Back to selection

Back to selection

“Do Younger Israelis Care at All About This History?”: Alon Schwarz on His Sundance-Debuting Doc Tantura

Tantura

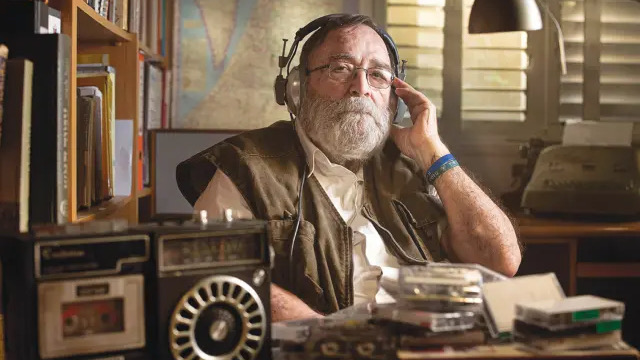

Tantura Alon Schwarz’s Tantura takes its title from a particular Palestinian village that was depopulated – by any means necessary, including through a still-contested massacre of civilians – during Israel’s 1948 War of Independence (aka “Al Nakba,” the Catastrophe, if you hail from the occupied side). Yet the doc is less a history lesson than a deep-dive investigation into the stories a nation chooses to tell about itself. Schwarz’s (Aida’s Secrets) own story began when he got access to over 100 hours of shockingly candid audiotaped interviews that the (government and academia-silenced) researcher Teddy Katz conducted decades ago with former soldiers of the Alexandroni Brigade (as well as with Palestinian witnesses to their potential war crimes in Tantura). Schwarz then continued down a rabbit hole that includes his own contemporary on-camera interviews with the now-frail Katz, and with many of these last remaining soldiers as they listen back to their unguarded testimonies and subsequently come to terms, dismiss, or even laugh off chilling admissions that this generation of Holocaust survivors would, rather ironically, now prefer to forever forget.

Prior to the film’s January 20th world premiere in the World Cinema Documentary Competition section of this year’s online Sundance, Filmmaker caught up with the director (and brother of longtime Sundance vet Shaul Schwarz) to learn all about his country’s My Lai-reminiscent incident, and whether the untwisting of truth could ever lead to actual reconciliation.

Filmmaker: So this film, which started out centered on Israeli activists fighting to end the occupation, took a completely different turn once you gained access to Teddy Katz’s treasure trove of audiotaped interviews with former soldiers of the Alexandroni Brigade. You basically spent hours “listening between the lines” of their accounts, so to speak, almost like breaking a code. Which is a fascinating story of detective work, but not necessarily a visual one. What made you think this material could form the basis for a movie?

Schwarz: I felt it was going to be an amazing story from the moment I went out of Teddy’s house for the first time with those tapes in my hands. Listening to them made my heart race — we are speaking about over 100 hours of interviews. The hard part was to decide what to leave out. It was a challenge as there is so much more there.

When I got access through research to some of the still-living veterans, it was clear that if I got a chance to have them listen to the tapes and look at the pictures and react it could be very strong visually as well. And that is what has happened.

Filmmaker: Your brother Shaul (who I’ve been following – and interviewing – since 2013’s Narco Cultura) is a writer and producer on this film, and he also worked on your last doc Aida’s Secrets. That said, he chooses to shoot almost exclusively internationally, while you seem more focused on subjects pertaining to your own country. I actually felt both angles in Tantura – a specifically Israeli story that nevertheless echoes America’s genocidal history (i.e., the Indian Removal Act) and even, most ironically, Nazi Germany’s policy of expropriation and extermination. So how do these “closeup” and “wide lens” POVs intertwine in terms of your working relationship?

Schwarz: Even though my future plans will probably soon take me to do international stories based outside of Israel, I do currently live in Israel, and I have a deep curiosity to tell its stories. My curiosity especially takes me to historical stories that evolved into myths that deeply affect our daily life without us as a society being aware of it. I also have an attraction to speaking with old people and learning about the secrets they hold. My first film, Aida’s Secrets, also involved a huge research project and old people exposing secrets. It was set at a time period just a few years before my current film.

