Back to selection

Back to selection

“Pretend Sonic Youth Composed the Score to Jaws“: Deakin and Geologist of Animal Collective on Scoring The Inspection

22 years after the release of their debut album, the Baltimore-bred quartet Animal Collective is as prolific as ever. Members Avey Tare (Dave Portner), Panda Bear (Noah Lennox), Deakin (Josh Dibb) and Geologist (Brian Weitz) released their 11th studio album this year—the delectably jammy Time Skiffs—to a wave of acclaim the band arguably hasn’t received since their indie-tronica staple Merriweather Post Pavilion in 2009. On the heels of Time Skiffs’ success, the band has already hit the studio to record their forthcoming release, rumored to hit shelves and streamers from the band’s longtime label Domino Records in 2023.

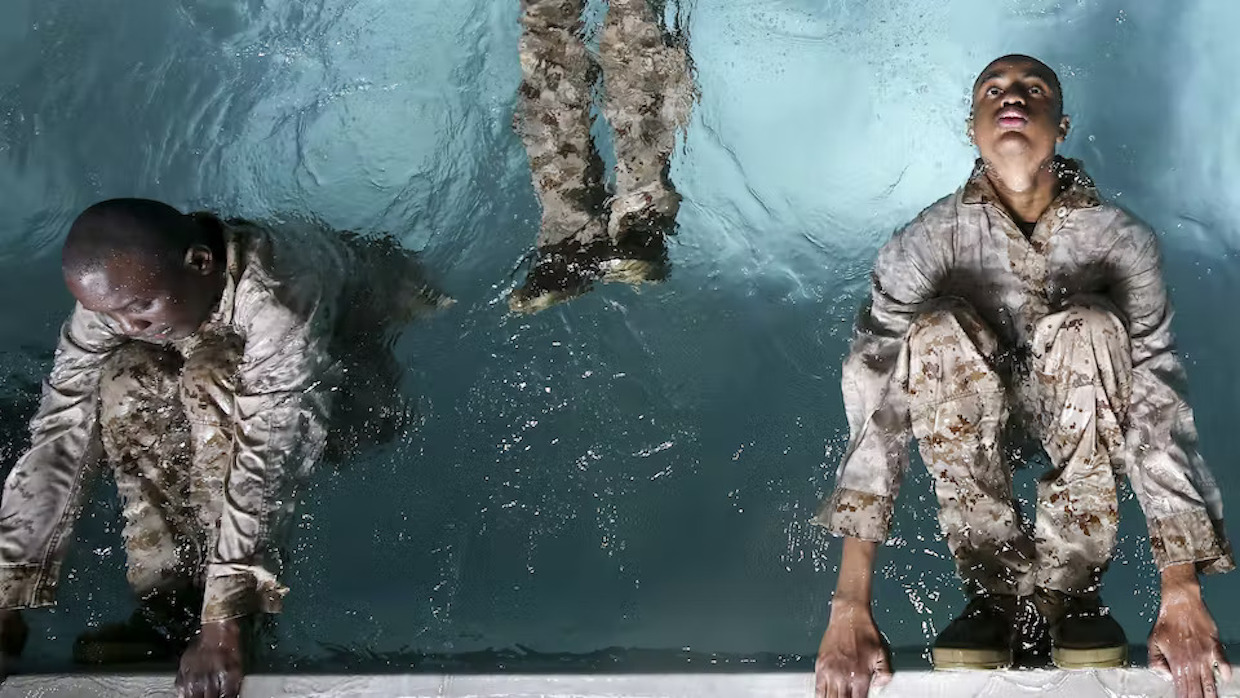

This year has also featured an (almost) entirely new venture from the band: composing the score for Elegance Bratton’s narrative debut The Inspection. Based on the writer-director’s own experiences as a gay Marines recruit during the mid-aughts, Bratton’s identity as a long-time indie head enmeshes itself in the film through the band’s very involvement. “I listen to [Animal Collective’s eighth studio album] Merriweather Post Pavilion twice a week, from beginning to end,” he told Erik Luers during a recent interview.

As novel as Animal Collective’s involvement was for Bratton, The Inspection is not the first cinematic collaboration the band has embarked on. In 2010, all four members teamed up with long-time collaborator and Antibirth filmmaker Danny Perez on ODDSAC, their first visual album. Utilizing elements of horror and avant-garde abstraction, the film is made up of 13 songs/vignettes of surrealist scenarios—bleeding houses, drum kits in river beds—often featuring the band members themselves. (The Panda Bear-penned “Screens” has made a regular appearance during the band’s recent Time Skiffs tour.) The band, sans Panda Bear, collaborated with Coral Morphologic on their subsequent filmic release in 2018, a “visual tone poem” dubbed Tangerine Reef . Most recently, Deakin and Geologist scored former 25 New Face Marnie Ellen Hertzler’s Crestone, a meditative doc that chronicles the weed growing exploits of SoundCloud rappers (who happen to be Hertzler’s high school friends) as they descend into squalor and apathy in the Colorado desert.

