Back to selection

Back to selection

Shutter Angles

Conversations with DPs, directors and below-the-line crew by Matt Mulcahey

“1.66 Just Felt Good”: DP Jarin Blaschke on Nosferatu

Nosferatu

Nosferatu Over the course of his four feature films, Robert Eggers has gained a reputation as a filmmaker obsessed with meticulous period accuracy. After listening to Jarin Blaschke talk about moon size as a mathematical equation, it’s easy to see why Eggers has enjoyed working with the equally meticulous cinematographer for almost two decades.

“I’m kind of a stickler about how big a moon is when a CG moon is in frame,” said Blaschke. “It needs to be 1/80th the width of the screen, because the moon is a half a degree wide and our lens takes in 40 degrees. So, that’s pretty simple math. Moons in movies are usually way too big, and that’s why they sort of feel off.”

The pair’s latest effort, an early-1800s set update of the silent vampire classic Nosferatu, provides ample opportunity for rigorous period recreation and mathematical lunar placement. With Nosferatu now available on VOD and physical media, Blaschke spoke to Filmmaker about his Oscar-nominated work on the movie.

Filmmaker: Robert staged a production of Nosferatu in high school, so it’s obviously a story that has resonated with him for a long time. You’ve been working with Robert for years. When did he first throw out the idea to you that Nosferatu was something he was interested in making?

Blaschke: I met Rob, like, 17 years ago. I went to New Hampshire to shoot a short film for him, and we went to his mom’s house and met his brothers. While I was there, I saw a picture of Rob from the play as Nosferatu on the refrigerator. That’s the first time I heard about his connection to it.

Filmmaker: Your version is inspired by the F.W. Murnau silent film, but the story of Nosferatu is really just the story of Dracula. So, in addition to the Murnau film and the Werner Herzog remake from the 1970s, you’ve also got a century of Dracula reincarnations as well. How do you approach that history? Do you try to watch everything? Do you watch nothing?

Blaschke: I tend to be on the lighter side [of revisiting past versions]. Rob is constantly watching films, from comic book movies to the most obscure Belarusian misery porn. He always curates something for me. He’ll send me a list of 20 or 30 movies and puts them in order of relevance. I usually get through about five. He always rips me. He’s like, “Oh yeah, Jarin watches three of them.” [laughs] He’ll also curate sequences for me to point to what I’m supposed to be looking at.

Filmmaker: What was on Robert’s curated list for Nosferatu and which five did you make it through?

Blaschke: I can’t remember the five. I do remember The Innocents. That was probably the most meaningful one. He showed it to me for the blocking.

Filmmaker: I’m assuming you went on some of the scouting trips to Romania and Germany?

Blaschke: Yeah, we had an early trip in 2021. We went to Lübeck, Germany [where some scenes from Murnau’s Nosferatu were filmed]. The trip was mostly about architecture, but it was great to hang out with everybody and see if there were any locations we could use. The answer was kind of “no,” because even if you have these amazing buildings, you’ll never get a whole city street of them. Even if you got four in a row, one of the buildings will have a Starbucks on the ground floor. We also went to Romania and looked at these living museums to see what the villages would have been like. We looked at Hunedoara Castle, which Rob thinks was the inspiration for the castle in Bram Stoker’s novel. I think it broke Rob’s heart because he went there years ago, like 2016, when the movie was with a different studio. Then we went during our scout and the interior had been scrubbed totally clean—all the patina was gone for the tourists. In the end it came down to shooting in the Czech Republic, which worked for 95% of what we needed. The rest is movie magic.

Filmmaker: The movie is mostly studio-based?

Blaschke: Yeah. I don’t know the exact figure, but I would guess something like 80 percent sets.

Filmmaker: Your first feature with Robert—The Witch—was digital, but since then your films together have all been shot on film. Did you test stocks for Nosferatu?

Blaschke: On The Northman I used every stock that Kodak has, because they all had different purposes depending on what kind of scene it was. So, I was already very familiar with all of them. In the end, the utilitarian choice was 5219 because I wanted to bring back lighting by real fire and real candles. Then I just decided to do the whole movie with the same stock for consistency.

Filmmaker: Did you use the Kodak Vision3 5219 500T?

Blaschke: Yeah, because we had low light work. I rated it at 250 because I think it gives you a very full scale, well separated shadows and much more to work with when you have a film that dwells so much in the shadows.

Filmmaker: Does that mean you’re basically overexposing by a stop if you’re rating at 250?

Blaschke: I don’t think you are. I think at 500 you’re underexposing, but that’s my opinion. It’s just about where you want your image to lie on the curve, and that’s how you decide how to expose it. I don’t think it’s as simple as over and under. It’s about the look you want and how you bake that into your process.

Filmmaker: Did you process normal or did you push?

