Back to selection

Back to selection

“Sex and Sexuality Have Been Central to All of My Movies”: Gregg Araki on Restoring The Doom Generation

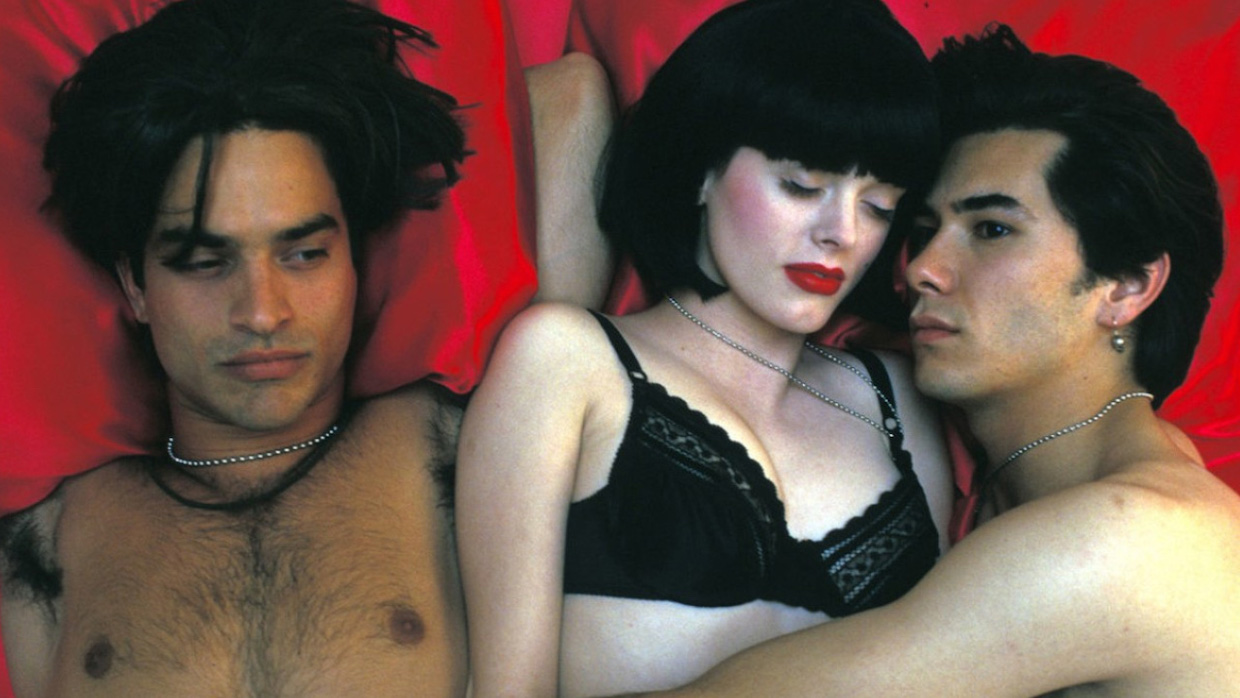

Jonathon Schaech, Rose McGowan and James Duval in The Doom Generation

Jonathon Schaech, Rose McGowan and James Duval in The Doom Generation The tongue-in-cheek title card for The Doom Generation—“a heterosexual movie by Gregg Araki”—isn’t merely an enduring “fuck you” to homophobes. Amid a sexless and puritanical American film landscape, coupled with an equally regressive online discourse on whether sex scenes in films are ever truly necessary, the emphasis on a sexual movie by Gregg Araki, regardless of orientation, transmits a much-needed erotic jolt.

