to do that. His relationships are only of value to him so far as he can use them to further his own wishes, so in that scene with Jesse. He wanted to put him in his place and make him feel uncomfortable and awkward. And he got that out of him.

Filmmaker: On the other hand, you have Phoenix Wilson, who plays Makwa as a teen. There’s something very striking and almost frightening about his presence. And there seems to be a strong through line between his performance and that of Michael Greyeyes. How did Phoenix come into the project and how did you know he was the ideal young actor for this role?

Corbine Jr: Phoenix is amazing. He showed up and I knew he was going to be able to bring this value to the film that I never could have planned. He has such an unnerving presence in the film. It happened when we did the Sundance director’s lab in 2018. We sent out a casting notice to find a young Makwa and at the time the character was 12. But when saw this Phoenix’s audition I knew he looked like my cousins. He had this softness about him and I knew that that was the kid. When he came in and we worked with him at the director’s lab, he was so professional and a very good actor for his age. I knew we weren’t going to be able to find anyone else that could bring that kind of presence to it, even if we searched the whole country. So as time went on, we ended up shooting “Wild Indian,” the real movie, almost two years after the director’s lab, so I decided to rewrite the character to be older, so that we could cast Phoenix.

Filmmaker: When you were writing the piece, how did you engage with the very different paths that Makwa and Teddo follow, both emotionally and visually, in relation to their specific trauma?

Corbine Jr: It was one of those things where I was in like this strange stupor writing the movie, thinking of my own individual trauma, and trying to describe the feelings I had about that individual trauma and trying to describe it to a character that’s going through much more terrible things. Visualizing the film later on it was just a process of trying to find the right performance to do it, but then also being able to elevate those performances visually with somebody like my director of photography Eli [Born], who knows how to shoot very severe looking images.

Filmmaker: On that note, film mostly unfolds in close-ups of faces, whether their expressions reveal or conceal what they feel. Was this a conscious mandate for you and your cinematographer when discussing how to frame them and what to highlight?

Corbine Jr: We shot the film in Oklahoma. We were initially going to shoot in a part of Oklahoma that looked somewhat like Wisconsin, but because of budget reasons, we weren’t able to travel up there to do it. I was having a bit of a tough time visualizing the film, because initially there was a lot more nature in the film, a lot more specificity to the place. We weren’t able to include that. So I talked to my DP and my production designer before we ended up shooting and said, “The film needs to primarily exist right here.” [] I hate close-up movies, but we need to figure out a way to make it visually interesting and keep the movement dynamic and frame it in an interesting way while making sure all remains from the middle of the chest to the top of the head. That was how we operated. We had 17 days to shoot the film and we tried to prioritize that kind of framing and making sure that the specificity of the performances was captured in that language.

Filmmaker: In the present nature is replace by Makwa’s new life, inside sleek, urban spaces.

Corbine Jr: I wanted that contrast of somebody who completely rebuilt their life and he’s placed a shell around him with things that he thought he needed to be a full person. The visual contrast of that was definitely the way that I wanted to help elevate and tell the story of that arc.

Filmmaker: With the current on Native stories, do you feel this is the right moment for a film like Wild Indian to be released and offer a different perspective than what the comedy shows centered on Native characters have offered?

Corbine Jr: We’ll see how the release of the film goes. The response has been very good. We had a great New York Times review and we’re pretty high up on the Tomatometer on Rotten Tomatoes. I hope that that translates into finding a specific audience. There seems to be a lot of interest in the industry about finding interesting Native stories, specifically for me to be involved with as well. The response at Sundance among the Native people who saw it was very positive. There hasn’t been a film quite like this, for better or worse. So let’s see what the long-term thinking is, but it’s been very positive and I think people are supportive of me coming from where I come from and of me telling a personal story.