Back to selection

Back to selection

Shutter Angles

Conversations with DPs, directors and below-the-line crew by Matt Mulcahey

“We Used the Entire Sensor on the Alexa LF Every Single Time”: DP Greig Fraser on Shooting Dune for IMAX

Dune

Dune Before Dune’s initial release, director Denis Villeneuve compared watching the film on a television to driving “a speedboat in your bathtub.” Beginning today, audiences have another chance to take that speedboat out into open water as the sci-fi epic returns to select IMAX theaters for a limited run.

Cinematographer Greig Fraser was a bit more diplomatic in his analogy. In the December issue of American Cinematographer, he equated seeing Dune in a cinema to dining at a five-star restaurant vs. getting take-out. Ahead of the IMAX return, Fraser (Rogue One, Killing Them Softly, Zero Dark Thirty) spoke to Filmmaker about being a film vs. digital agnostic, his quest to return choices to the cinematographer and how trying to serve every viewing experience is like playing whack-a-mole.

Filmmaker: Dune is being billed as “filmed for IMAX.” ou shot on the Arri Alexa LF, which is one of the IMAX-certified digital cameras, but outside of just the camera choice what does that mean to film for IMAX?

Fraser: What we did in order to shoot our film for IMAX was, we used the entire sensor on the Alexa LF every single time we turned on the camera. Normally if you’re shooting a theatrical production on the LF with spherical lenses, you’ve got to crop the top and bottom because the sensor is a 4:3 shape. So, you’re effectively losing pixels. When you shoot for IMAX [with spherical lenses and a 1.43 aspect ratio], you’re shooting that full LF sensor. So, we shot the entire sensor when we shot with anamorphic then we also shot the full sensor spherically for IMAX.

Filmmaker: If you watched the film on HBO Max—and I’m assuming it will likely be the same for some VOD and physical media releases—the entire movie plays out at 2.40, with the IMAX sequences cropped to that widescreen ratio. I know you want to maximize the theatrical experience on this giant IMAX screen, but in the long run more people are likely to experience the film in that widescreen version. They’re drastically different frame shapes. How do you serve both masters when framing IMAX scenes in 1.43 that also have to work at 2.40 as well?

Fraser: It’s not easy, I’ll be honest with you. I wish everybody had an IMAX screen in their living room and I wish everybody was able to view it the way we intended. That’s my wish, but the reality is that you can’t serve all those masters. It’s a luxury now for people to be able to get out into the theaters. I get it. I’ve got three kids and getting out to the primo IMAX screen is hard, but when you make something you can’t make it with the lowest common denominator in mind. If you start going, “Well, people are going to watch it on their iPhones or iPads.” then [you also have to consider] if they are going to be watching it [on those devices] sitting on the subway or sitting in a dark bedroom. Who knows? You can’t predetermine that. That’s like whack-a-mole. If you fix something for [one platform], it’s going to come up as a problem in another. It’s like you either say, “The IMAX is a bonus.” or you say, “the 2.40 frame is a bonus.” So we had to basically work on the premise that we were making this for the largest format we possibly could and the largest theater we could without wanting to be disrespectful of the audience that will be seeing it in 2.40. There were instances where we definitely had to compromise. Throughout the process of post-production we were able to change the framing to suit the 2.40 for that Blu-ray or HBO Max the best way possible, but it was definitely a compromise. What I’m hoping is that the larger film is bigger than just the framing. Framing is obviously important to me and Denis, but ultimately the bigger picture of the film is more important than those things.

Filmmaker: Most of your recent films have been either the Alexa LF or the Alexa 65. Have you reached a point where you feel like larger formats are almost your default starting point now, whereas for the last decade it’s been 35mm-sized digital sensors?

Fraser: It’s a great question because there are so many companies building new cameras right now. What size sensor should they build? Here’s the thing—if you’ve got a large sensor, you can always crop into that sensor. If you have an Alexa LF or a full frame sensor, if you wanted to shoot something that has a smaller frame, you could. I don’t know if I necessarily start ]with a larger format] now but that is kind of the baseline, I guess.It used to be that 35mm became the standard back in the film days, but I think the second something becomes the standard, there are masses of filmmakers out there who will thumb their noses at that and deliberately choose not to do that standard. If you say, “Now 65mm is the standard.” you’ll have filmmakers young and old who will be like, “Then we’ll shoot 16mm.” And I love that, because it means there are people upending what those norms are.

Filmmaker: At the tail end of the Dune shoot, you got some Alexa LF prototypes in?

Fraser: We did indeed. Arri sent us a prototype to try, knowing that we were going to be heading into the desert. It certainly didn’t let us down, I can tell you that. There’s a bit of handheld [in the Arrakis desert scenes] and it really helped us to be more nimble. It’s just a smaller form factor so I could hold the camera for a longer period of time. It’s a great camera. There are a number of things about it that are really useful for a production. It has built-in ND filters where I can quickly change the NDs internally without having to slap stuff on the outside of the camera as the sunlight is coming up or dropping down, whichever was the case.