Newly restored in a 4K director’s cut, with grisly moments previously nixed for an Araki-unapproved R-rated cut now restored, The Doom Generation follows a trio of heartthrobs on a road trip from hell. After a night out clubbing, teen lovers Amy Blue (Rose McGowan in her first leading role) and Jordan White (early Araki muse James Duval) are hooking up in the former’s beat-up car—or at least trying to, as Jordan can’t quite get it up due to intense AIDS anxiety. Driving back home through the outskirts of L.A., they pick up a mysterious hitchhiker, Xavier or “X” (Johnathon Schaech), who immediately charms the sensitive Jordan. Acid-tongued Amy, however, isn’t as pliable and kicks X out of her car the first chance she gets. When she and Jordan end up at a convenience store for a late night nosh, they realize they’re short on cash and the aggravated cashier pulls a shotgun on the duo; Xavier reappears just in time to accidentally blow the guy’s brains out. The three go on the run and hide out in a string of seedy motels, where Amy and X become sexually entangled, though their tryst isn’t kept secret from Jordan for long. (“You’re like a life support system for a cock!” Amy exclaims when X spills the beans to her boyfriend.) As it turns out, X isn’t content to just sleep with Amy, and the erotic tension between the sexy drifter and meek cuckold mounts until the film reaches its violent climax.

In an interview with Filmmaker for the fall 1995 issue, Araki made it clear that teens are often drawn to his films, and he finds it infantilizing to label certain movies as unfit for their viewership based solely on whether it possesses violent or sexual content:

I’ve had kids as young as 13 tell me that it was one of the best movies they’ve seen. You might think that such young kids would find the film too horrifying, but my experience has been that kids are pretty hip, smart and too media-savvy for the violence to seem that significant to them, which of course is part of what Doom is about.

Araki’s first “big budget” film (just under $1 million) and the second entry in his Teenage Apocalypse trilogy, Doom is rife with dreamy (or nightmarish?) production design, emphatically ’90s teen-speak and an even more era-appropriate soundtrack. Like all of Araki’s work, it is boldly transgressive but never baselessly cruel, depicting the netherworld between radical queer relationships and the homophobic dystopia we actually inhabit.

The writer-director spoke to me ahead of two sold out Q&A screenings in New York City this week, first at BAM as part of NewFest’s “Queering the Canon” series and then at IFC Center, discussing the Sundance premiere of the Doom 4K restoration, the lack of sex within the American film landscape (and what this means for young people), his ongoing qualms with Coachella and much more.

Filmmaker: The Doom Generation hasn’t been readily available to view for a while now, so I’m curious what set this restoration in motion now, 28 years after its Sundance premiere.

Araki: Basically, I’ve been wanting to do it—and we’re also doing one for Nowhere later this year—because [these films are] not available. For historical and archival purposes, eventually all my films will be [available] so people can see them. Doom and Nowhere, in particular, have a kind of intense cult following. The original DVD release of The Doom Generation—and this is back in the freaking ’90s—is terrible. It’s a pan and scan and not very good quality. While doing the remaster, I was reminded that it’s a gorgeously shot film. Jim Fealy, an amazing cinematographer, shot it. We hired him because he used to work with Bruce Weber a lot and did a bunch of music videos and commercials. Recently I noticed on his IMDb that he’s been doing Beyoncé music videos [laughs]. So, we hired him specifically because I wanted the film to have this kind of gorgeous look. And the production designer is the late, great Thérèse DePrez. We had a very tight budget—under a million dollars, which wasn’t much money—but they both pulled out all the stops and it’s such a gorgeous movie. And the cast has never been more beautiful. They’re just at the peak of their beauty, all three of them.

When we were remastering [the film], I was just like, “Wow, I can’t believe that this hasn’t been properly seen basically ever.” When Doom Generation was theatrically released in the ’90s, it was barely released in the theater for a week or two. [It screened] in LA, San Francisco, Seattle—you know, certain cities—so it’s really lived all this time on these inferior video copies. So, the fact that people still care about it, even though they’ve never really seen it as it’s supposed to be seen, was a big challenge for us. It was definitely worth me devoting the time to personally recolor the whole movie. We remastered the sound as well, because some of the dialogue was hard to hear, particularly because the music has an amazing ’90s soundtrack of all these incredible bands. I guess I didn’t know how to mix or edit music back in the ’90s, but the music was not as punchy or used as well as it could be. We fixed all of that. Having just seen it at Sundance with an audience, it’s just rocking [laughs]. It’s really meant to be seen like this, and I’m so excited for people to see it in a theater. If you can’t see it in a theater—if you live in Alaska or something—definitely see it on a high quality Blu-ray or a streaming service and play it loud, because it’s pretty fun. It’s a very cinematic experience now, and I’m so excited that it’s finally available as it should be.

