Back to selection

Back to selection

“Let’s Make It Feel Like You’re Watching TV During Y2K”: Directors Brian Becker and Marley McDonald on Time Bomb Y2K

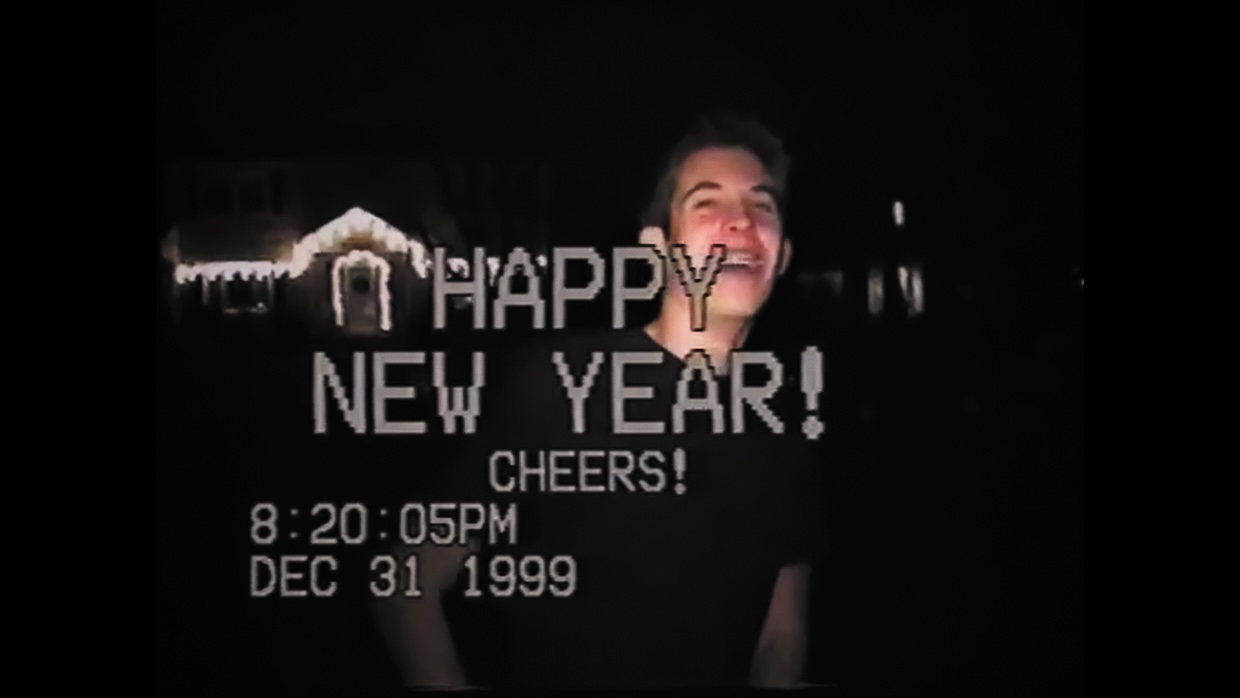

Time Bomb Y2K (courtesy of HBO Documentary Films)

Time Bomb Y2K (courtesy of HBO Documentary Films) Where were you on December 31, 1999? Despite years of hearing Prince’s pleas to party, many Americans spent the evening at home, bewitched by a bizarre mix of sentimental reverie and fear. The end of the century, it turned out, was a time for reflection and mild panic. Media coverage warned that computers might register the year 2000 as the year 1900. Chaos could ensue, and you did not want to be caught in the club when the “millennium bug” caused the lights to go out and nuclear warheads to whirl mid-air. As Lisa de Moraes wrote in the Washington Post ahead of New Year’s Eve in 1999, “What are you, nuts? Didn’t you see NBC’s Y2K: The Movie last weekend? Haven’t you been watching Dateline? You gotta stay at home.”

Brian Becker and Marley McDonald resurrect this surreal, technophobic moment with their documentary Time Bomb Y2K. McDonald served as an associate editor on All the Beauty and the Bloodshed and additional editor on Listening to Kenny G, while Becker worked as an archival producer on MLK/FBI and Free Chol Soo Lee. The pair met on Matt Wolf’s Sundance hit Spaceship Earth, where they would “gchat movie ideas back and forth,” as Becker told me, until they landed on an idea to explore the Y2K bug. The resulting film marks both of their directorial debuts.

