Back to selection

Back to selection

“We Set Out To Make a Documentary in Six Months, Get the Music Out There, Play at Sundance and It Ends Up Taking Us Six Years”: Directors Richard Peete and Robert Yapkowitz on Karen Dalton: In My Own Time

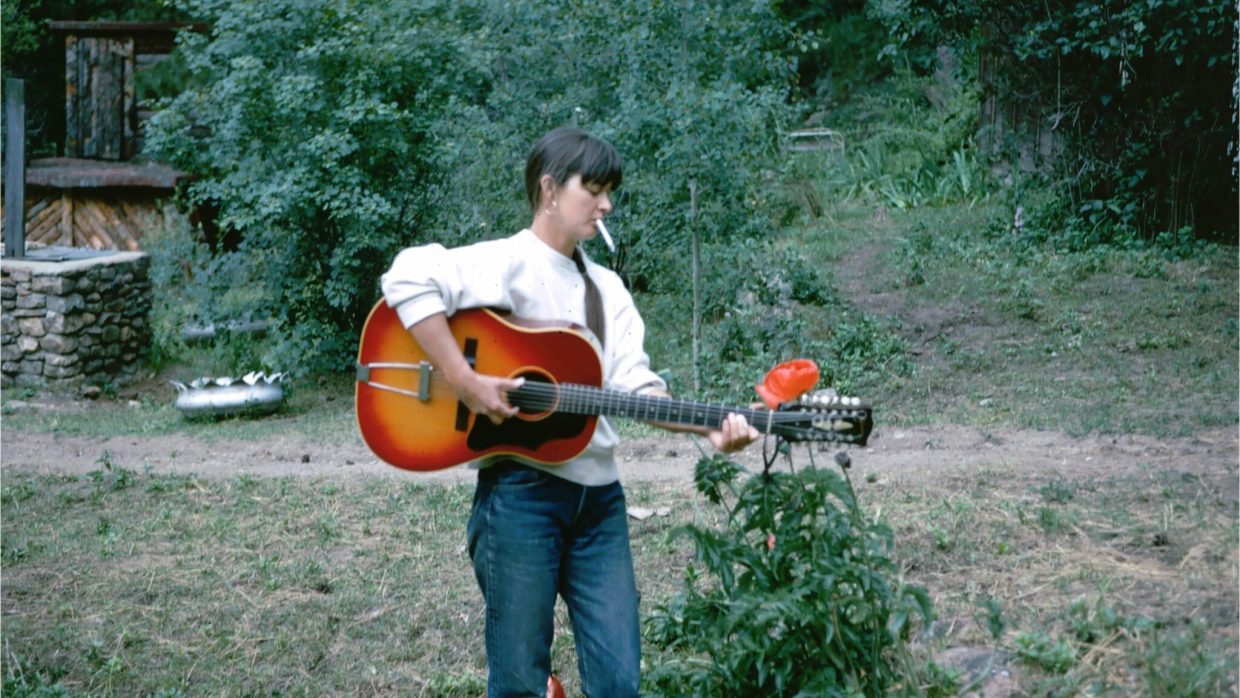

Filmmakers Richard Peete and Robert Yapkowitz were deep in Missouri, working in the prop department for Debra Granik’s Winter’s Bone, when they both became consumed with the legendary 1960s-era folk singer Karen Dalton. The artist, who died of AIDS in 1993, only 55 years old, was famously described by admirer and peer Bob Dylan as someone who “sang like Billie Holiday and played guitar like Jimmy Reed.” Her hallowed status on the Greenwich Village scene that launched Dylan and many others never elevated her to mainstream success. Drug addiction and emotional turmoil took a heavy toll, yet Dalton left behind an intense and influential legacy that has made her an essential touchstone for succeeding generations of singer-songwriters across a broad arc of styles. She only released two studio albums in her lifetime – It’s So Hard to Tell You Who’s Going to Love You the Best (1969) and In My Own Time (1971) – but that slender catalogue has nourished a fandom far beyond what she enjoyed in her own day.

