Back to selection

Back to selection

Rediscovering the NBA’s First Female Player: Ben Proudfoot on The Queen of Basketball

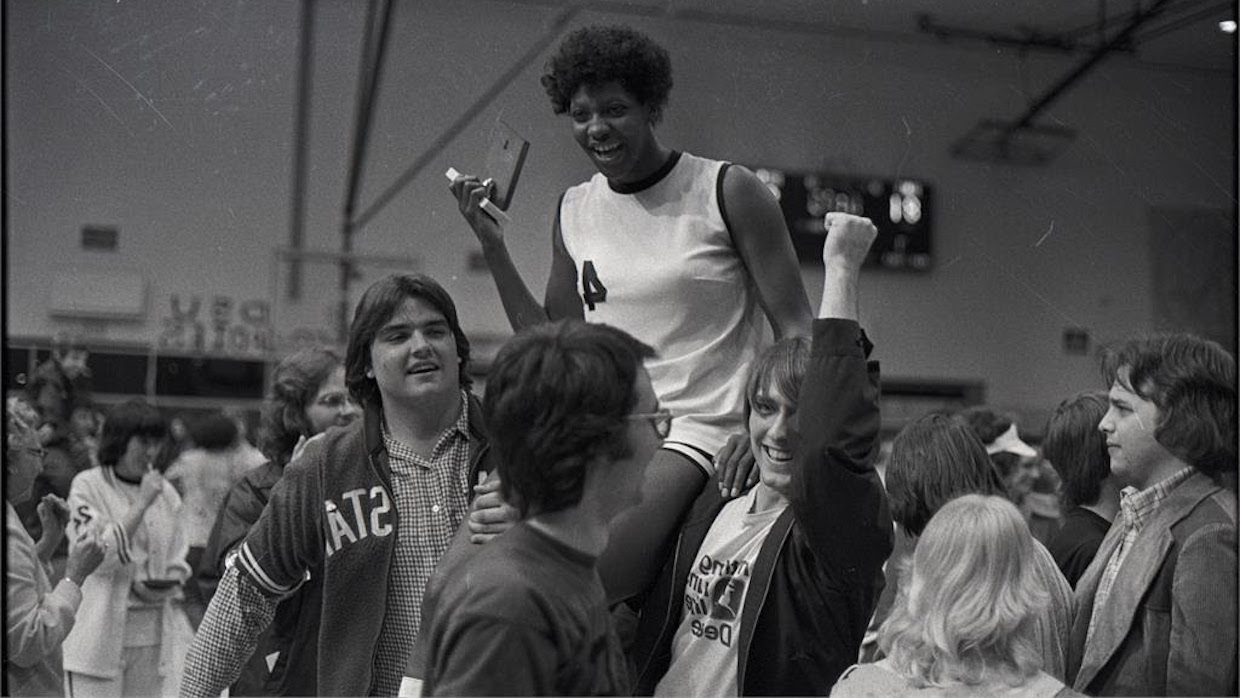

Lusia “Lucy” Harris (courtesy of New York Times Op-Docs/Breakwater Films)

Lusia “Lucy” Harris (courtesy of New York Times Op-Docs/Breakwater Films) More than just the answer to an obscure trivia question, Delta State University’s Lusia “Lucy” Harris was one of the most dominant basketball players of her era, eventually becoming the first woman drafted into the National Basketball Association (NBA) in 1977. Her collegiate and amateur accomplishments were numerous, including three national championships and a 51-game winning streak while being the only woman of color on the Delta State Lady Statesmen women’s basketball team. (Her home games were played in an arena that, to this day, remains named after Walter Sillers, Jr., a prominent white nationalist.)

Director Ben Proudfoot’s documentary short A Concerto is a Conversation was nominated for an Academy Award last year. Now, just over the age of thirty, Proudfoot has again been nominated for The Queen of Basketball, his profile of Harris’s personal life and hardwood career. An inclusion in The New York Times’ Op-Docs anthology “Almost Famous,” Proudfoot’s film literally puts Harris front and center as she tells her story in her own words. Spirited and humorous, Harris’s storytelling beautifully works in tandem with Proudfoot’s filmmaking, walking the fine line between archival doc and first-person profile.

