Back to selection

Back to selection

17 Soundstages and 750 Crew Members: DP Alice Brooks on Wicked

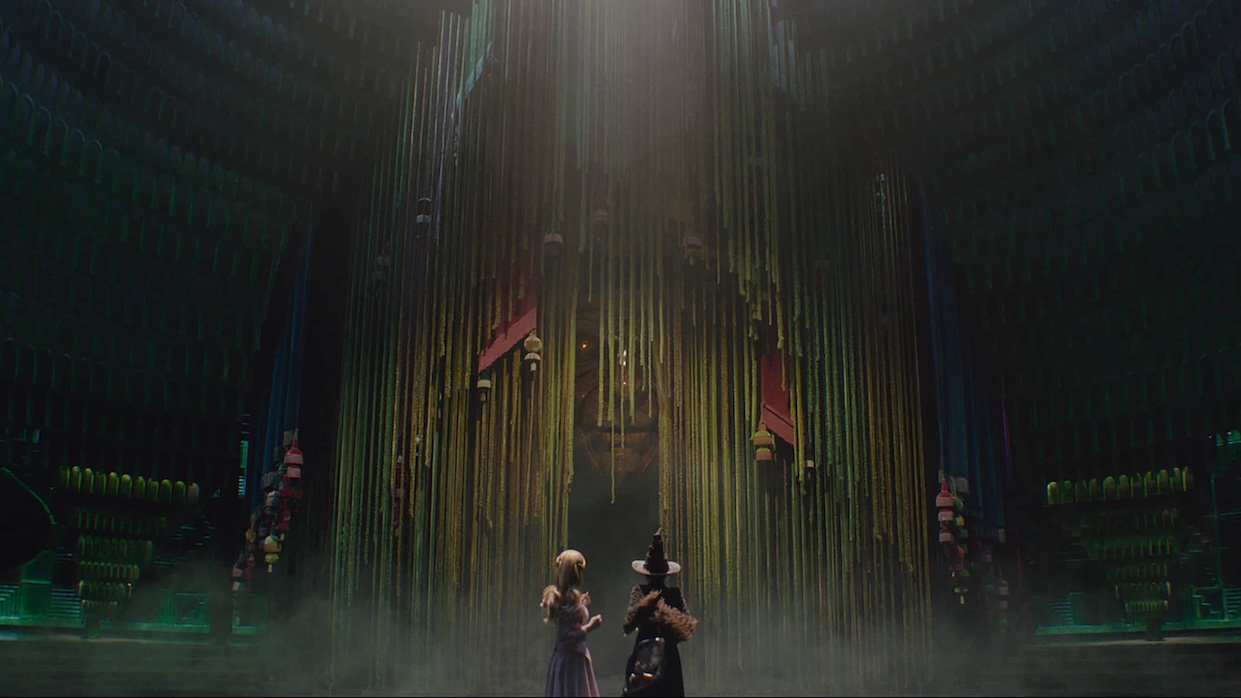

Ariana Grande and Cynthia Erivo in Wicked

Ariana Grande and Cynthia Erivo in Wicked Drawing on a huge fanbase, the screen adaptation of Wicked has helped revitalize the year-end theatrical box office. Director Jon M. Chu’s Wicked builds on its Broadway pedigree by casting Cynthia Erivo and Ariana Grande as Elphaba and Galinda/Glinda, frenemies who are summoned to the Emerald City by the Wizard of Oz (Jeff Goldblum).

Wicked unfolds on a massive scale that can feel overwhelming. Nine million tulips were planted for an exterior scene. One set encompassed two soundstages with the wall between them removed. The score by Stephen Schwartz and John Powell was performed by an eighty-member orchestra. Finding intimate, natural moments became key to the film’s success. To that end, most of the songs were performed live. Large scale practical sets became a playground to make a film that is vast in scale but feels handmade, ending at the play’s halfway point with Elphaba’s anthem “Defying Gravity.” The second part will be released in 2025.

Cinematographer Alice Brooks has been working with Chu since their days at USC Film School. She shot his musical In the Heights, which she followed with tick, tick…BOOM!, about musician and composer Jonathan Larson. Brooks brought Wicked to the 32nd EnergaCAMERIMAGE, where she participated in a panel with production designer Nathan Crowley and in a post-screening Q&A. We met at the Hotel Bulwar in Toruń.

Filmmaker: In a film this large, how do you keep your personal vision?

