Back to selection

Back to selection

“It’s Also a Story of the Power of the Media to Shape a Narrative in Ways That Do Disservice to the Truth”: Traci A. Curry on Attica

Attica

Attica Attica (releasing in theaters on October 29 and on Showtime November 6) is the latest from nonfiction national treasure Stanley Nelson. Along with his co-director and producer Traci A. Curry, a longtime MSNBC producer, the Firelight Media co-founder and MacArthur “Genius” Fellow, who has previously chronicled organizations from The Peoples Temple to The Black Panthers, has now chosen to tackle a very different kind of institution: The prison industrial complex that was captured in one word and broadcast round the globe on September 9, 1971.

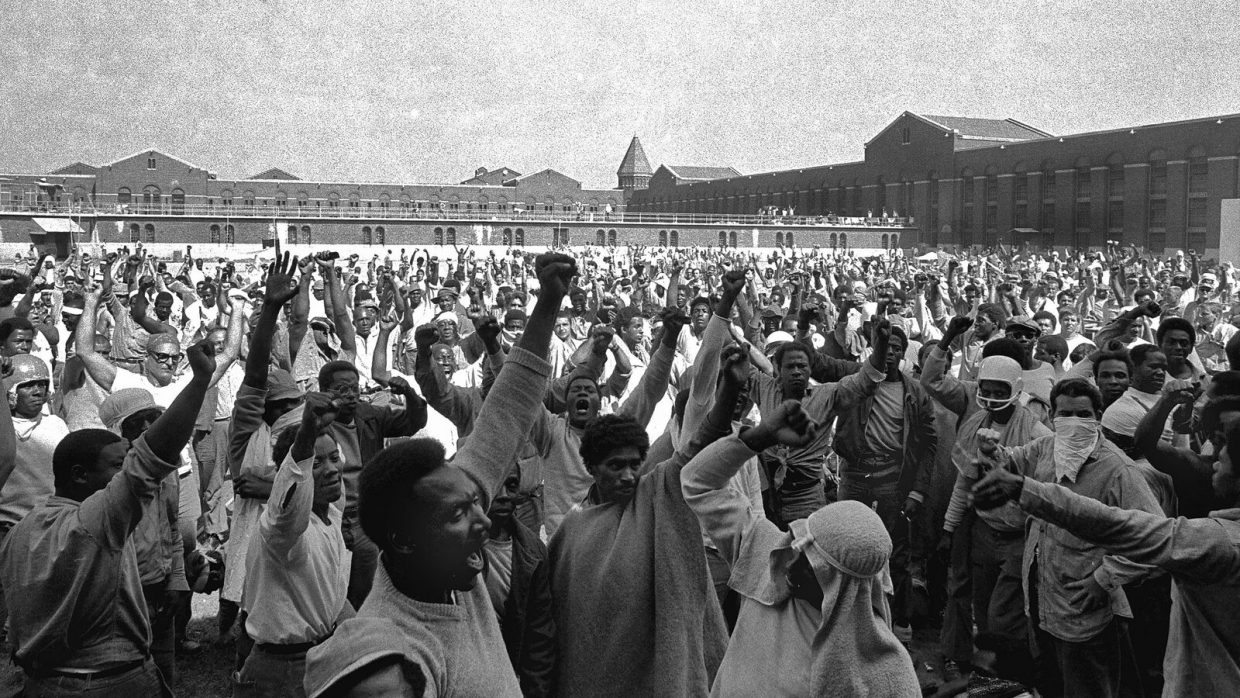

The titular uprising that occurred at that correctional facility in Attica, NY a half century back was a five-day, real-life, made-for-TV event meticulously covered — from the seizing of the yard by 1200 inmates to its bloody end that left 29 inmates and 10 hostages dead — by cameras both inside and outside the prison walls. And Nelson and Curry certainly make deft use of that footage (right down to the CCTV). But the team then delves remarkably further, interviewing not only the formerly incarcerated whose act was a cry for basic humane treatment, but also the families of the corrections officers that were left to grieve without any straight answers from the government to this very day. Indeed, when it comes to the largest prison rebellion in US history, which resulted in “the deadliest violence Americans had inflicted on each other in a single day since the Civil War,” only one thing is crystal clear. All the cameras in the world can never tell the full story if the bigger picture remains nefariously obscured.