The songs, nearly all of them covers although Dalton was a prolific writer, were plenty to hook Peete and Yapkowitz. “We fell in love with her on that trip,” Yapkowitz says. Years later, the pair tapped into that passion when they chose a topic for their first project as co-directors. Karen Dalton: In My Own Time, currently playing at New York’s Film Forum, eschews the typical parade of contemporary talking heads (mocked in Edgar Wright’s The Sparks Brothers) to focus on conversations with the performer’s family (her daughter, whose feelings and memories are layered and complex, and granddaughter, who is unabashedly stoked), former companions and musical fellow travelers, including the impish Peter Stampfel (of the Holy Modal Rounders) and guitar wizard Peter Walker, who also served as the keeper of Dalton’s archive. It was in that archive that the filmmaker’s came across Dalton’s journals, intimate and unguarded documents that do much to infuse the project with the singer’s soul. Although the singer-songwriter Angel Olsen, one of Dalton’s artistic inheritors, reads the entries used for the film, Peete and Yapkowitz took to heart the single note sent them by the executive producer who came onboard as the film was heading for a final draft. That would be the German filmmaker Wim Wenders, who advised them to use the journal as a throughline for the story, emphasizing Dalton’s handwriting.

In a recent conversation conducted via Zoom, the filmmakers spoke about the remarkable archival work that animates Dalton’s life, the unavoidable influence of the Coen Brothers’ existential folk-era drama Inside Llewyn Davis, and the film’s lively evocation of 1960s drug culture.

Filmmaker: If an artist who dies too young these days, they’re so fully documented. But to tell the story of Karen Dalton, you really had to go digging. The archival work in this film is extraordinary.

Peete: It was really fun and a treasure hunt. When we originally started to make this film, Rob found Karen’s daughter Abbie, on Facebook, and found the restaurant that she worked at, and ended up calling the restaurant, and called the restaurant a few times until he got Abbie. He told her we wanted to make this film and her reaction was, “Oh, people have tried before and failed, because there’s no footage of her, and I don’t think people are really interested in seeing a movie on my mom.” But we were persistent and went to see her, and through scouring the Internet, and working with some really good archivists, we were able to uncover some really incredible footage and audio of Karen that people had never seen or heard before. It’s cool that Karen lived in a period when things weren’t documented all the time. Karen would just get up and leave and not tell people where she was going. It’s confused always. People were telling us they lived with Karen in 1965 in L.A., and someone else was telling us they lived with her in Woodstock at that time. It was fun piecing everything together.

Filmmaker: What was the treasure hunt like? What was your strategy?

Yapkowitz: A lot of it started with talking to people who knew Karen. The footage we have of Karen on the television show Beat Club, her guitarist Dan Hankin, who’s featured in the film, said something along the lines of “we played a French TV show on the Santana tour.” Which is not correct. We didn’t find that footage, but it led us to Beat Club, essentially going through with our archivist Elizabeth Hinson old listings in TV Guide. We realized Santana played Beat Club, and it lined up. Through that, we found there was Karen Dalton performance on there. Once we knew it existed it was another year before we saw it.

Peete: We had heard of footage being shot during the Montreux festival, and couldn’t find that at all. One day this summer we delivered the film, like finally finished it, and the very next day there was new footage of Karen that popped up on YouTube, And then it was gone the next day. But we had the YouTuber’s screen name and were able to contact him. It took us a few weeks to twist his arm to give us the contact information to where he got it, but we ultimately had to open the edit back up and incorporate the new footage and get the rights to it. It feels like the hunt never stops, even once the film is done.

Filmmaker: I’m sure it felt like a quixotic quest at times.

Peete: We’d also heard that Karen was an avid recorder, and she had made hundreds, maybe thousands, of cassette tapes, she was constantly recording. We had to find these tapes. The rumor was that – and this didn’t make it into the film – soon after Karen passed away, she had a shed behind her house that burned down and all of the cassette tapes were destroyed in that fire, a separate fire than the one that happened in our film. So Rob and I went up to Woodstock and we found the mobile home she had lived in and we broke in through the window and scoured the place trying to find the tapes. We could never uncover them.