An all-archival affair, Time Bomb Y2K is a collage of existing footage from the mid-to-late-1990s, just up to the day after New Year’s Eve. The film draws from roughly 100 licensing sources, ranging from major news broadcasters (CNN, ABC, BBC) to archival libraries (CONUS Archive, Kinolibrary, Prelinger Archives) to New Year’s Eve home videos. The filmmakers and their seven-person team scoured about 700 hours of archival footage to mix-master an 84-minute film. (That time grew in late 2021, when Becker and McDonald successfully pitched the project to HBO Documentary Films.)

Time Bomb Y2K eschews cheap laughs or easy nostalgia (though, it must be said, it does induce nostalgia and laughs). It is, instead, a kaleidoscopic portrait of a nation in the face of an existential threat, as rendered by the news coverage and pop culture marginalia of the era, whose rediscovered central characters include computer-engineer-turned-Y2K-pundit Peter de Jager and President Clinton’s Y2K czar John Koskinen. The film was born during the peak days of another crisis, the COVID-19 pandemic, and viewers will find parallels to numerous emergencies buried within these standard-definition, 4:3 images. At its core, Time Bomb Y2K operates as an object lesson in how society copes with destabilizing uncertainty, from hyper-competence to doomsday paranoia.

The documentary premiered at the True/False Film Fest in March and has since screened at more than 20 festivals worldwide. DCTV’s Firehouse Cinema in New York will host its theatrical run from December 15 to 21, then HBO will broadcast the film just before New Year’s Eve on December 30. After meeting Becker and McDonald at the Hot Docs International Film Festival in Toronto, we got together months later and began our conversation by discussing the film’s year-long festival run.

Filmmaker: What has this last year been like for you two?

McDonald: A celebration of all the work we put in the two years prior. We’ve both worked on documentaries for a decade now. Normally, you go to one premiere, then that’s it—the film is over, and you have to deal with your separation anxiety from this long-term project. With this one, we’re getting as long of a run as we put into the edit.

Filmmaker: What was the genesis of the film?

Becker: I’ve worked as an archival producer, story producer or some combination of the two. There’s so much watching involved in any project that you’re researching, you inevitably come across material not related to the topic at hand. I’ll often discover material and follow that curiosity on my own, investigating whether more footage might exist and whether that footage feels resonant, emotional or interesting. Then, it hits you: “Here’s this major event from my childhood that I haven’t thought about since it came and went.” That led to further research and realizing it was on TV essentially every night for two years, so there was more where that came from.

McDonald: We had picked up a few ideas and played around with them, then this one came and it was like, “Oh, this movie has to be made, and we have to make it.” The more we dug into it, it presented itself as an existential crisis that America went through. And we thought, “What can we learn from that in the summer of 2020?”

Filmmaker: Did you always envision it as an all-archival film?

Becker: Yeah, I think so. It’s a first film, so as far as funding goes, we [thought] to ourselves, “Maybe we can cobble together this really immersive experience that also relies heavily on fair use [footage] because we don’t know what type of funding we’ll get.” The more we worked, the more we realized that was a bit limiting, and we wanted the full access to network archives that you can only get from licensing materials. But the idea of keeping it entirely archival and as immersive as possible was something that got stuck in our heads from the start.

McDonald: By setting those limitations, new freedoms emerged with how we were going to edit this film. It’s a totally different process than making a radio edit of an interview and then finding the right B-roll to sit on top of it.

Filmmaker: A lot of documentaries that deal with nostalgia rely on present-day interviews with experts and celebrities. You were never tempted to go there?

McDonald: Oh, we were tempted [laughs]. But we had set this limitation, and we kept confirming throughout the process that it could be this way. Of course, there were those moments in the edit where you’re like, “If only we could find [somone] saying this exact thing.” A lot of the luxury of doing interviews is guiding someone to say the thing that you’re missing.

Becker: In the depths of rough-cut hell, it was really hard. Usually, you know a theme or a statement that you want to include in a film. In our case, you’re itching for that ability to just call someone and have them say something. For this film, it meant diving back into our archive of material. This is where I and my fellow archival researcher and co-producer Peter Nauffts, associate producer Shelby Fintak, assistant editor Katyann Gonzalez and production assistant Kushagra Kar would put our heads together to watch footage and send selects around and bounce ideas off of each other. Then, I’d go sit with Marley and [co-editor] Maya Mumma and discuss the ideas, and they would come back and tell us what we were still missing. Eventually, somewhere in that pile of footage, we would discover exactly, or close to exactly, what we wanted. If we didn’t have it, we would just dive back into researching.