Shaul and I work together on some of our projects – I was involved in Narco Cultura‘s story-building, and Shaul has been involved in both of my films. We work well together, and like all partners and brothers, we sometimes have disagreements which at the end usually make our work more fruitful. But our overall strategy of working together is to choose for each project who leads and then if we don’t agree on a certain cut or scene we know who is to make that last decision.

Although it’s okay to compare them as a mental exercise, I don’t think Israel’s founding story is exactly similar to America’s story or Germany’s story – at least not in the scale, the relative number of civilian victims, and of course, not in the systematic state-led extermination ideology of genocide defined as policy and goal. But nevertheless, Israel’s founding story has been told and sugar-coated by the winners. In reality, it involved the depopulation of hundreds of villages and several towns, and as part of these events many war crimes were committed. And in most cases they were silenced then, and are still silenced today.

Filmmaker: It strikes me that as an Israeli (and former soldier) you can get unguarded access to these veterans in the same way that a lot of white guys can get white supremacists to let down their guard. There’s a level of tribal trust there, warranted or not. Did you use this to your advantage – or were they just truly convinced of their own moral superiority, and thus unapologetically forthright? Why do you think so many were so open with you?

Schwarz: I’m indeed one of them – an Israeli, a Zionist, and a nice guy. They are the creme de la creme of Israeli society. None of them is really proud of what happened in Tantura probably. Some feel guilty, some feel morally superior – each is different.

I believe that as the years passed they told themselves the story in a way that made it easier for them to remember it and to live with it. That’s very natural. Their narrative, often, is one that says there was no choice – that had Israel lost the war there would have been extermination camps of the German model set up by the Arabs to finish off the Jews in Israel. That’s not an easy thing to argue with. My point is not to judge history retroactively, but rather bring to awareness the true historic story, which has been hidden, and see how if we look at it differently today it may help us bridge some of the gaps with our Palestinian neighbors.

Filmmaker: For me the most memorably chilling characters in the doc were the soldiers (and one academic) who not only shrugged off but even laughed off the Tantura massacre. They’re smiling and almost jovial in their interviews about this ethnic cleansing, which left me not only horrified but completely perplexed. Is this some sort of defense mechanism? Are they sociopaths? Did you gain any insight into such an inexplicable reaction?

Schwarz: I don’t think any of them are sociopaths. They are old people from my grandparents’ generation who were born to a historical context that meant they needed to survive not only as individuals but also as a group. It’s out of that embracement that you see these reactions. They are all normal people who, when they were 17 or 18 year-old kids, fought a terrible survival war in which many war crimes were committed. And hidden.

Filmmaker: There seems to be a lot more on-camera silence-breaking over the past decade in Israel – from Dror Moreh’s 2012 doc The Gatekeepers to Avi Mograbi’s brilliant The First 54 Years – An Abbreviated Manual for Military Occupation just last year. (Though perhaps historically taboo subjects are just now reaching international audiences.) Is there actually more societal openness today, maybe now that the founding generation is passing on? Or did you reach out to a lot of folks that still refuse to talk?

Schwarz: I think the films you mentioned are part of a larger trend that indeed brings another narrative to the table, one that was academically brought to the world of intellectuals and scholars by The New Historians in the ’80s but then forgotten. These silenced narratives now come to the masses by way of cinematic storytelling.

In addition to those films you mention there is also Blue Box by Michal Weits, which is in my eyes a super important, eye-opening film (that unfortunately has not yet been seen much outside of Israel) as it lays out the systematic activity of cleanup of people from the land. So yes, it’s a new trend by filmmakers as well as writers (and younger historians like Adam Raz, for example) who want to tell Israelis another story. And for the first time there is in Israel an ability to not fight these stories and to let them be told out loud.

The question is, do younger Israelis care at all about this history? And to that I am not sure I have a good or happy answer. But it’s important to tell, and slowly change our collective perception of our idyllic history. And most importantly we must acknowledge this as a country, in order to create a base for dialogue and actually see the people on the other side as equal humans and future partners.