Deakin (Dibb) and Geologist (Weitz) spoke to Filmmaker via Zoom to discuss the intricacies of composing The Inspection‘s score alongside Avey Tare (Portner) and a less-involved Panda Bear (Lennox). During our conversation, the musicians touched upon navigating studio notes, how this film differed from their previous visual collaborations and teaming up with Indigo De Souza on the end credits song “Wish I Knew You.”

The Inspection hit theaters via A24 on November 18.

Filmmaker: Were you previously tuned into Elegance Bratton’s work or perhaps connected via the wider Baltimore artistic community?

Weitz: I think [the request] came from A24, actually. We were not familiar with Elegance. I think Josh knows some people that Elegance knows as well, so maybe Pier Kids had come across your radar?

Dibb: We weren’t familiar with Elegance’s work, but our friend Marnie Ellen Hertzler—who directed Crestone, the last [film] we worked on—had met and/or knew of Elegance. He was looking for someone to score the film, and he’s a fan of ours. We ended up connecting with him, and the reason why he wanted us involved had a lot to do with the influence that the band had on him, especially in the 2000s. I don’t think he would’ve even consciously thought of us as people to ask, but talking to Marnie and knowing that we had scored her film made him realize that we were [an option]. That was the initial connection, then the request came through A24.

Filmmaker: As a band, you’ve worked on various visual albums and film projects. You collaborated with Danny Perez on ODDSAC, made Tangerine Reef with Coral Morphologic and, as you said, both composed the score for Marnie Ellen Hertzler’s Crestone. How did your work on these projects influence your artistic process with The Inspection, and how did collaborating with Elegance compare or differ to working with these other artists?

Dibb: The relationship between music and [visuals] is something that we’ve been interested in since we were kids. Brian and Dave [Portner, Avey Tare] had a very formative experience watching The Shining, and that movie has influenced all of us. We each had our own experiences in realizing that the connection between visual and audio is such an important thing. That’s always had a role to play in our music, in general. It’s very common that we talk about what we’re trying to do in visual terms. We’ll say something like, “This needs to feel more like this color,” or “I want this to feel like it’s a stormy night on a mountain.” Talking about what something should sound like [through visuals] is ingrained in how we think about music.

That’s a large part of how the Danny Perez collaboration happened. He’s an old friend and we’ve known him for a long time, but we wanted to meld those two worlds. Having not, at that point, ever been asked to do a film score, we basically wanted to create a situation where we could start to mess around with that directly in our own way. That process allowed us to both write songs and, in an almost music video-like way, collaborate with Danny visually. Everything that exists in that movie also gave us the template for everything we’ve done since. There’s a section that we would always call “Urban Creme” in ODDSAC, which is just a kind of static imagery, which I feel is very similar to how we approached Tangerine Reef, for example.

Meanwhile, something like [“Fried Camp,”] the campfire scene—eating marshmallows and stuff—would maybe be a bit closer to some of the work we did on The Inspection. I think that way of relating to imagery and music has just been huge for us for a long time. Each of those projects feels linked, while also feeling like very different lanes of that relationship.

Weitz: The thing that’s different about The Inspection, at least speaking for myself, is that with the three other projects that Josh spoke to, the visuals that were on screen—landscapes, scenarios and aesthetics—were all things I really related to. Obviously, with Tangerine Reef and ODDSAC, we were part of the genesis of those projects. We knew what was happening and had a relationship with those filmmakers. Crestone was the first time where [a filmmaker] had asked Josh to work on it, then Josh asked if I might be interested. Josh said something about SoundCloud rappers, and I just didn’t know. But then when Marnie showed us footage, it was all desert. I used to live in the desert, so I was like, “I know this.” There are sounds in my head that I’ve never been able to get out from when I lived there.

The Inspection was the first time we were shown a script and footage where I felt like, “I have no relation to this whatsoever.” Both in terms of a lived experience that was in the script or being at bootcamp or anything remotely military-related. High school soccer is maybe the closest thing I’ve experienced, you know? So it was a huge challenge to say, “Yes, we’ll give this a shot and connect with Elegance.” We hit it off pretty quickly, but to actually try and support a world emotionally and tonally that we had no connection to was a big challenge. This was the first time we ever tried anything like that. I think we got there in the end, but it was definitely an unfamiliar situation.