McDonald: What was found would go into the edit, and that would inspire new ideas that the archival team would have to go find again. Brian and I wanted it to play out collaboratively. We’ve had the experience of working on a lot of films where you spend all these hours looking at footage, and sometimes no one asks you, but you have ideas. We wanted to make that space for our team to make sure they felt that the things that they were interested in were represented.

Filmmaker: The lack of talking heads or explanatory titles really plunges the viewer into the period. Was that sort of timeless quality something you were going after—for the film to feel like an artifact of the time as opposed to a film made in the present day?

McDonald: We were always inspired by the period, the aesthetics, the music, the graphics and the 4:3 [ratio]. We wanted to make something that felt like you were in the time, but that the film so completely feels like a time capsule emerged just from the limitation we put on ourselves. Once we realized that’s what was happening in the edit, we were like, “Let’s lean into that as far as possible. Let’s make it feel like you’re watching TV during Y2K.”

Becker: Having grown up in that era, we have a particular fondness for those tape formats in the late ’90s. Leveraging nostalgia as an endpoint for audiences is useful, but we didn’t want it to be a purely nostalgic trip. Nostalgia is kind of…

Filmmaker: It’s a nice bait.

Becker: It’s a useful endpoint to leverage, but we didn’t want to create something that was pure nostalgia, or else we would have made the movie entirely about celebrities, silly quotes and fashion. Nostalgia is like when you remember something and erase all the bad stuff. It’s purely remembering the halcyon days of the ’90s before 9/11 and the recession.

Filmmaker: How does one begin to shape an all-archival narrative? Do you immerse yourself in the footage and find themes and patterns, or do you have themes and patterns already in your head and look specifically for clips to match them?

McDonald: Both, I think. Every project starts with an idea. The most important part is acting on the idea. Then, while you’re in the idea, you have to forget the original ideas and go with what you’re actually creating. How we start crafting it is, we start making connections between the things you’re seeing. For us, we collected at first a bank of maybe 100 clips. You watch through it all and are like, “What are the things that are reappearing? What’s standing out?” Editing is about being the first audience to the footage, really trying to know yourself enough to know why you respond to certain things. With the amount of footage that we had, it was very crucial that we all participated in that stage of editing—watching footage and really understanding what made us feel and why.

Becker: The other thing that we would constantly look out for were connections to the present day. In lieu of interviews, we looked for little curls of wisdom or philosophy or introspection that could bring us back to what we were living through.

Filmmaker: And how were you collecting those clips?

Becker: For me, it’s years of experience doing archival research—finding collections, ordering digitizations, using old text records. A lot of these places have a file cart system that was turned into a Word document at some point in the early 2000s. So, we used those one-sentence to one-paragraph descriptions to see what’s worth digitizing.

Filmmaker: To take one example, there’s a really random clip of Matt Damon on the press tour for The Talented Mr. Ripley talking about nuclear stockpiles. How on earth does one find a moment like that?

McDonald: That’s a contentious clip!

Filmmaker: Contentious how?

Becker: Just that Marley and I disagreed about whether it was good. It happens all the time. It’s a challenge of co-directing. That’s why it was useful to have Maya and the rest of the team weigh in. That clip was from the CONUS Archive. These are people I’ve worked with for almost 10 years. They have a lot of archival from the ’90s. They had a clip of celebrities—

McDonald: Mostly just the cast of The Talented Mr. Ripley. [laughs]

Becker: These were clips that I downloaded in the first days of research. When you have this much footage, it’s easy to lose sight of it, which is, again, why research is so important. So, when I was going back, I wanted a little more pop culture and levity with celebrities predicting what they thought would happen in that moment. So, coming back across that clip after having not seen it in a year, I sat at my desk and thought, “This is what I was looking for.”

Filmmaker: How does ripping footage off of YouTube come into play? Is that a pretty common tactic when you’re first assembling?