While the Women’s National Basketball Association (WNBA) is increasingly successful, its players experience significant wage disparities compared to their male counterparts (so much so that star players spend offseasons playing overseas in dangerous conditions). The time feels right for Harris’s accomplishments to be more widely celebrated. Premiering at last year’s Tribeca Festival, where Harris was on hand to see audiences celebrate her life, the film continues to find success thanks to high profile executive producers and end-of-year award citations. The week of the film’s receiving an Oscar nomination, I spoke with Proudfoot over Zoom about his in-demand company, Breakwater Studios, how he initially heard of Harris and his use of a filming technique made famous by Errol Morris.

Filmmaker: As you’re the founder and CEO of Breakwater Studios, I wanted to ask about the origins of the company and how it’s grown to become focused on producing nonfiction short films for a wide audience.

Proudfoot: This month [February 2022] actually marks the 10th anniversary of the company, and the origin story is pretty simple. I came to Los Angeles from Halifax, Nova Scotia as an undeclared student attending USC [University of Southern California], having been rejected by [USC’s] film school. I spent a lot of my time in the film studies program, simultaneously learning about the old studio model and getting my first experience of what the studio system was like today. I was nonetheless crestfallen that the studio system wasn’t the “creative campus environment” I assumed it would be. The idea of each creative department gathering together in one place to collaborate and have lunch together didn’t seem like it was happening there. Rather than an artists co-op, it felt like a more itinerant, movie-themed WeWork.

Gearing up to graduate, I decided I could either change industries, try to work at one of these pre-existing film companies or maybe even start my own company in the image of what I had expected to find when I arrived in L.A. Breakwater was founded with the idea of having all of the creative departments gathered under one roof. I had no plans to make the company short-documentary driven, nor had I ever done anything in partnership with brands—yet these have become the two halves of our business model. Through a school project/short documentary, Ink & Paper, that link, that synapses fire, became apparent. I felt I could recognize a great story and essentially make it [into a documentary] with my own limited resources, release it on the internet and, if it was really good, 100,000 people might watch it. I didn’t have to ask anyone’s permission in the process. I didn’t have to go through the process of pitching or fundraising. I could just go make it.

Ink & Paper was made in 2011. While it opened up a whole world for me, as time went on, I realized that the short-doc format was somewhat looked down upon, as if it were the student format—a means to an end to obtain a coveted series or feature directing gig. The hierarchy of prestige and importance was clear, with feature films at the top of the food chain and short-documentaries squarely at the bottom. But that doesn’t make sense! Visitors don’t go to the Louvre in Paris to see the small paintings on the first floor for free, then work their way up to the large paintings by the “important artists” on the top floor that they have to pay for. There’s no real industry centered around short documentaries and I didn’t understand why.

The short doc format is the most exciting corner of cinema, certainly the most accessible in terms of filmmaking and the different talent available. It allows filmmakers to shine a spotlight and give voice to stories ignored by the industry, to do so with tremendous style and cinematic panache, and potentially reach an audience of millions over the internet, on YouTube or wherever else. That could be considered cinema! It’s not videography or simply a YouTube video, it’s cinema. I basically put all my time and chips into the form and have been making short documentaries for 10 years now

Filmmaker: You’ve made several popular short-docs for The New York Times’s Op-Docs anthology. How did that partnership begin?

Proudfoot: Our business model (i.e. how we make money) is making films directly with brands. The money from that business model allows us to then invest in original content, original short-form documentaries. We had made a short-doc, The King of Fish and Chips, about a fish-and-chips mogul, Haddon Salt, who sold his business to Kentucky Fried Chicken in the 1960s.

Filmmaker: This short became a part of the Almost Famous anthology?