Filmmaker: Yeah, I noticed that The Inspection feels devoid of a broader environmental element. Your work has long been connected to landscapes and the natural world, but much of this film takes place in a world of sterile conformity; the rugged terrain they traverse during boot camp drills is manicured to mimic the elements they might endure during battle. How did you evoke this setting through the score, and did this disconnect from the natural world pose any challenge artistically?

Weitz: To me, it was huge. I remember getting notes like, “This should feel like supportive dread.” We’re familiar with working with emotion, but so much of this specifically happened to Elegance. He would tell us his inner monologue emotional state, and we had to find a way to express that. At the beginning of this process, I would just throw my hands up and be like, “I don’t know, man. I’ve never been in that scenario.” It just took a lot of trial and error for him to finally say, “Yes, that’s what I was feeling and this [song] expresses it.” Sometimes it didn’t work, and it took a lot of passes, which we’re not used to. Working in Animal Collective, we have a language that goes back 30 years. I mean, in the band people will often say, “No, that doesn’t work for me,” or, “That’s not what I envision there.” But we know how to move past those moments. When it came to things with Danny, Coral Morphologic or Marnie, we were already on such similar pages. So again, this was a huge challenge.

Dibb: I work in a very instinctual way, so being in an emotional world is how I relate to music, anyway. I almost feel like I was working less with notes, and more so continuing to [capture] the emotional landscape as opposed to the natural. What became the new challenge for this project were things like, “OK, well that’s cool, but can we intimate military cadence and not hit it on the nose?” Just bringing in pallets wouldn’t be our normal way of doing things. Trying to bring that emotion to a scene with, you know, distorted guitars—which is not something that we’ve spent a lot of time with over the course of 30 years.

Filmmaker: Expanding on that, I’m curious as to how you took notes from the director and adapted the sonic landscape of the film to each narrative beat. For example, I notice that on the soundtrack there’s a “Movie Edit” of the track “Shower Fantasy” alongside an “Original Mix.” How did the feedback you received guide you through tailoring the score to the film?

Weitz: A lot of those notes came from A24. Elegance kind of prepped us for that. There are three parties that are always going to have to be happy with the score: the band, Elegance himself and the studio. There were times where two parties would be on the same page, and one wouldn’t. I don’t mean to make it sound like it was always us and Elegance versus the studio, because it was not like that at all. Sometimes, we as Animal Collective were out on an island feeling like we had to advocate for something. Working within the band, we don’t normally take notes from anybody except each other. Opening ourselves up to that and realizing that it can push us into a better place was helpful.

That specific scene was actually one of the first things that was worked on almost a year ago. It came out of a lot of discussions we had with Elegance, as well as a playlist he sent us. It was also based on the original script we saw, which was not what was eventually shot. We saw a script that had a lot more from Elegance’s life in New York City, when he was homeless and a part of the ballroom scene. So, in our early discussions, he kept playing us the song where Sonic Youth covers Madonna, “Into the Groove(y)” from [Sonic Youth side project] Ciccone Youth. That was a huge inspiration—for him, for the score. He kept referencing that: “I want the score, even in the military scenes, to feel like this. New York punk, but also Madonna. Gay and danceable.” So, we started the score very much in that direction.

As the studio got involved and the edit took shape, [it became clear that the film] was only going to take place at bootcamp. Without the context of that New York world, [the score would now] actually seem really incongruous, because we haven’t established that tone visually or narratively anywhere else. Again, we didn’t know that initially, because the editing process and reshoots weren’t done. So that shower song was written when we thought, “We’re going to be playing against type for a military film and bootcamp scenes.” We thought there may be more of these surreal moments, where you’re in French’s inner head and he’s flashing back to this New York life and contrasting that with his surroundings in the bootcamp. Once there was less of that in the movie, we had to pull back. I think the music for the shower scene in the original mix maybe read a little too song-y compared to the rest of the score. But we also really liked it, and since it informed so much of the score from the beginning, we were attached to it. The “Movie Edit” that made it on the soundtrack was [shaped] by the music editor with our input, but it just felt like it was a piece that deserves both points of view: the original version that we started scoring, then what we ended up doing. We can get precious about things. So I think all of us felt like, “Hey, let’s include the original mix, because it’s something very specific.”

Dibb: Missy Cohen, who was the music editor on this film, deserves a tremendous amount of credit for wrangling A24, Elegance and us to focus the direction of things. There were a lot of continuous notes going from our own interests, to what Elegance really wanted, to A24 having notes and none of us ever meeting anybody at A24. Missy really did an incredible job of helping us see what was really working in the film, focusing it, and getting Elegance to understand what he was ultimately going for. [She saw] what our strengths were and advocated against A24 when she felt like they had a note that was maybe valid, but also [partially] just them not seeing what the core aim was with Elegance’s vision.