Yapkowitz: We knew those tapes existed — [the ones we feature with] Bob Fass from [the public radio show] Radio Unnameable and Karen talking — in some form for such a long time before we got [them]. It was while Bob’s archive was in the process of going to Columbia University. We talked to his lawyer. Then we had to get in touch with Columbia. Then we had to wait a year or two for Columbia to digitize everything. It was a lot of following these bread crumbs.

Filmmaker: How many years did it take?

Peete: We came up with the idea almost seven years ago now. It was right after the Townes Van Zandt documentary Be Here to Love Me came out. I think the Daniel Johnston documentary had been out also, and we were hanging out at a bar and realized all of Karen’s peers were on the jukebox but Karen wasn’t. So we set out to make a documentary in six months, get the music out there, play at Sundance and it ends up taking us six years to make it.

Filmmaker: Of course, there was a trove of material that later perished in another fire that you did get to. How did you discover that?

Peete: We went up and met with Peter Walker. He was the first person we interviewed We ended up interviewing him for four days. We have 150 hours of Peter Walker, in case you ever want to make a documentary on Peter Walker. We became friends with him and we scanned a bunch of stuff. Rob went back up about a year later, scanned a bunch of archival, smoked some weed and played music with all the locals up there. It was pretty soon after that that Peter’s home burned down and destroyed all of that stuff. We were the ones who archived everything. We’re trying to figure out what to do [with it] … to get them out into the world.

Filmmaker: I don’t think the film would work without it.

Yapkowitz: It was a huge part of giving Karen a voice.

Filmmaker: I think those elements helped the film capture some of the real-life gravitas that the Coen Brothers were going for in Inside Llewyn Davis. The downer part. Here are these geniuses in a scene that’s going to produce the most acclaimed songwriter who ever lived – Bob Dylan – and a number of people who were successful for a very long time, and then all these other people who fed those people with their own genius but remain obscure, way out of pop culture’s orbit.

Yapkowitz: That movie was an influence for sure. It’s the same ethos. It’s like these people who are so devoted to what they’re doing that they can’t see beyond their own emotions. It’s hard to describe what that is, but it’s definitely very much part of it.

Peete: Don’t you think there was a character in the film that was based on Karen loosely?

Yapkowitz: I think it’s more the look. There’s a shot in Llewyn Davis where it’s Justin Timberlake and Carey Mulligan and another gentleman and they’re singing, the three of them, onstage and Carey Mulligan has the black hair and the bangs and the turtleneck on, and she’s modeled after a photo of Karen. And they dress her like Karen throughout the movie.

Peete: We just partnered with a company to do a narrative adaptation of Karen’s life. Llewyn Davis is a really big inspiration.

Filmmaker: I was really impressed with some of the interviews, which were so frank – especially the candor about drug use. That whole story about Karen having a seizure and ripping a sink off the wall, and then rolling right into a jam session, as told by Peter Stampfel. It’s so matter-of-fact, and even kind of hilarious. That may be shocking to some people who have no cultural memory of the 1970s.

Peete: We tried to become friends with the people we talked to beforehand so it felt comfortable. I think it can seem tragic. But I’ve used speed before and when I tell stories with my friends about what it was like, it’s fun. People were comfortable talking about how crazy and fun those times were – not tragic. It was something we leaned into.

Filmmaker: It reminds viewers that there once was a counterculture, and things were much looser in those days than they are now.

Peete: Everybody was using back then.

Yapkowitz: People who didn’t live through it have images of the ‘60s and ‘70s and think, oh it was crazy people were on drugs. But they don’t realize how off the rails some people were in terms of their drug use. People were reckless. They didn’t know much about what they were doing at the time.

Peete: Is the story about Karen peeing in the closet gone?

Yapkowitz: That’s gone. That was more of an alcohol thing. That’s because she was pissed at somebody. Literally.

Peete: We had so many of those stories that we just couldn’t include all of them.