Proudfoot: It did. They really liked the film after viewing it in Montana at the Big Sky Documentary Film Festival and decided to license it [as an Op-Doc]. That’s how the partnership between Breakwater and The New York Times began, and it kicked off a conversation where we came to them and said, “We would really like to tell more of these types of stories. We pitched an nonfiction anthology called Almost Famous that would [draw light on] people who, if history had gone a little differently, would’ve been household names today. Lindsay Crouse, the commissioning producer for the [Op-Docs] series at The New York Times, liked the idea and added the layer of focusing on stories where society was the deciding block, where a [subject] (due to being a woman or Black or another specific personal element) was overlooked by society. It felt like a really interesting way to explore these stories, so that’s what we did, focusing on an anthology of short documentaries where luck or timing also played a factor.

This process allowed us to strike up a solid working relationship with The New York Times, whom we then made A Concerto is a Conversation with in 2020. We also made a series of short films (titled Cause of Life) at the end of 2020 centered around victims of the coronavirus. The New York Times has served as a great platform for short documentaries, as people visit the site to learn something new and expand their world. Short documentaries fit well into that mindset.

Filmmaker: Since A Concerto is a Conversation came from a very personal place (featuring co-director Kris Bowers’s grandfather, Horace Bowers Sr., as its main subject), I was curious how your relationship with The New York Times has expanded beyond the Almost Famous anthology. Have there been moments where you’ve provided your own pitches for non-anthology-based stories that don’t fit into a pre-existing New York Times series?

Proudfoot: A Concerto is a Conversation is an example of that, a story that was outside of the anthologies and themes we were previously exploring for them. One of the reasons we get along with the Times is due to Breakwater being a company that’s interested in original reporting, in finding a story no one else has really dug into before. Rather than going through the process of adapting a preexisting written article into a documentary (which, I think, is probably what people expect these films to be), we see ourselves as both the journalistic and filmmaking part of the equation. Any time the films we’re interested in making align with what the Op-Docs team is interested in producing, the partnership seems to work really well.

Filmmaker: How did Lusia “Lucy” Harris’s story first come to your attention? Did you come across it by stumbling upon the story of a woman being drafted into the NBA?

Proudfoot: Well, that certainly piques one’s interest! Back in July of 2020, when we had already released four films in the Almost Famous anthology, I realized I was most interested in this sort of purposeful storytelling, of using the short-form to close the gap between how significant a person was versus how many people knew of them. My colleague, Haley Watson, who’s a cinematographer and director, very simply said, “You should look up Lucy Harris.” Haley had done some research on Lucy. I think I had only landed on her Wikipedia page which, while not very long, featured a superlative list of her accomplishments, including three national championships, being the first and only woman officially drafted into the NBA, being the first woman to score a basket in Olympic history, being the first woman of color enshrined into the Basketball Hall of Fame. All singular accomplishments—but from the late 1970s onward, there was almost no information about her. There was a lot of speculation about why Lucy had said no to the NBA, i.e. was she pregnant? There were many unanswered questions.

It seemed as though Lucy was still alive, so I called Lindsay, who also happens to be a thought leader in the coverage of women’s sports, and told her Lucy’s story. Lindsay was the first person to say this to me, which I’ve heard hundreds of times since: “Why don’t I know this story? Why don’t I know the name ‘Lucy Harris?’” When you get that kind of reaction of anger about not knowing someone’s story, you’ve found a story that ought to be told. That’s great motivation to go make that film.

Filmmaker: Was Lucy still living in Mississippi at the time? Did you reach out to her or go through one of her children?

Proudfoot: Lucy was living in Greenwood, a small town in Mississippi, and I reached out to a few people in hopes of finding her. I was searching for possible phone numbers, made some calls, eventually got through to Lucy and explained who I was and that I would love to come to Mississippi and help her tell her story. She responded, “Come on over.” Lucy was very, very casual, and I said, “OK, maybe we can schedule it in advance?” She responded, “I’m retired. You can come anytime.” Lucy was very soft-spoken and that’s what was so uncanny about her. Here you had arguably the most accomplished female athlete of the 20th century, certainly the most dominant player for an extended period of time, who was also completely unassuming—disarming, soft-spoken, hospitable, always focused on you. She was living in a normal neighborhood in Mississippi and anyone who came aboard this project joined the galvanized march to correct the historical oversight and make Lucy Harris famous, as she should be.