I think that’s an aspect of score work that we hadn’t really come up against until we worked on this film. Seeing how she handled that was just an incredible learning opportunity. We learned how to approach a score and understand that you’re not just working with your own instincts—you’re working with the director’s vision, you’re working with the studio’s, and they’re all legitimate voices. Finding a way to sift through that and come out with something cohesive, she really provided a masterclass in helping us understand that process.

Weitz: I think we needed to be told both by Missy and A24, “When your score comes into the movie, you’re not the focal point. There’s still narrative, acting and dialogue happening. You can’t take over.” I think that’s another difference between something like ODDSAC, Tangerine Reef and even Crestone, to a certain extent. Tangerine Reef and ODDSAC have music the whole time, but for Crestone, we knew that when our score came in, it was almost going to be the focal point in that moment. So, we had to get out of that mindset. With the shower scene, we approached it too much like a music video, which was the note we got back: “It feels too much like it’s shifted into a music video for this song.” The score was asserting itself too much.

Dibb: At the same time, that’s what Elegance wanted. It was like having two different parents [telling you what to do]. Elegance was like, “I want this to be a surreal fantasy moment of being in the club.” The studio was like, “Where did this come from? Suddenly we’re in a music video.” Again, that’s where Missy played a really great role in finding a way to honor what Elegance wanted while also balancing what A24 was comfortable with.

Filmmaker: As a long-time fan of the band, it would have been kind of a flex to have a de facto Animal Collective music video smack dab in the middle of his film. I’m sure that wouldn’t have been against his broader interests.

Weitz: No, but I think it would’ve made more sense had the movie visited more of his pre-boot camp life than it does. It would’ve helped the surrealist aspect play better. Without that, it did feel like a strange moment [laughs], especially to people who are not familiar with Animal Collective or Elegance’s sensibilities.

Filmmaker: You alluded to Elegance sending over a playlist and some of your own inspirations when it comes to melding visuals with music, but I’m curious if you consulted any specific scores or musical references when you first started developing this project. I know Elegance previously told us that his idea for the score was very much rooted in spiritual and religious music, such as “Muslim prayer concepts and Catholic choral orchestrations.” What other touchstones helped you evoke that?

Weitz: None of that stuff was really in the initial playlist he sent us. He referenced certain film scores—two that I remember the most were Bram Stoker’s Dracula and Jaws for the pool scene. We would get a note like, “Pretend Sonic Youth composed the score to Jaws.” When it came to the religious stuff, we weren’t sure if that was going to be for the church scenes, and we weren’t even sure if we were going to be composing that or not.

Dibb: I can’t remember the earliest moments of hearing him make some of those references. Some of them may go back to before we really started working, but like Brian said, it wasn’t a heavy element of the playlist or the notes he was sending. At a certain point, he did start talking about a call to prayer. There are three main sections of the film, and there’s a sort of tag moment that repeats a few times. The almost gospel-y stuff wasn’t necessarily, at least initially, meant to be there.

There ended up being a lot male vocal religious-sounding arrangements on the score. That wasn’t initially an intention, but it sort of ended up happening because Dave had written the piece that we call “Crucible.” It was originally written for a different scene. That section actually got rejected completely, and we thought it was just going to be a lost piece of music. It’s the vocal song that happens towards the end of the movie, when they’re running through the final crucible test. The film editor, in trying to put together an edit that worked, used that piece of music over the scene where they’re running across the obstacle course. It actually worked so well that it suddenly became this anchor, in a way, for the whole movie. That piece was initially lyrical all the way through, and because the drill sergeant starts to speak toward the second half of that scene, we got a note about figuring out how to remove the lyrics and have it become instrumental. We re-recorded the second half of the song to just be a male vocal arrangement, and I think that came out in a way that got Elegance so excited that he started to kind of be like, “Can we get that again?” Then we started going back and placing that theme throughout, but it wasn’t actually an initial aim of the film at all. In fact, it was during the eleventh hour. All of the vocal recording that has that gospel-y, religious touch happened in the last week and a half of the score work that we did.

Filmmaker: Speaking of the recording process, did you record the score remotely as you did with Time Skiffs, or were you able to get into the studio together?

Dibb: This was 100% remote.

Filmmaker: Is this a process you’ve become super comfortable with?