Alice Brooks: It’s really two movies, right? Sometimes we’re shooting scene 23 on movie one, and the next day we’re on movie two on scene 108. It’s about our knowing where you are in the story and what the emotional cues are.

Jon and I create a roadmap, one-word descriptions for each scene. If I get lost—like if I look at a scene and the lighting’s not working, or the camera’s not working—I open my script and see the emotional intent for the scene. It triggers me to remember where we should be and why. I’m able to refocus my vision.

Filmmaker: What is your process like with Chu?

Brooks: I’ve known Jon for almost 25 years. We have a different viewfinder on life, but we’re trying to tell the same story. Also, you surround yourself with supportive people. I’ve never made a movie of this scale before, or in the UK. It was terrifying at first. But my crew was amazing. I had never worked with any of them before. We started on our smallest set and ended on our biggest set. Over and over the course of 155 days, you learn to trust the people around you.

We also have a process with Myron Kerstein, our editor on this and In the Heights. I call him every day after work and we go over the dailies. Jon doesn’t like to call “cut” because then hair, makeup, everyone else jumps in and you’ve lost 20 minutes. So we do these really long takes. Myron’s in the screening room, everything’s loaded, and he just sits and watches dailies seven hours a day. I call him every day after work and he says things like, “I think this is working,” or, “I think you could do this better.” Completely honest feedback.

Filmmaker: I’m imagining this very regimented shoot where everything’s worked out to the smallest detail. Can it feel like you’re copying a shot list?

Brooks: Jon and I make a storyboard before we do a shot list. If the scene’s very complex, then visual effects will do some previs. We all understand what everyone has to get. We create a shot list, but when we get to the set we don’t look at it. As Jon puts it, every movie keeps being made over and over. You make it during development, you make it during prep, then you shoot it and that’s a new movie that’s being made. In editorial and visual effects, it’s another movie. You go into sound and a whole new movie comes to life in that period. In all these stages, you have to forget what you’ve learned before and be open to something new being born.

Filmmaker: Do you have any wiggle room if you get stuck?

Brooks: The best advice I ever got was from Woody Omens, ASC, my cinematography teacher in college. We still talk on the phone a couple of times a week. He’s 89. He said, “Light a set, walk around the room after rehearsal and turn off at least one light.” It’s the best advice because one, you don’t need as many lights as you think you do. And two, it pushes you just a little bit. He also said to change or swing a lens, one lens wider, one lens tighter. Whenever I look at something and it just feels off, I think of those two things.

Filmmaker: Talk about adjusting from a relatively small production like tick, tick…BOOM! to this.

Brooks: It was a huge adjustment. I moved my whole family to London for 14 months. We uprooted our lives. I had seven days off in eight-and-a-half months. On weekends I would prelight. It was my quiet time, working with only 12 crew members instead of 750. We had 17 soundstages on this movie. The sets went from fire lane to fire lane and from floor to the ceiling. We had five backlot sets: Munchkinland, the train station, the cliff, Shiz [the school Elphaba and Galinda attend] and the Emerald City. The latter two were the size of four American football fields. Jon wanted real, tangible sets. We tried working with a Volume very early on, but Jon likes to be able to move 360 degrees. So, everything needs to be dressed 360 degrees, and I need to light 360 degrees. Because we’re working with very long, extended shots with the camera moving in figure-eights, we ended up doing 6,000 lighting cues. When you have real sets, you have endless possibilities. Whereas if you’re sitting on a blue screen stage, there’s nothing to inspire you.

Filmmaker: How did you decide on your camera package?

Brooks: I owe almost every part of my career to Panavision. My first call was to Dan Sasaki. We talked about the feeling and mood we were after. Dan had an idea for a new lens series and asked me if I wanted to be part of creating them with him. They are now called the Ultra Panatar II but at the time we called them the Unlimiteds after a lyric in Wicked.

One day I was at Panavision doing an early camera test. We lined up every single body, cameras that weren’t out yet, everything. I threw the lens on the Alexa 65, even though it didn’t cover the sensor. Jon and I projected the tests at Company 3. The second we saw the Alexa 65 footage, we said, “We’re shooting the movie on this camera.”

The time frame was tight to build the new lenses for the Alexa 65. When we started the first week, we didn’t have all of our lenses. Day by day more would come in. We selected amber for the lens flare color. I told Dan I wanted this effervescent, romantic quality, and it’s built into the lenses. He asked what stop I wanted to shoot at, and made all the lenses open to T 2.8. When I needed one, he even built me a 29mm lens in about a week.