Becker: First assembling with no budget, yeah. You want a bedrock of material; then, I can trace that YouTube material back to its rights holder to get the real thing. We had a really intense process of finding home videos. We’d find stuff on YouTube and say, “OK, JohnZ1992 in Irving, Texas, uploaded this.” Peter Nauffts found this username, went to the guy’s profile and saw that the guy was uploading clips of a high school in Michigan. He was like, “If I search JohnZ1992 in this town in Michigan where his kid goes to high school, maybe that’ll give us some hints.” Then, you can go to the White Pages and look up all the John Zs in blank, Michigan. Then, you contact John Z and say, “Hey, did you keep your tapes?” Then, you’d get the tape and re-digitize it for a little better quality and license the footage from him. But other times, you call Melanie F., and she’s like, “Oh, I threw out all the tapes after I digitized them in 2008.” There’s stuff that’s just lost to the sands of time except for the fact that it’s on YouTube.

Filmmaker: For a film like this, how much of the budget goes to licensing?

Becker: It wasn’t a majority, but it was a large chunk of the budget. It’s funny because initially we thought all-archival was a way to save money. I know archival costs better than almost anyone—how naive I was! It would have saved us thousands and thousands of dollars to have someone saying things [in an interview] instead of in clips with Dan Rather or Brian Williams.

Filmmaker: The film has a number of recurring characters, people like Peter de Jager and John Koskinen. Are these people you found in the research, or were they people you were aware of beforehand?

McDonald: We weren’t aware of any of the characters; they definitely emerged. Peter de Jager is one of the first people you find out about when you start researching Y2K. He did thousands of media interviews. He actually sent us his interview schedule, and it was like five interviews before lunch, five interviews after lunch. He was just talking to everyone.

Filmmaker: So he participated in the film?

McDonald: Oh yeah, he was the first person we talked to. He was there from the very beginning to the very end, so we got to use him as this narrator. He was truly a blessing from the archive gods. The fact that he’s so gregarious and dramatic in his telling, you couldn’t ask for someone better to lead us through the film.

Becker: We have personal relationships with all of the major individuals in the film. I went to Peter’s basement outside of Toronto for two days. You can’t spend that much time in a small basement archive with someone, sifting through all these papers with a blessing of trust to go through all their personal materials, and not feel a responsibility to keep the film true to their story.

Filmmaker: There’s a version of this movie where you didn’t interact with those people at all, right? You could have just relied on licensed footage of them.

Becker: Yeah, we didn’t have to.

McDonald: But that would have been harder for us as well. They gave us so much information about the firsthand experience.

Filmmaker: I’m curious to what extent you consider the film a comedy. I ask because viewers’ impulse when they see wildly dated technology is to laugh, and I’m guessing there’s been quite a lot of laughter at the festival screenings.

Becker: I don’t consider it a comedy, but I think that documentaries could use a little more humor in them. This is a topic that allows for it. We didn’t want people laughing at characters, but I think a lot of the humor is, like you said, an ability to look at ourselves 23 years ago in relation to technology and to laugh at how simple it all seemed back then compared to now.

McDonald: I do think it’s partly a comedy. I wouldn’t say it’s a full comedy doc, [for] which we’re always on the hunt. But it is funny, and I think intentionally so. I was laughing a lot while we were making the movie. I wanted it to have that kind of lightheartedness, but like Brian said, you don’t want people to only laugh at the characters. That’s super important. Knowing when to shift tones was a huge challenge of editing. I think the movie starts very funny, then it becomes more serious, then gets a little more lighthearted again.

Becker: A big part of that challenge is the understanding of Y2K as a big hoax or joke. We’ve talked with so many programmers and activists [during production] who told us, “You’re lucky to think of it as a big joke. It’s because we worked around the clock for years to solve the problem.” So, to present this actual problem and massive cooperative effort between governments and the private sector as a big joke was something we had to be careful to avoid. We wanted to treat their labor with a real seriousness.

McDonald: People laugh a lot at the beginning of the movie because they walk into the theater thinking it was a joke. The hope is that throughout the movie they understand that it’s not and that there was this real problem.

Filmmaker: I’m very curious how you sourced the home videos.

Becker: The way I mentioned, from YouTube, was one way. We also collaborated with a nonprofit called the Center for Home Movies. It’s an amazing collection started by these archivists who work to discover, digitize and preserve home movies. Librarians and archivists made this film possible throughout. That partnership gave us access to their network of libraries and archives, and those locations individually put out calls for people’s videos. From there, we would digitize [the videos], send people their tapes back, send them a file and send them some money if we used it in the final film.