Filmmaker: Since you mentioned ND, there’s a behind-the-scenes shot of you in the desert with 10 stops of ND on the camera, which seems like a lot.

Fraser: You’re right about the ND and therein lies a big part of the problem when you are using a digital format rated at 800 ASA. You’re going to need extra ND [as opposed] to shooting 50 ASA daylight film stock. That’s four more stops of ND that you’re going to require in the camera, and anything you put in front of the lens automatically takes away part of why you’ve chosen that lens in the first place. The Mini LF uses rear-mounted ND, which I feel is a lot better [than placing the ND in front of the lens]. A big part of the process for us when we were choosing NDs was choosing filters that had neutral color density. A lot of IR [Infrared] NDs have a color when you start to get into the 1.5 range. So, we had to choose NDs that did not have that color. We used Firecrest filters.

Filmmaker: After shooting on location in Jordan and on the stages and backlot at Origo Studios in Hungary, you went to Abu Dhabi with a much smaller crew to shoot some of the Arrakis scenes. How did you control the sunlight out there with that smaller footprint?

Fraser: We made a decision in Abu Dhabi not to take our electrics department, who normally would help put up butterflies and negative fill and bounce and all those things. Once you take a light, you need a generator and a stand for the light, then you need a diffusion for it, you know what I mean? We had a bit of bounce for a little bit of eye light here and there, but for the most part we were shooting at dusk and dawn in Abu Dhabi. A bit of bounce was really all we needed to fill out the faces and fill out the eyes. Obviously there has to be some equipment because we’re making a film. You can’t just go out there with a pen and paper, but we tried to minimize that to allow the best footprint for the director and the cast.

Filmmaker: Walk me through your selection process when choosing lenses. You go back and forth between Panavision and Arri.

Fraser: I definitely have a predilection for certain types of glass. Generally, I like glass that has a certain softness or a roundness to it. It’s my personal opinion and there are many DPs who disagree with me—in fact, I’ve had debates with other DPs about this—but I feel like as we have gone from film to digital our resolution and sharpness has increased and I feel like our lenses were continuing to become sharper and sharper as well. I understand why that was happening when we were shooting film, because we needed really high resolving glass to counteract film that was going to be put out to a print, because you lose resolution every time you do a print from an internegative. I remember doing a test with a Red One years ago when they first came out, maybe 2006 or 2007. I used to own a set of Cooke S4s; I put them on the camera and was like, “Oh wow, they are super sharp.” Since then I’ve kind of been detuning my lenses. I’ve been trying to find the right balance of resolution and sharpness. They are two different things. There’s a certain roll-off to the focus on some lenses and it’s trying to enhance that roll-off and enhance that softness, yet still have an image that bites.

Filmmaker: It seems like almost every interview I do now, there’s some talk about tweaking or detuning the lenses. Did you do any of that individualizing for Dune?

Fraser: We had to. We used a set of Panavision Ultra Vista anamorphic lenses. The first time I used those lenses was on The Mandalorian. They were basically in the R&D stage when we tested them for Mandalorian and they were really good, but the way I had [Panavision] tune them up for Mandalorian was different than the way I had them tuned up for Dune. With Mandalorian, primarily we were shooting a guy with a chrome helmet, so automatically he looks metallic. We were trying to fight that from the beginning because he’s so sharp. So, the lenses were detuned a little more for Mandalorian. For Dune, we had to sharpen them up a little bit because we were shooting soft-featured human faces.

Filmmaker: You did a film-out process for Dune. So you output to a negative that you then have to develop, then you re-scan? Is that basically the process?

Fraser: That’s right. It used to be that you acquired on film, then scanned it and worked on it digitally. Now, when you shoot digitally as well, you remove any film element from the process, which a lot of filmmakers are rejoicing about because a lot of filmmakers can’t stand the problems of film. They don’t like the fact that they have to deal with the scratches and dust and grain. But then there are other filmmakers who are lamenting it and who love the organic nature of film. They love the scratches and the dust and the grain. For them, that’s what filmmaking is. I have had a foot in both camps. I understood why filmmakers loved shooting digital, but I also understood why filmmakers love shooting film. As a DP I’m sort of agnostic in the sense that if a director says, “I have to shoot film,” which many a director has, I don’t go, “Ah, dude, you can’t, really.” I’m agnostic. My job is such that I have to be. What I found with this [film-out] process is that it allowed me to have a clear vision of something that should look more organic than digital, but less organic than film.

Filmmaker: At this point if you’re going to shoot film, you don’t have that many choices in terms of stock. Do you have more choices when you’re doing this film-out process?