Filmmaker: At a Q&A you mentioned shooting with iPhones.

Brooks: Jon M. Chu and [choreographer] Christopher Scott and I worked on a Hulu show called The Legion of Extraordinary Dancers about 15 years ago. It was this playground for us to try new things, and to make mistakes. We learned how to move bodies through space, how gravity works. During rehearsals we shoot videos from our own perspectives, without anyone’s input. Sometimes it’s just me and the choreography team. Chris Scott is there most of the time, and Jon is in and out like I am. For Wicked, I brought our Steadicam operator Karsten Jacobsen in. He had 10 weeks to study the choreography, shooting his own videos as well. We Airdrop the footage to Jon, who starts cutting them together in Final Cut Pro. Then we all sit down and start to think of other shots, or what is missing, or whether this should be a crane move, or do we need to move at all. There is so much quiet and stillness in this movie. Jon kept saying to lean into the moments where the camera doesn’t move or the sound drops out. It is in the silence that this movie actually exists.

Filmmaker: You have an incredibly intricate shot in the school library: stacks are spinning in circles, the camera’s moving, and you push in to Jonathan Bailey [Fiyero] singing on a cart.

Brooks: We found the shot on an iPhone. But when you put the Alexa 65 on a crane in that space with a huge M7 head, it becomes very difficult. Plus there are three spinning ladders, so you have to time everything to be able to pull back the camera so that it appears center and not get hit by a ladder. Sometimes we’re spinning the head 360 degrees, so you don’t know which way’s up.

In one shot while we’re pulling back and spinning, a parkour dancer flips over the camera. Chris Scott came up to me and said we had four takes, because the parkour can only do it four times or he’ll hurt himself. Take one, we miss it. Take two, miss. Take three, another miss. On take four we get it.

Filmmaker: How do you respond to that pressure?

Brooks: That’s what making movies is, right? Constant challenges that are presented to you. You try to rise to the challenge. Sometimes it works, sometimes it doesn’t, and in the next minute there’s a new challenge. It’s our job to figure things out. And if you can’t, how can we make it work another way? If we hadn’t gotten the shot, what is the alternative? How can we do it differently? It’s not really pressure, it’s just the way life is. At least on the movies I work on.

Filmmaker: I was impressed by a two shot of Elphaba and Madame Morrible (Michelle Yeoh) descending a spiral staircase. At the end the camera spins around to a perfect close-up of Yeoh.

Brooks: That was a Steadicam. The space was too tight for a crane. Karsten backed down the stairs before them. He’s a remarkable operator, never loses the horizon. He’s so solid at times I asked him to be a little looser because everything was so perfect. The camera never floats when he is operating.

Filmmaker: Did he do the shot in the Ozdust Ballroom where Galinda and Elphaba hug for the first time? I remember a tear coming down Elphaba’s face.

Brooks: That was a ten-minute take. Jon wanted Cynthia to walk into the Ozdust Ballroom and feel the space for the first time without a camera rehearsal. Karsten has to pull her down the stairs and do a 360-degree shot that runs ten minutes to the end of the scene. Our focus puller is next to the camera, going around for ten minutes without losing his balance or getting dizzy. There are 500 lighting cues in that shot, because sometimes Cynthia’s wearing a hat and sometimes she’s not. We’re in a club with lights moving. We can’t have camera shadows, so the lights are dancing while Karsten is dancing while Cynthia’s performing. Sometimes we slow down and don’t move. The camera looks completely locked off, but it’s all part of the Steadicam shot. It wasn’t in the script that Cynthia cries, that a tear drops down her cheek and Ariana wipes it away. That’s why everyone has to be 100 percent prepared for magical, unplanned moments like these. Then we went back and shot Ariana’s side, which is also ten minutes of circling around. We got a medium shot of both of them, head-to-toe shots, close-ups of the principals, the background cast, all the rest.

Filmmaker: Did Erivo have to cry in every take?

Brooks: I don’t know how she did it, but at the end of the day, she just sort of dropped to the ground, completely drained emotionally. I don’t know how an actress can go to that place over and over and over again. We still had more stuff to shoot in that sequence, but Jon promised we were done being close to her, that we would only see her from afar. She could put whatever it took to get her there to bed.