Blaschke: I did push it a half stop. I tested a full stop, but it got a little too severe as far as microcontrast and texture and edges. I still wanted a smooth, lush palette overall. [A half stop] was as far as I could go before it lost that creaminess.

Filmmaker: In terms of where the blacks live, it felt like you were using a lot of haze, which can bring the blacks up. I’m thinking specifically of the solicitor’s office.

Blaschke: Oh yeah, it’s every scene—the interior at the inn, definitely von Franz’s attic, you name it. But when they walk into a foreground two shot, the foreground is a nice black against that. All the haze is probably another argument to expose it at 250.

Filmmaker: Is there a trick to getting the haze right?

Blaschke: Well, the whole time between takes you’re giving signals for more or less, or to stop. You’re opening doors if it gets to be too much. Rob would tell you that in a few scenes we went almost too smoky. Then he’s not seeing his sets. It’s this delicate thing of wanting atmosphere, but also a lot of work went into [everything in the shot] from the casting of extras to the sets to the props. So, it’s a fine balance.

Filmmaker: Is everything single camera?

Blaschke: Yep. It’s the only way to shoot as far as I’m concerned. This ain’t television and it ain’t sports. [laughs]

Filmmaker: It’s not the norm anymore to shoot single camera.

Blaschke: I know, I’m just playing with you. I mean, Kurosawa used multiple cameras. But we’re just too hyper-focused to add another camera. If you do, then you have to use a longer lens, and Rob and I don’t know how to really shoot with the longer lenses. Everything’s just on a 35mm, then you move on to the other things you’ve got to do.

Filmmaker: What was your lens package like?

Blaschke: With The Northman, we had a few different film stocks but pretty much one lens. This time we brought in some more flavors. The baseline was my favorite lenses for the last several years—basically since The Lighthouse—which are these Baltar lenses from Bausch + Lomb, who don’t even make camera lenses anymore. They designed them in the 1930s. I came across them at Panavision while testing for The Lighthouse. I tested them against Cookes and their Super Speeds and everything else and fell in love with them. I shot The Lighthouse with them and the highlights kind of glow, and the skin has this luminous quality that offsets the severe orthochromatic look in an interesting way. With The Northman, I was obsessed with shooting the cleanest movie possible, so that was very modern in its lens choices. For Nosferatu it was back to the Baltars, which I’ve used on some commercials here and there as well. It’s my favorite double-gauss lens. So, that was our main set, and then Panavision made some high-speed lenses for us so we could shoot under candlelight, because I was determined to shoot by real candlelight only. I didn’t want to use anything electric like we had done on The Northman. Those high-speed lenses allowed for that.

Filmmaker: How fast were those special-made lenses?

Blaschke: There are limitations, because there’s a spinning mirror in the camera. So, you can’t get the back of the lens really close to the film, but Dan Sasaki at Panavision wrung out everything he could. We had a 40mm lens that was a T0.9. With the wider lenses it’s a little harder. So, the 35mm—we shoot 90% of our work on the 35—was a T1.1. We also used a Dagor lens for some of the Count Orlok stuff. It was used for things like the carriage scene and then the scenes that have that kind of magical ambiguity of, “Are you in a dream or is this real?”

Filmmaker: I don’t know that one. What is a Dagor?

Blaschke: View camera still photographers know what a Dagor is, but it’s not used in filmmaking. I asked about it just because if you give me an inch I’ll ask for the world. So, I asked Dan about that, then I asked about another kind of lens called a Heliar. He made both of them for us. The Heliar was famous for being a portrait lens. There’s this legend that the Emperor of Japan would not have his picture taken on anything other than a Heliar. So, Dan made that, and it was actually too clean and too neutral. It’s a beautiful lens and I’ll use it one day for something—unless they’ve dismantled it. The Dagor is interesting because that is a lens design known for landscapes. There’s not a lot of air-to-glass surfaces in that lens. The more transitions from glass to air in your lens, the more light has a chance to bounce around, so the lower the contrast becomes. The Dagor was an attempt to get a high contrast lens in like the 1890s, before there were lens coatings. If you use our Dagor at a certain stop, it has this beautiful glow and things kind of fall out of focus in this really misty way that was like nothing else I’d ever seen. It’s almost like a pictorialist look, even though it’s on a lens that’s designed to be sharp. Then, if you stop down, it gets super sharp again.

Filmmaker: So, there’s a sweet spot?

Blaschke: It depends on what kind of look you want. It’s like what we talked about before in terms of exposing your film. If you expose it one way, it looks like this. If you expose it another way, it looks like that. It’s not a one-trick pony.

Filmmaker: Let’s talk about choosing your aspect ratio. The Northman was 2.0. The Lighthouse was something unusual.

Blaschke: That was 1.19.

Filmmaker: And then The Witch was 1.66. How did you end up back at 1.66 for this one? The original silent Nosferatu is obviously 1.33.