Filmmaker: By definition, Y2K turned out to be an anticlimax. How concerned were you during the making of the film, just from a narrative standpoint, that it ends with such an anticlimactic event?

McDonald: I was hugely concerned at a certain point in the making. There were two weeks when I was like, “New Year’s Eve cannot be the end of this movie. It’s never gonna work! Everyone in the theater knows it didn’t happen. How do you keep the tension alive?” Maya played a huge role in helping us expand our vision for the end of the film. She helped us see that this was a global, connected moment. All of these themes of interconnectivity could be shown visually through the celebrations across the world. She pulled that bite by Dan Rather where he’s like, “We defeated fascism and communism.” This was what people were feeling at that time. Once that was unlocked, it all made sense that it was this big emotional moment.

Becker: When we set out to [make the film], we thought the tension would increase until the last second. But the emotion of that time wasn’t pure terror. It was this weird jumble of hope and expectation for the next millennium, and also anxiety and fear over what would happen if all the lights went out as the clock struck 12.

Filmmaker: There’s something so foreboding about Vladimir Putin taking power that day, too. You feel like you’re really turning a page.

Becker: Oh, definitely. We thought it was worthwhile to include a handful of people who immediately bring you to the present.

McDonald: An important thing we wanted to get across in that last act was like, “OK, this crisis is over. What are we going to spend all of our media time on now?” It’s amazing that those things just arose in the archive: that Putin was handed power on 12/31/99 or that Rudy Giuliani was doing a press conference about Osama Bin Laden.

Filmmaker: We’re in this weird moment of millennial nostalgia right now. How much does it make you shudder to think your film may be viewed, quite literally, as millennial nostalgia?

Becker: When we started researching this, we hadn’t even heard of Y2K fashion. Our initial discovery of what the word “Y2K” meant to young people was because we were trying to research the millennium bug, and it’s fucking hard to find YouTube videos and Google articles because there’s an endless amount of TikToks and YouTube posts of teenagers being like, “I tried living like it was Y2K for a day.”

McDonald: It’s been really interesting releasing this movie over the course of a year. When we first started, a lot of the Q&A questions were like, “This is so much like COVID, this is like history repeating.” Then, we got into the summer, and everyone was like, “This is really reminding us of the fear around AI.” I think that’s a huge success for us, that we can use this movie as a vessel to explore the way that we respond to existential threats and crises.

Becker: We’re more than happy that Y2K fashion is still trending. We might get additional young viewers who have no idea what the millennium bug problem is to click on the movie and to end up seeing this much more complex film that isn’t just about low-rise pants. It’s not pure nostalgia. And I promise you we did not know [Y2K fashion] was trending this hard when we started. But did we mention it in all of our pitches once we discovered it? Of course we mentioned that in our pitches.

Filmmaker: There’s a lot of talk in the film about computer technology, both in utopian and dystopian terms. You have folks like Steve Jobs, who liken it to a “bicycle of the mind,” but also folks who make far more sinister predictions, some of which are fairly spot-on years later. Where do you fall on the utopian/dystopian spectrum when you think about how tech has advanced in the past 23 years?

McDonald: That’s so damn hard because I love technology. I think it’s helped create better art than ever before. It’s opened up so many possibilities and is a beautiful thing as a concept, but at the same time more middle-schoolers are depressed than ever before. It does not seem like society is benefiting at large from having access to the things that we have access to. It’s really hard not to let the dystopia take over. Every time I’m listening to the radio in the kitchen, my partner and I will be like, “Turn the dystopia down.” Y2K is a really good way to look at a crisis; the context is different every time, but human nature remains the same. We repeat the same fears and anxieties and hopes.

Becker: It’s a balancing of what Grace Hopper, the early computer programmer, says in our film, that we’ve always been afraid of new technology that we can’t fully comprehend yet. There is something in the last 10 to 15 years that feels especially dystopian to me, culminating in a recent swelling of artificial intelligence capabilities that does really worry me.

Filmmaker: Maybe those ’90s movies like The Net and Johnny Mnemonic were right after all.

McDonald: They were totally right! The first line of Johnny Mnemonic is something like, “It’s 2021. Corporations rule the world.” [laughs]