Filmmaker: The film also makes use of the Interrotron, a popular camera device made famous by another nonfiction filmmaker, Errol Morris. For your previous film, A Concerto is a Conversation, you employed two Interrotrons, I believe.

Proudfoot: Yeah, we used two on that film [one fixed on Kris Bowers and the other on his grandfather, Horace Bowers].

Filmmaker: How did the Interrotron originally find its way into your films? How does it help achieve your intended effect?

Proudfoot: As soon as I discovered Errol Morris’s films, I wanted to know how that particular effect was done. I was a magician as a teenager and there was an illusionary element to the way Morris [shot interviews]. There’s a famous magic trick, Pepper’s Ghost, that uses a similar principle, you can see an example when you’re peeking into the ghosts dancing in the ballroom at The Haunted Mansion at Disneyland. It’s a huge piece of glass at a 45 degree angle. As soon as I learned about Morris’s use of the Interrotron, I took to building one myself, and while that took some doing, I’ve since been able to make several documentaries with it.

My goal is to focus on the storyteller telling their story to an audience, to a viewer, rather than having them tell the story to me off-camera, or having me tell their story for them. As a nonfiction filmmaker, I want to advocate for the storyteller’s right to tell their own story. The Interrotron is, then, the perfect tool: the audience and the storyteller are directly aligned at eye level and I’m invisible, at least most of the time.

In terms of comfortability [for the subject/interviewee], the Interrotron is a great tool to ease people up and get them comfortable, as if they’re partaking in a conversation. You and I, at this moment on Zoom, aren’t really looking at each other, right? You’re looking at a computer screen and I’m looking at a computer screen, but it’s still easy for us to connect with one another and engage in a slight suspension of disbelief. There’s nothing I really do to help them feel comfortable, other than set up the Interrotron and being vulnerable myself and honest about why I’m there. I tell them my intentions, lay out what I plan to do, then invest the time to hear their story. I’m not trying to apply my idea of their story onto them; I want to get it directly from them.

Filmmaker: When you’re dealing with a story so dependent on archival footage, what comes first: your archival research or the interview with your subject?

Proudfoot: Normally I comb through the archives first to see what’s available, hoping that might clue me into certain parts of the story that were visually covered throughout the person’s life that we can then discuss in person. I’ll then ask specific questions related to the footage, like “I noticed that you were injured in the third quarter of that one game—tell me more about that,” etc. But, in the case of The Queen of Basketball, we went into the interview having exhausted everything we could without finding much footage. We had maybe two dozen photos of Lucy and that was it. We couldn’t find any footage of her playing days and I didn’t understand why. She was so preeminent at her craft, and this was only back in the 1970s, not 1910 or 1920. You would think her playing career would’ve been pretty well covered. Nonetheless, I went into the interview somewhat empty-handed in terms of archival footage.

We then had an enormous breakthrough. We visited the Delta State University archives to borrow one reel of film, and while I was signing the rental form, I asked one more time, “Are you sure this is all you have of Lucy playing?” And the archivist that day responded, “Oh no, we have a lot more.” I was led to this room that resembled a warehouse in the Indiana Jones movies and in the back corner there were shelves and shelves of 16 millimeter film, tens of thousands of feet of it, as well as boxes of negatives, U-matic tape, newspaper clippings and memorabilia.

We scanned everything we could in the limited amount of time we had. The archivist even called her mother and everybody came together to work on this, scanning newspaper clippings and other printed materials. We then brought all of the footage to Washington, D.C. to be scanned in 2K. That was a whole summer project for us, scanning thousands of negatives and digitizing all of Lucy’s legacy. It was miraculous to suddenly see the stories Lucy had been telling us all of a sudden flickering to life with what we discovered in the archive. All of that stuff had previously been undigitized, uncataloged and unsearchable.

Filmmaker: It’s amazing when Lucy recalls the nuns from Immaculata College who would bang on buckets to cheer on their school. Like, how would you even find that footage? You can’t search “keyword: nuns” when looking through old footage by hand.

