Back to selection

Back to selection

“Retain the Depth and the Breadth of This Community”: Editor Nathan Punwar on Sugarcane

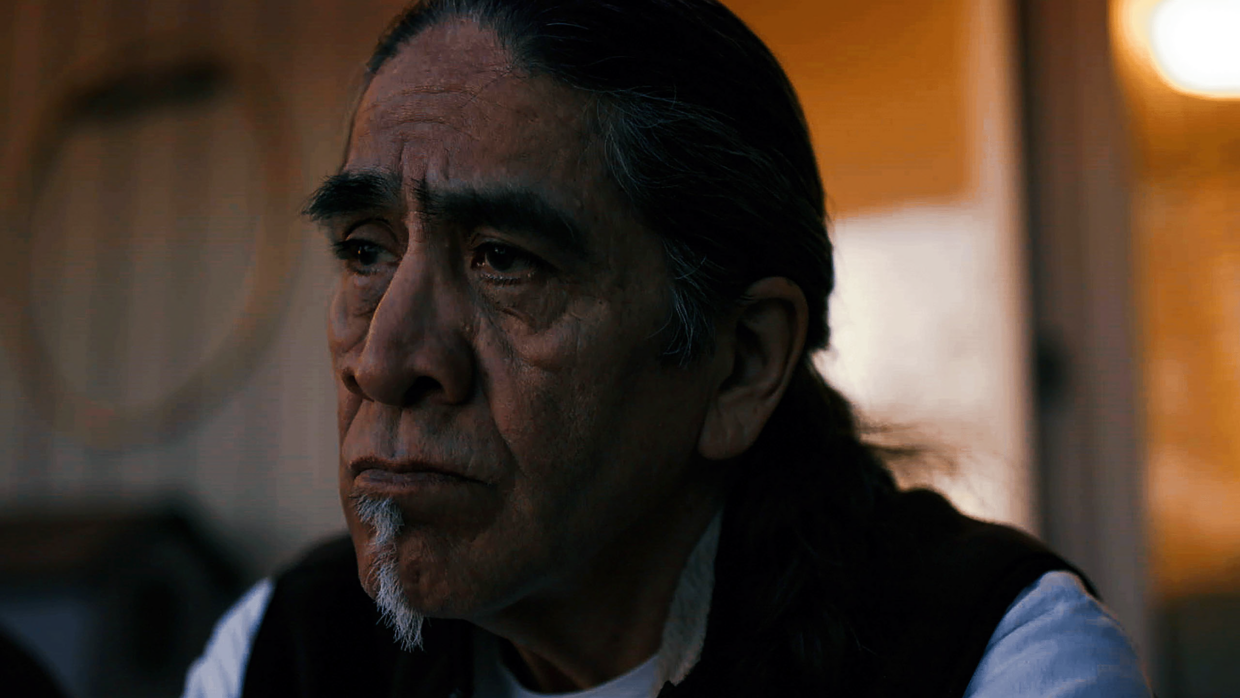

Still from Sugarcane. Courtesy of Sundance Institute. | Photo by Emily Kassie

Still from Sugarcane. Courtesy of Sundance Institute. | Photo by Emily Kassie Tackling a timely but under-discussed contemporary issue in both the United States and Canada, journalists Julian Brave NoiseCat and Emily Kassie investigate a string of abuses and missing persons cases at an indigenous residential school in Sugarcane. The film, naturally, spends a great deal of time with indigenous peoples, and the filmmakers sought to maintain evidence of the deep culture and community of their subjects. Below, editor Nathan Punwar explains how they reconciled that goal with the need to keep the film moving.

See all responses to our annual Sundance editor questionnaire here.

Filmmaker: How and why did you wind up being the editor of your film? What were the factors and attributes that led to your being hired for this job?

Punwar: I spoke with the directors, Julian and Emily, several times and connected strongly with their clear desire to tell this story from the present day, fully immersing the audience in this place and following subjects on personal journeys to connect to the past. I was eager to work in this style, different from any film I’d cut before, and I approached my collaboration with an openness to listen and react to the ways the directors hoped to convey the many ideas within the film. I’m sure there was more to it, but this laid the foundation for our conversations, which flowed naturally from there.

Filmmaker: In terms of advancing your film from its earliest assembly to your final cut, what were your goals as an editor? What elements of the film did you want to enhance, or preserve, or tease out or totally reshape?

Punwar: One of our main goals throughout the edit process was to retain the depth and the breadth of this community and its culture, which Julian and Emily painstakingly documented, knowing that not every aspect would be able to have screen time. Our challenge in the edit was to find ways to condense the multitude of details and a rich history, nod to them and not always fully explain them, while making sure their inclusion didn’t confuse or distract from the story.

Filmmaker: How did you achieve these goals? What types of editing techniques, or processes, or feedback screenings allowed this work to occur?

Punwar: It took many rounds of taking scenes or parts of scenes out, putting them back in, and seeing how storylines and emotional arcs were affected by their presence or absence. Sometimes this meant removing an entire storyline, then assessing how the remaining film felt, and often re-cutting those scenes in order to try it out in a new configuration. In this way, we were constantly testing how much information and emotion the film could contain with clarity.

Filmmaker: As an editor, how did you come up in the business, and what influences have affected your work?

Punwar: I started as an in-house editor at a record company cutting short-form pieces and promos. At the end of my time there, I cut an hour-long archival documentary. From that point on, I sought documentary editing work and also took on music videos and commercial projects. Most of the editors I sat with along the way gave me strategies I now pull from on every film I cut. I looked up to editors who were always seeking new challenges, and I still try to follow that path myself.

Filmmaker: What editing system did you use, and why?

Punwar: We used Adobe Premiere. I’m mostly software agnostic. Emily wanted to do some selecting and cutting at times and was more familiar with it. We used the Frame.io integration extensively in the early stages of marking up the hundreds of hours of raw footage and continued to refer back to those notations all the way up through the final days of editing.

Filmmaker: What was the most difficult scene to cut and why? And how did you do it?

Punwar: One of the first scenes we cut was also one of the last to be finished. In it, Julian meets Charlene, an elder relative, at a barn on the site of the former school, where she calls him to listen and bring light to these stories. This moment carried significance for the directors, as it shifted the trajectory of their film, prompting Julian to become both director and subject. They also experienced it as a spiritual encounter with the spirits of the children who once inhabited that space. To convey both the intangible and the reflexive required a balance of comprehension and mystery, emotion and restraint. We cut it many times, pushing it toward either end of those spectrums, while also seeking the right placement within the structure, so that it would land.

Filmmaker: Finally, now that the process is over, what new meanings has the film taken on for you? What did you discover in the footage that you might not have seen initially, and how does your final understanding of the film differ from the understanding that you began with?

Punwar: While I immediately recognized the strength of the film’s main subjects and their journeys, it wasn’t until later in the process that I understood better the power of living testimony given by characters we meet for one scene and never see again in the film. These testimonies add up to an undeniable collection of evidence pointing to the painful truths at the center of this history. They emerged as some of the most powerful moments and tied the specificity of our main subjects’ stories to the collective experience in a profound way.