Fraser: You have many more choices. You have internegative stock, but also acquiring stock that you would use in the camera. You can also use interpositive stock. It allows more options for film stock, but also allows more options for how you deal with that film stock. Our film-out was to a 35mm piece of negative, but you also have the choice to not film-out to the entire size of that negative. So, you could film-out at 25mm because that’s how much grain you like for a particular project. Or maybe there are some scenes that you film-out at 35mm and there are some other scenes that you do at 16mm to create a point of difference. We’re getting our choices back. We’ve had our choices slowly reduced over the years and we’re getting them back, which I feel like is a really good thing.

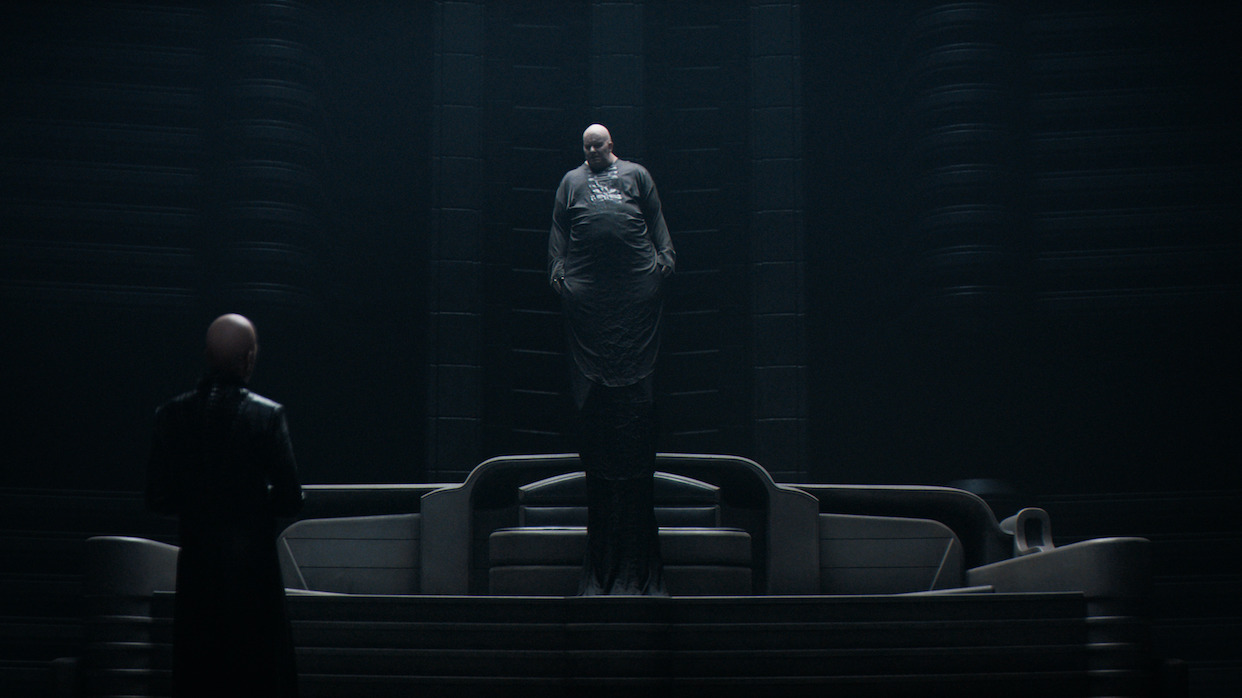

Filmmaker: Let’s finish up by talking about my favorite scene in the film—the raid on the Fremen ecological research facility. There’s a gigantic room in this “Nexus” structure with a huge concrete pillar in the center. At the top there’s an opening that lets in sunlight, casting this hard, wagon wheel-shaped shadow on the sandy floor below. How did you shoot that scene? You could never get artificial light on the stage to look that good.

Fraser: You’re a thousand percent right. You could not light that on stage. It would be literally impossible to light with multiple light sources and a single source would need to be 1,000 feet high. We went around in circles about that location for a number of months. We kept saying, “Well, it can’t be on stage.” Well, where can it be then? On the backlot? Well, how do you create that on the backlot? How do you darken an entire area of the backlot yet still create this gobo pattern?

At Origo Studios, there’s a fantastic design they’ve got where they’ve built into the walls of the outdoor stages the ability to put up speed rail and basically build a structure. So our riggers had this great system where they had pieces of fabric that they could [stretch across the top of the outdoor stage in this wagon wheel pattern]. They could pull the fabric in and out because you couldn’t leave the material up for a long period or it could rip. So, to shoot that scene we had to find a time where the wind wasn’t going to rip the fabric and it was going to be sunny. [To get those shadows right] we could only shoot for a 45-minute window if the sun was out. So it took very careful coordination between my assistant (who had done a light study), the 1st AD (who was scheduling) and [production designer] Patrice Vermette. If we had even an ounce of rain overnight we couldn’t shoot either because the sand wouldn’t look right. It was a very, very fine needle that we had to thread, but it was exciting. Visually, it’s one of my favorite sections as well.