Proudfoot: That’s a great example. As Lucy is telling us this story, saying that the nuns were “beating on buckets,” I’m listening to her while not being entirely sure of what she’s talking about. I thought maybe “beating on buckets” was a Mississippi idiom I just didn’t understand. I was like, “OK, let’s move on.” Later, once we were reviewing the old footage, sure enough we came across the nuns beating on buckets and making noise and attempting to distract the other team. There were endless examples like that, where Lucy would recall a story and then we’d find it in the archival material just as she described.

We also caught a number of lucky breaks. Kodak was, to their credit, a big sponsor of women’s basketball back in the 1970s and commissioned a number of very well-shot films featuring Lucy in beautiful 16mm, some in slow motion, and beautifully rendered. That was a dream come true for us, finding this footage that Lucy could attest to since, at the end of the day, you have to see it to believe it. When you see Lucy jogging up and down the court and scoring or being celebrated with a ticker tape parade, it’s like, “Wow, this actually happened.” That was a huge breakthrough for us, where the heavens opened up and we found that Kodak trove.

Filmmaker: When did you learn that Lucy was bipolar and struggling with mental illness? Was that something you brought up yourself or were you hoping she would?

Proudfoot: I had no idea about that part of Lucy’s life, no. She brought it up over the course of our interview. When someone brings up something personal and sensitive like that, the first question you ask is, “Are you sure you want me to include this in the film?” And Lucy was eager to, in part so that the film could erode the stigma around mental health. We talked about it at length in the interview, in vivid detail—her experience of dealing with bipolar disorder and how that affected her adult life. Of course, many of our own life-stories possess multiple facets, advancements, setbacks, unexpected obstacles and incongruencies, and it’s our job to make sure that each can be integrated and emulsified into a single storytelling experience that feels like an essence of their truth.

Filmmaker: How did Shaquille O’Neal come aboard the project as an executive producer?

Proudfoot: Our goal was simple: we wanted as many people as possible to know about Lucy Harris. Shaq saw the film and got in touch to ask how he could help. We told him our goal and he said, “Well, that’s now my goal, too.” Shaq has participated [in several post-screening Q&As] with us. Our whole team is galvanized [by] making Lucy Harris famous, making her story known, rectifying the oversight, bringing her story to light in as many corners of the country and around the world as we can. She’s someone who deserved the credit and an opportunity back then, and that’s why we’re [doing this]. Tragically, we lost Lucy unexpectedly in January [Harris died a few weeks shy of her 67th birthday in Mound Bayou, Mississippi], so while she may not be here to see us progress, her passing only increases our commitment to making sure that her legacy isn’t forgotten.

Filmmaker: You’ve spoken about having your films be accessible, non-paywalled and viewed by as many people as possible. They’re certainly very sharable, which is something different than “going viral.” I know a number of people who shared with me the Almost Famous episode about the casting of Anakin Skywalker for Star Wars Episode I: The Phantom Menace without ever seeking out who made the documentary or having the context that it was part of a larger anthology called Almost Famous. Has the availability of your films opened doors for you in different ways?

Proudfoot: Doing things this way certainly doesn’t make me a lot of money, nor does it optimize my net worth, but that’s not my goal. My goal is to enrich an audience, not myself, and that’s why I like The New York Times and YouTube. It’s why I like making short docs and hosting them on those platforms—people actually watch them. Imagine spending a year making a movie only for it to sit behind a paywall and nobody can see it. No amount of money can make me feel good about that. It’s 100% satisfying to have conceived of a story with a group, finance it ourselves, go out and make it, finish it ourselves, work with a platform like The New York Times to get it out to the public and, in the case of The Queen of Basketball, find someone aligned with the story like Shaq, who can amplify it and help bring the story to millions of people. What’s missing from that process? The only thing missing is money raining from the heavens down onto us. And I’m OK with that.

Filmmaker: That will come, that will come.

Proudfoot: Maybe. And if it does, we’ll just make more movies!