I hope that this new version of it wipes those old copies out entirely, because they’re so inferior. There was an R-rated cut of Doom Generation that was made without my approval, and it’s terrible. It’s literally been butchered beyond recognition, and I’d prefer that people don’t watch it at all than watch that copy of it. I was very vocal about how I didn’t want people to watch it at the time, but I’ve seen it floating around on YouTube and the internet. I hope that version dies forever now. This is the new, definitive version, the only one that should be seen.

Filmmaker: Speaking of that, I watched the film for the first time as a teenager, definitely on one of those virus-laden internet sites in, like, 2009. I probably enabled a bunch of pop-ups on my family computer [laughs]. But upon re-watch, it almost felt like I was watching something I hadn’t seen before.

Araki: When I was remastering it, I was like, “Wow, this is like a completely different movie.” Even I forgot so much of it. It was like making a new movie, almost. It was funny: Andrea Sperling, one of the producers, has kids who are teenagers and she was like, “I keep telling kids to watch Doom Generation; your mom’s hip, you know. I made The Doom Generation.” I said to her, “You want your kids to watch this movie? Really? It’s pretty intense.” Then she saw it at Sundance and was like, “Oh my God!”

Filmmaker: She realized she had to walk her recommendation back a bit.

Araki: Yeah [laughs]. She’ll maybe wait a few years before her kids can see it. It’s an intense movie, but I do think it really holds up. It’s also 83 minutes! It just flies by. Like, “Whoop, it’s over already.” It’s a fun ride.

Filmmaker: Because it’s such a brief movie, I’m also curious what scenes you re-included in the restoration that were originally cut from the ‘90s theatrical version?

Araki: Mainly from the last reel, the sort of climactic massacre.

Filmmaker: Yeah, I thought so.

Araki: There’s some stuff in there that we cut out—I think at the request of the U.S. distributor, I don’t remember exactly— just to make it not quite so intense. We tracked all that stuff down in the original materials and added it back in. The ending of the movie has always been intense, but now it’s even a little more intense.

Filmmaker: As a teenager, I was a total junkie for transgressive cinema. It was my bread and butter. So, watching The Doom Generation now, I was like, “Oh my God, why did the ending jolt me a little bit more than I remember?”

Araki: It’s basically the same, just a little more graphic and intense. And watching in a theater was really intense [laughs]. When we were at Sundance, I just assumed [the audience] would be people like you—people who’ve seen it before. Before the screening, I asked, “How many people have never seen the movie before?” Literally 80% of the audience had never seen it. It was a whole new audience and a very young audience. It was cool.

Filmmaker: I actually wanted to go into that a little bit more. As you were saying, you were recently at Sundance with the film, and you have a long history with the festival. You started there with the living end in ‘92 and most recently premiered your film White Bird in a Blizzard.

Araki: And there was Now Apocalypse in 2019!

Filmmaker: Yes, of course, the first few episodes of your series! Because you’ve had such a longstanding history with the festival, I’d like to know a bit more about what it felt like to be back, especially since COVID.

Araki: We screened at the Egyptian, which is where our world premiere was in 1995. It was literally like returning to the scene of the original crime [laughs]. Throughout the ’90s, Sundance was a big deal in the independent cinema world. Now it’s become such a big part of the cinema landscape in general. The idea that these indie movies can go on and become best picture winners…[laughs]. Everything is shifting. To be screened there in 2023 alongside the new crop of what’s cutting-edge and coming next was super, super exciting.

Filmmaker: The film has pretty pivotal moments of gorey violence, which are arguably more shocking than any of the sex scenes. This was your first big budget film—did having that extra money and production resources prompt you to dabble more overtly in the grotesque? It was a big leap for you.

Araki: It wasn’t the extra money, per se. We did have some crazy gore in The Living End, which we made for $20,000 [laughs].

Filmmaker: Nothing as bold as a talking, decapitated head, though!