A few weeks after the doc’s opening night premiere at TIFF, Filmmaker caught up with Curry — a two-decade industry vet who’s also the founder and owner of production company B.Free Media — to learn how the duo went about bringing fresh sunlight to a still sordid tale.

Filmmaker: So how did this film originate? Did the 50th anniversary of the uprising bring a sense of urgency to the project?

Curry: Stanley is probably the best person to answer about the origins of the film, though I wouldn’t say that the anniversary created any urgency per se. If there were any “urgency” related to the 50 years, I’d say it was more so the recognition that there are fewer and fewer people still living who were at Attica during the uprising, and who are willing and able to speak about their firsthand experiences. There are people who were there who actually passed away during the process of making the film. So it really just highlighted why it was so important and necessary to find and document the experiences of as many people as we could who lived it and could still tell the story.

Filmmaker: How did you choose which characters to include in the film? Were there any folks you reached out to who declined to participate?

Curry: My initial intention was to include every single person I could possibly find who was at Attica prison during those five days, and whose lives were touched by what happened. It was clear early on that there were categories of people who we very much wanted to hear from: the prisoners; guards and civilian employees who were held hostage; observers; media; and members of the community and families who had gathered outside. I wanted to hear from them all in this story. That includes the guards – several of whom I spoke with extensively and planned to film. Ultimately, though, they declined to take part.

Filmmaker: The media certainly played a decisive role in shaping the Attica narrative. So were there particular aspects of that story you felt merited further investigation — and perhaps even required revision?

Curry: In some ways, the media is everything to this story. We quite literally could not have told it without the media and all of the film that was captured inside of D yard during the days of the rebellion. There had certainly been other prison uprisings in the country at that time, and specifically in the state of New York in the year before the one at Attica. But the reason we are still talking about it all these years later and made a film about it was because one, the way it ended. But also because it was the first time the public was able to see and hear from the prisoners about their experiences in their own words. And that is entirely because the prisoners had the temerity to demand that the cameras and reporters be allowed into D yard.

Yet it’s also a story of the power of the media to shape a narrative in ways that do disservice to the truth, particularly when there is an over-reliance on access journalism. As we see at the end of the film, the media reported the information that came from a single source in the prison administration saying that the prisoners killed 10 of the hostages – which of course turned out to not be true.

Filmmaker: The archival trove, including the CCTV footage from inside the prison, is really the visceral heart of the film. But what choices did you have to make when it came to the story structure? What was left on the cutting room floor?

Curry: My background is in journalism and so I understand that there usually comes a time that your darlings must die, which is always a little heartbreaking. There was certainly some of that involved here. There is just so, so much to say about what happened at Attica – both in terms of what was happening in the country and in the prisons that fueled the uprising, and in the long years of legal fights that happened afterwards. But ultimately we had to focus on telling the strongest, most compelling and true story we could with the time that we had – so specifically about what happened during the five days of the rebellion.

Filmmaker: One of the biggest “revelations” for me was the behind the scenes involvement of President Nixon. I don’t even remember hearing about the phone call with Governor Rockefeller that ultimately led to the massacre. So did you hit any walls during your research? Do you think the public has ever really had access to the full story?

Curry: There are still some documents related to what happened that the state of New York hasn’t released to this day. And there are people still fighting for all of that information to be released to the public. But for the most part, I think the Attica story was out there for anyone who wanted to look and see.

There are some really fantastic books out there, including “Blood in the Water,” which was written by Heather Thompson, the historical consultant on the film, and “The Attica Turkey Shoot,” written by Attica prosecutor Malcolm Bell, both of which I’ve read and recommend. There have also been some really great films that have focused on various angles on this story.

But I think one of the goals for this film was to really collect all of the strongest elements of it — these courageous and compelling voices and the footage that just pulls you in — and weave it together into as powerful and impactful a narrative as possible. And my hope is that we have succeeded in doing that in a way that feels like something close to justice for all of the survivors.