Blaschke: This is its own movie, so we’re not necessarily trying to [imitate the original film]. I mean, 1.66 just felt good. [laughs] It felt right. You’re weighing all these other options in your mind, and we kept coming back to 1.66. Early on 1.33 was certainly considered but I think this movie has [a degree of] scope and scale. There are some landscapes and there are certainly crowd scenes and it’s an ensemble piece where you’re going to have four people in a scene. A lot of times we have two foreground characters talking to two background characters and then you have a reverse tableau of the same thing. It’s just horizontal enough that I think it warranted 1.66. To me, 1.85 feels sort of like it’s neither here nor there.

Filmmaker: Let’s get into some specific scenes, starting with the opening sequence. It’s not quite black and white. There’s a blueish tint.

Blaschke: Yeah, it’s a little blue. It was shot on color film. I matched all those scenes [with that blueish hue] to each other. In retrospect, maybe I should have cheated some of them a little less blue if they were coming after a candlelight scene. I can tell you they’re all exactly the same color, but they feel different depending on the context. That was a lesson for me. The lighting is just naked HMIs or daylight LEDs, then you have a tungsten film stock. All the moonlight is shot through a filter on the camera that’s similar to the filter I used on The Lighthouse. It completely eliminates red and orange light and most of the yellow. So, the red layer on the film has like zero information, and you’re giving more exposure to blue and a little bit to green. We’d done that on The Northman as well. For Nosferatu, I was going to try to restore just a little bit of that red information, but we couldn’t get a new filter made in time to test and shoot. It was easiest to create that look with a filter on the camera, but I also found a gel by Rosco that I think was called Summer Blue that had a pretty close spectral response to the filter. Sometimes I put that on the windows if it was a night interior, or if I had to mix light with torches I would put that gel on the HMIs. That’s the least desirable way but that’s the only way you can do it when you want to affect your moonlight, but you want the firelight to remain intact. So, on set, you have this ridiculously crazy cyan light next to your torch light, and then in the grade you just grab the blue layer and desaturate just that layer.

Filmmaker: In that opening sequence, there’s a shot where Ellen [Lily-Rose Depp] goes to the window and Orlok’s shadow appears and disappears as the curtain sways. How did you do that?

Blaschke: Almost all of our shadow work was on set and real, but there are two exceptions in the whole movie and that’s one of them.

Filmmaker: The symmetrical wide shot in that opening sequence where Ellen runs out of the house feels like day for night.

Blaschke: That might be our only day for night in the whole movie. The problem is that in the Czech Republic, you don’t get sunny days, and, in my opinion, you need a sunny day to shoot day for night. I don’t think overcast works at all. For [day for night] moonlight work it needs to be hard light, just because it’s so dim that it needs like a hard edge to define everything. You need a certain level of contrast. So, day for night is trickier in Europe and certainly you can forget it if you’re shooting in England.

Filmmaker: How do you achieve the cool tone of your daylight exteriors? Are you just shooting tungsten film in daylight without an 85 filter to correct?

Blaschke: In earlier scenes I used an 81EF filter, which is half correction, and then later I just didn’t use anything. We’re partially correcting it in the grade, but at least the baseline is very blue-heavy. That reads differently on the skin than if you shot it with a full correction filter and then print it back to blue.

Filmmaker: For the scene where Nicholas Hoult’s Thomas Hutter first meets Orlok [played by Bill Skarsgård] in his dining room, is that entirely lit by the practical fire behind them?

Blaschke: Yep. That’s it. What you see is what you get. Our gaffer tried to put something over the table so you could see the feast. I get that as far as information, but I like stuff that looks natural. So, I try to do a “curated natural.”

Filmmaker: How did you approach lighting for your day interiors, like the solicitor’s office? It feels like a single source motivated from the windows without fill.

Blaschke: Actually, I am using fill, but I put it at a very subtle level. First, you get your quantity figured out. You say, “Okay, I need a 2.8,” which means facing the window I’m going to give it maybe a 4 depending on what the scene calls for. Now we’ve got our base, and then it’s like, “That wall back there is just too lit,” because maybe we have an actor that needs to be set against a dark part of the wall. So, I’m going in and selectively placing nets. Usually, I’ll put the 4’ x 4’ nets or 8’ x 8’ nets outside the window and not on set just to keep the set clear, but opposite the area I want to affect because the window acts like a very soft pinhole. Then it’s time for fill, and I like for my fill to be an extension of the key. For scenes with soft light, basically I build a cyclorama of white out the window, and we bounce into that. Inside, extending from the window I’ll have a bunch of 8’ x 8’ muslin frames and usually it’ll catch the ambient light enough to hit the level I need, but sometimes not and I’ve got to put a Joker or a Leko on set and make that bounce active. Usually, I like to just wrap it around. For example, if I have an actor next to a window I’ll put white extending from the window source to the camera so that it wraps around to the front and for this movie I’ll set that at like a minus three. Your fill is very subtle, but you still get the catch light on the dark eye from the passive white that’s behind camera.