Dibb: Yeah. I mean, there are certain things that we would not be willing to do under those circumstances. Not to divert, but that’s part of the story of Time Skiffs and the following record that comes out of that. We’d written a bunch of music, and it was all ready to go when we had to do Time Skiffs remotely [due to the pandemic]. A lot of that [album] was about winnowing out what we felt like we could do in that context, and getting rid of the things that we had to absolutely be in the same room for. But for this particular process and the needs of this score, it felt like it worked really well.

As much as we all love being in a studio together and in some ways would always choose that, I think that we did find the silver lining of the Times Skiffs process. It lent itself very well to film score work. It gives the individual a lot of time to be in a creative process without the pressure of having someone staring over their shoulder, looking at them through the glass. I know that I particularly—and I feel like Brian probably feels the same way—feel like you can spend some time workshopping ideas, and then be in a cocoon for a period of time in a way that works really well. For other scores, I’m sure that would not be the case. If we were, you know, needing to arrange for strings, or if we wanted to do something as musicians playing off each other, we’d need to be in the same room to see visual cues or things of that nature.

Weitz: It also helps, when time is limited and there are a lot of cues to do, to divide and conquer. Especially because we each have different strengths and sensibilities in the band, and emotions we connect with on stronger levels than others do. If it was like, “This cue needs to be really melancholy,” a certain person would take it. Or, “This needs to be kind of dark and scary,” then a different person takes over. Even with the instrumental palette, if something needs to be synthy or have drums—Noah [Lennox, Panda Bear] wasn’t super involved in this, but if we needed live drums, that’s when Noah would come in and be like, “All right, yeah, cool.”

Since the internet allows you to be in constant contact with everyone, it was almost like being in a studio, just with the four of us in different rooms. We worked on different cues at the same time, and could then quickly send things around to people and ask, “How does this feel?” Or we could say, “Hey, I could use this [sonic] element that I can’t actually create myself. Can somebody else put that on there? Josh, can you play piano over this? Noah, can you play drums over this?” It was like a virtual workshop space. We were in contact all the time, but it helped us to identify cues where it’s like, “This is in my wheelhouse, this is in your wheelhouse. Let’s just start there and work simultaneously.”

Dibb: Yeah, there are multiple cues throughout that are entirely Brian, or entirely me or entirely Dave. Nobody else played.

Weitz: Yeah, and Crestone’s the same way.

Dibb: A lot of it, yeah. I think it’s interesting to come away from a process like Crestone or The Inspection. It’s a cohesive score now, but it came out of this place where people are, in many cases, working completely on their own. Obviously, quite a few of [the cues] were mostly Brian, but then I came in and added a vocal thing. Or something was mostly me, then Brian added some sound. Then there are, of course, plenty of crossover moments. But in many ways, it is, as Brian said, a “divide and conquer” situation.

Filmmaker: You’ve been speaking about this process and using phrases like “next time” or “next score.” 12 years after your first filmic collaboration, do you feel that you’ll continue embarking on these projects as a band?

Dibb: Given the opportunity, it’s something that a few of us enjoy quite a bit.

Weitz: I’d love to do it. I mean, I love doing Animal Collective, making records and touring. But with the time we’re not doing that, I could do this all day.

Filmmaker: I’m glad. Studio interference can sometimes really sour that sense of creative collaboration. It’s nice that it wasn’t too daunting or imposing during this process.

Dibb: It’s definitely new territory for us. I mean, this was a great process and there’s nothing to really complain about. But I think feeling those frictions are just new experiences for us as a band. We don’t work with producers that have any sway over what we’re doing. Our label never has any sway. It was a new sensation, and I can imagine instances where it’s really aggravating. But that’s part of the work. I can imagine accepting that.

Filmmaker: Finally, Indigo De Souza is also listed as a collaborator on the end credit song “Wish I Knew You.” How did you come to work on that song with her?

Dibb: This is an answer that really should be almost entirely for Dave. He wrote that song and recorded it. I think you added some sounds to it, though, right Brian?

Weitz: Yeah, I added a few little things here and there.

Dibb: We all know Indigo, but Dave lives in Asheville and she lives there, too. His girlfriend actually manages Indigo. So he wrote that song and recorded all the vocal parts himself, knowing that Elegance ultimately wanted it to be a duet between Dave and somebody else. Elegance had a lot of different ideas of who that other person could be, but at a certain point we just needed someone in there and Elegance hadn’t nailed anyone down. Dave was like, “Why don’t we get Indigo to do it? She has an incredible voice.” I think with them both being part of the same community and never having had the direct opportunity to collaborate before, it just seemed like an easy fit. Talking to Dave, it seems they have a really great time doing it. It actually may be leading to them working on more stuff together.