Araki: [Laughs]. Well, we had a guy getting stabbed in the head in The Living End, you know what I mean? But yeah, we had a few more toys to play with at a larger budget, a lot of effects stuff. There was a guy who was almost like an intern, a friend of mine at UC Santa Barbara, along with Andrea, when I taught an indie film class. He was a gore effects hobbyist, so he contributed a lot of the head and when the body tips over and the blood comes squirting out.

The thing about Doom Generation was that we were young and just wanted to make something really subversive, punk, transgressive and rebellious. Nothing was too extreme for us. The example I think of is the scene where Johnathan licks the cum off his hand. My memory’s not great these days, but I don’t think that was in the original script. I remember it was during the rehearsal—actually, I think it was when the effects guy was telling Jonathan, “This is what the [prop] cum is like, and it is edible,”just to emphasize that it wasn’t toxic or anything. My recollection is that Johnathan came up with the idea of licking it off his hand. Andrea was there, too, and I was just like, “Should we do this? Is it too much?” And she said, “Oh yeah, let’s fucking do it!” That was the attitude, to just push the envelope. It wasn’t like, “Oh, I’m worried we might turn people off,” or “We want mainstream approval,” and it became one of the most iconic scenes in the whole movie, because people were so outraged by it.

Filmmaker: I want to talk about the recurring motif in the film of the characters being charged $6.66 for their various purchases. The film takes place a few years after “Satanic Panic” really reached its peak, but even the newscasters in Doom allude to the suspects being queer Satanists. It’s like a melding of broader American anxieties of queer and Satanic panic, which emphasizes the hysterical ridiculousness of both. But the repeating number also feels foreboding and like it’s establishing that the characters are indeed in hell, and the “punishment” for their sins is encroaching. How’d you navigate the film’s satirical elements while incorporating that very real-life homophobia into the film’s climax?

Araki: I remember I was talking to IndieWire before Sundance this year [about] the violence, homophobia and Nazis at the end of the film. You know, queer culture and queer life has really shifted a lot since the ’90s. Unfortunately, the homophobia and the neo-Nazis are almost worse than they’ve ever been. But at that time, the big threat—like in The Living End and Totally Fucked Up—was gay bashing. There was a sense of being vulnerable, always having to have your guard up. The threat of violence was always looming over people, so I think that the ending of Doom Generation was pretty much a manifestation of that paranoia. But I was also hugely influenced by David Lynch. People have talked about [Doom] being kind of campy in places, and I’ve always thought of it as being more surreal. I was always talking about surrealism and nightmares when it came to the design and tone of the movie. These characters are in this nightmare world, and this gave us the creative freedom to have the red room and the black-and-white checkered room, you know what I mean? All of these things that existed in the borderland between fantasy and reality. That’s where the whole movie is pitched. I remember Marcus [Hu, longtime producer and co-founder of Strand Releasing] and I were talking about the ending of the movie, which in particular is so strangely stylized and feels like a nightmare, and how it feels like it’s not real. That was something that I was very intentional about while we were making it—pushing everything to this limit of reality. That was the thing about the newscasters, too: they were Lauren Tewes from The Love Boat and [Christopher Knight, who played] Peter Brady! The idea was that these people are sort of ingrained in your subconscious. To me, it wasn’t a cheesy cameo so much as it is like the way when you’re dreaming, people from TV and movies pop into your head. I remember when we were casting all of the smaller parts, I told the casting director that I wanted everyone not to necessarily be “famous,” but recognizable, so that it feels like the way people pop into your dreams.

Filmmaker: They say that you’re unable to conjure a face you haven’t seen before in your dreams.

Araki: Exactly. They’re all faces that you at least vaguely recognize, like Heidi Fleiss and Perry Farrell.

Filmmaker: Re-watching this film now made me painfully aware of the fact that sexuality and eroticism of any kind are very much remiss from the current film landscape in general. What do you think is the reason for this? Is there any recourse here?

Araki: I was just thinking about this. I was reading a piece today talking about sexuality in movies. For me, it’s something that [stems] from my generation, when I went to film school, and the influences that had a big impression on me when I was a young, budding filmmaker. Sex and sexuality have been central to all of my movies. Those early Almodóvar movies, particularly Law of Desire and Matador, were so influential to me. Fassbinder movies, like Querelle, are really what made me want to make movies.

One of the things about sex in my movies is it’s never meant to be titillating. [laughs] That’s why, to me, the proliferation of pornography is great, because it sort of [distinguishes] that films are not porno. If you want to watch porn, just watch porn! It’s so easy. Sex in my movies has always been about a character’s most intimate moments and their secrets; you see a side of that person during sex that no one else sees. The analogy I use is that if you’ve had a one-night-stand with somebody, they know you in a way that your mother or best friend could never. Your true character is revealed in those really intimate moments. Those moments are the ones I care about.

To me, everybody has their public persona that they put on—like I’m putting on right now [laughs]. That’s the thing about sex and sex scenes: when you’re naked, you’re physically, emotionally and spiritually naked. I remember when we made Doom Generation, I literally told the producer, “I want this to be like Last Tango in Paris for teenagers.” I wanted it to be literally like X-rated, because I wanted it to push those boundaries and just really be about those moments. Watching the movie now, I was thinking about how at the time, it was so racy, shocking and controversial. Now it seems so tame to me.

I do think there is a shift away from sex and sexuality, which is personally not interesting to me. At the same time, there’s a shift in the other direction, like with Euphoria and The White Lotus, which is kind of interesting. I’ve been particularly influenced by European cinema—Doom Generation and most of my other movies were financed by French companies—and the French are much less uptight about all of this stuff.

I remember when we were on the Now Apocalypse press tour, Roxane Mesquida, because she’s done a lot of nudity and sex scenes in her movies, was asked by a TV critic if there were intimacy coordinators on set. And she was like, “No, what the fuck do I need that for? I know what I’m doing, I’ve been doing this since I was 18.” The French have a different attitude about it, which I think is refreshing. Anyway, that’s my take.

Filmmaker: Yeah, I feel like within the current landscape, it’s rare to find American films engaging with sex and sexuality. Typically you’ll need to look abroad.

Araki: It’s unfortunate. I would never force an actor to do nudity, but my projects are upfront when we’re casting. When we did Now Apocalypse, we were very clear about saying, “This is gonna be like HBO-rated sex. There won’t be a full frontal, but there will be this, this and this. And if you’re not comfortable with that, do not come in to audition, because I don’t really want to see you.” That’s the approach I normally take with most of my projects. There’s no confusion about it.

Filmmaker: The most recent film I’ve seen that dealt with explicitly gay teenage sexuality was this Australian filmmaker Goran Stolevski’s Of an Age, which came out a few weeks ago.

Araki: I actually think someone was just telling me about this movie.

Filmmaker: Yeah, it was loosely inspired by the filmmaker’s own erotic awakening and coming out. Aside from that, though, it appears that queer sex has taken a backseat to queer representation on screen. What are your thoughts on this general trajectory and the current “queer film” landscape? Why is sex generally lacking from these narratives?

Araki: Speaking as a filmmaker, [the shift toward sexless representation] is just not as interesting to me. I do think they’re both important, and I think that it would be great if they’re both represented. There is the argument that being queer is not just about sex or whatever. But at the same time, isn’t it? [laughs] My co-writer on Now Apocalypse was Karley Sciortino, and I call her the Carrie Bradshaw of the new [generation]. She writes a Vogue column on sex, sexuality and relationships. We have a lot in common. We’ve talked about how sex and sexuality has been a driving force in my life. In a way, I feel like if it wasn’t for sex, desire, lust, adventures—these things that I’ve done in my life and relationships that I’ve had—I wouldn’t have an identity. Those experiences are what makes me who I am.

That’s why my movies are all about that. If I had grown up in a super conservative environment, married my high school sweetheart, had two kids and never left my tiny town, I definitely wouldn’t be here [laughs]. My whole identity is based upon searching, going outside of this little bubble. Sex and sexuality are probably the primary forces that move you outside of a comfort zone and lead you to other parts of yourself. To downplay [the value of] that experience, to me, is not really authentic.

Filmmaker: I totally agree. For many of us as teenagers, especially queer people, one’s sexual identity is like the first space you’re able to authentically explore yourself. To me, it’s confusing why we would move away from that and make everything so chaste, all about true love and sentimentality. A lot of the time, growing up and navigating your identity is anything but being kind.

Araki: Yeah, it’s all about learning to navigate sex and love. I mean, if you have a sex addiction and it’s out of control for you, then that’s a problem. But the notion of learning about yourself is so tied into sex. That’s why I find this shift super unnerving. Hopefully Doom Generation [being re-released] will help shift the course. I was reading this article talking about young people, and it said that some ungodly amount—like 30% of Gen Z—doesn’t have sex, or have never had a relationship. So much of that relates to technology, people being so isolated from each other and just texting. But that connection to people, I think, is so important to being human and becoming a person.

Filmmaker: This also reminds me of what you were saying earlier with Doom’s cum-licking scene. Obviously, that brought me to the parallel of Call Me by Your Name when Elio eats the peach. But young people still talk about being very against that movie. They say that it basically condones pedophilia.

Araki: Young people are against that movie?! Timothée Chalamet is in it, how could they be against it? I mean, Armie Hammer is in it, so that’s understandable.

Filmmaker: I mean the conversation is ongoing, but even when it came out, people were like, “Oh, depicting the age gap is unacceptable and it’s pedophilic.” I’m sorry, but labeling an openly gay filmmaker as a pedophile is verbatim a conservative talking point.

Araki: We really must be in different circles, because I haven’t heard this.

Filmmaker: God, maybe I just spend too much time scrolling through TikTok and Twitter.

Araki: Guess I’m not on TikTok! One thing about Call Me By Your Name is that it’s a period piece set in the ‘80s, so it’s a completely different time. That’s probably why I related to it so much, because it’s my generation. Those are my stories, those sort of relationships. That’s why movies like Doom Generation are so important. Somebody told me the other night at a party, “Nowhere made me gay.” These stories, and this idea of sexual awareness and sexual experience, are very important.

Filmmaker: Especially among teenage protagonists, which feels sort of not okay anymore.

Araki: What I have to say to these young people, I guess, is: when you’re young, that’s when you’re doing your most exciting and dramatic exploration, growing and making. You can have relationships that are a mistake. You can make mistakes. That’s part of growing up: “Oh, well, that relationship didn’t work for whatever reason. But I’ve learned from it, I’ve grown from it.” It’s like the X character in Doom Generation. He’s hot, he’s seductive. Is he bad news? Yes. [laughs] Is he boyfriend material? No. Is it a mistake to sleep with this guy? Probably.

Filmmaker: Right. The point is that you want to do it anyway.

Araki: Yeah! When you’re young, that’s when you make those mistakes. I always tell the kids: as long as you don’t get pregnant or get AIDs—have safe sex, at least—mistakes aren’t that big of a deal, because you learn from them.

Filmmaker: There’s a reason why people, like me, were seeking out your films on pirated websites when we were 14 years old. It felt amazing to have access to somebody who’s bold enough to say, “This is cool, actually. You’re not the devil for wanting to do something like this.”

Araki: There’s a real danger with sex negativity, because it’s in lockstep with Christian fundamentalism and the idea of being celibate and all of this crazy shit. My films have always been very sex positive. There’s a reason why, as a young person, your hormones are raging. That’s your body telling you that you need to get out and explore. That’s how you grow up, you know?

Filmmaker: Expanding on that, your films have always been attentive to subculture. You’ve stated in the past that you’re “very interested in alternative culture and the rebellious, different, outside-the-mainstream thing.” I’m curious as to what might be piquing your interest when it comes to youth countercultures right now, if anything. In my opinion, it doesn’t feel as robust among young people as it did even when I came of age in the aughts and 2010s. It’s a lot of aesthetic recycling and ideological uniformity. Maybe you’ve seen otherwise.

Araki: Maybe it’s because I’m old, but I do feel like, [self-mocking tone] “Kids today don’t know what’s great!” [laughs] The barometer I use is Coachella. I’ve been to Coachella, I don’t know, like 15 times, or at least it’s in the double digits. I remember when Coachella started, from the early 2000s up to probably 2015, it reminded me of Nowhere. It felt like this utopian, sort of pansexual vibe. Beautiful young people and amazing music everywhere. That’s why I loved it so much!

Filmmaker: It’s your ethos.

Araki: It was literally like Nowhere came to life. These beautiful bi or omnisexual people—it was very cool and steeped in alternative culture. The Cure played, and Depeche Mode and Pixies, the Jesus and Mary Chain—all of these bands that were in my movies! Then it began to shift the closer we got to the 2020s, and the killer for me, the year I didn’t go, was Ariana Grande. It was like, “Why is she here?” This is supposedly an alternative place. I understood Jay-Z playing, but even he and Beyonce are hugely popular and mainstream. I understood that a bit more, though. But Ariana Grande? When you open the door to the complete middle of the road, it’s not going to be [very exciting]. I understand, “Young people don’t know who The Cure are,” da da da. This year, The Chemical Brothers and Björk are playing, so there’s that. [Coachella] is trying to find where they’re at, I think. But there is that sense of, in terms of culture as an old person, “Oh, we had it so much better.”

Filmmaker: I don’t know. I’m 28 and live in New York City and struggle to feel like I’m part of any discernible underground or subculture. It feels like everything’s been co-opted.

Araki: It’s always been that way. It’s like punk rock music. In general, alternative culture ends up getting larger and more incorporated into the mainstream.

Filmmaker: Doom’s soundtrack served as my entryway into The Jesus and Mary Chain and Slowdive. Music has been an enormous presence in your films, especially Gen X sonic staples. I’m really interested in how your relationship to music has potentially evolved over the years. Are there any contemporary bands that you’ve fallen in love with recently? Older artists you’ve rediscovered? Or have the bands that soundtracked your various films taken on new significance over the years?

Araki: We were talking about sex earlier, and how it has been such a motivating force in my life in terms of moving through the world and such a profound influence on my work. The other aspect of that is music. I came of age at the exact right moment for that alternative culture. When I was in college, post-punk and new wave music was big—Siouxsie and the Banshees, The Cure, Depeche Mode, Talking Heads and The B-52’s. Our tribe was defined by that. Me and my friends used to shop at thrift stores and dress crazy. We were all artsy and the music became such a huge part of our identity. Then it became about not being concerned with mainstream success and like, winning an Oscar [laughs]. It’s about being more concerned about this sensibility—your place as a sort of outsider in culture, doing something different and marching to the beat of your own drum. Between being queer, a punk rocker and alternative: without those I would be nowhere.

Filmmaker: But do you feel like because of the era you grew up in, you’ve gravitated toward the same bands that you loved when you were younger?

Araki: I mean, I don’t have Spotify or Apple Music [laughs].

Filmmaker: Good. Streaming is horrible for artists.

Araki: I have an iPod that has like 30,000 songs on it. I’m listening to it right now. I literally just put it on shuffle and listen to it all day long. It’s a mix of stuff I downloaded like last week and stuff that I’ve loved since the ‘80s, like The English Beat or something [laughs]. It’s got everything, and that’s what I think is cool. Coachella tries to do that, you know. They incorporate the Frank Oceans and whatever oldies stuff [those artists] came from, and it’s all sort of tied together by this “alternative” label.

Filmmaker: I really wish I still had my iPod classic.

Araki: The thing I love about listening to an iPod on Shuffle is that it’s completely random. I have so much music now, I always find it hard to pick something. It’s always like, “What do I wanna listen to?” It’s always so easy to go back to that Cocteau Twins album or Slowdive, the same thing over and over and over. But when you listen to an iPod and it’s on shuffle, it’s like, “Oh my God, I forgot all about this song.” I never would’ve said, “I’m gonna play this song today.” Being surprised by your own music collection is the way I like to live my day-to-day life.

Filmmaker: It’s much better not to fall victim to the dreaded algorithm.