When you have hard light that gets complicated, because I want my hard source to be as far away as possible. The sun is relatively small—it’s only a half a degree of your vision—so I’m always trying to get the light as far away as possible, but then my [passive bounce] is too weak. So, I’ll put a mirror in each window that’s reflecting a hard source that’s like across the stage somewhere, like an 18K with a spot reflector banging into that mirror.

Filmmaker: For the night exterior where Hutter meets the carriage in the woods that will take him to Orlok’s castle, what did you use for that large backlight behind him?

Blaschke: We used two hard sources, one of them as high as possible for our moonlight. Usually in movies you don’t see a very high moon. It’s usually kind of raking across. Maybe it’s just because I do this for a living, but I can usually tell it was just like, “We only had a stand or we were limited with our lifts and we did our best.” So, moonlight is usually horizontal in movies, which I find kind of annoying. My experience of moonlight is almost like this high noon [position], and it just feels more magical to me that way. Everything is super clear, but just dim. That’s my memory of growing up in the desert and going for moonlight walks when I was a kid.

Filmmaker: I like that slow 180-degree pan from Hutter to the open door of the carriage.

Blaschke: Yeah, we’ve done that a few times. We did that in The Northman too. I guess we have our thing. [laughs]

Filmmaker: There’s a shot where Hutter walks toward the carriage and gets in. At some point he almost starts to float along with the camera. Is he stepping onto a dolly at some point?

Blaschke: Yeah, that was pretty lo-fi. It’s a big dolly, like a Fisher 10 or something, with a hydraulic arm. Instead of putting a camera on the arm, you put a platform on there and the actor just steps on this platform, then he’s riding on a dolly that’s just below frame.

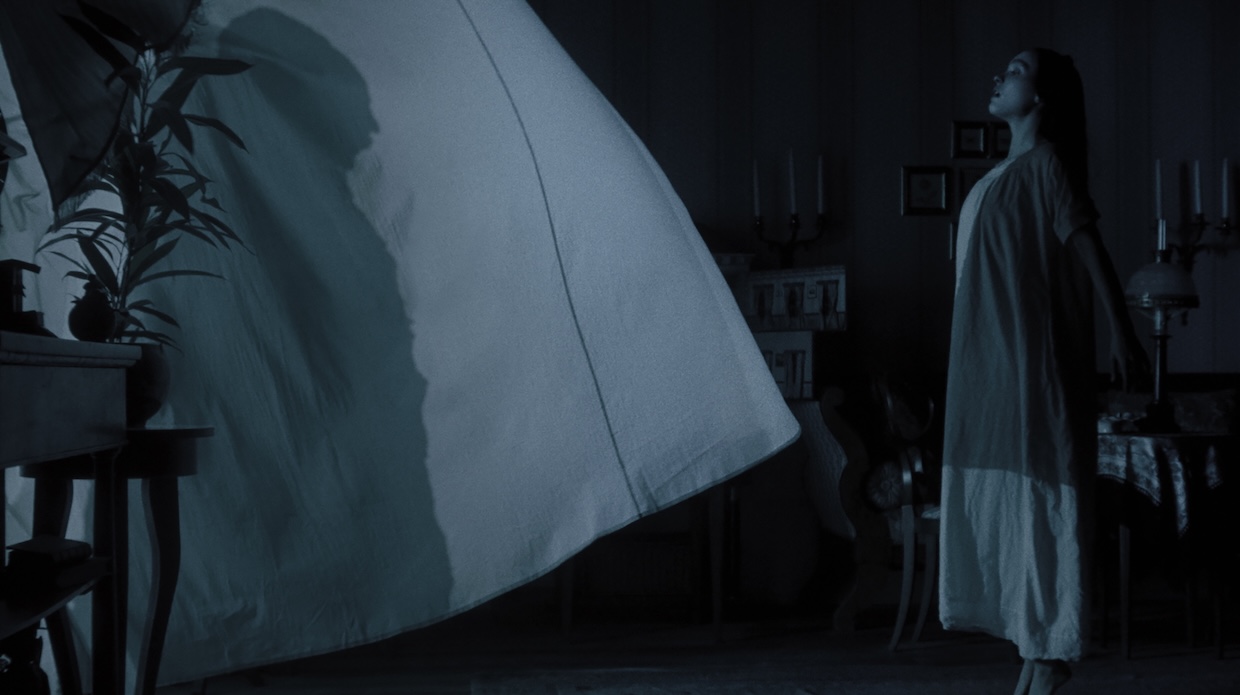

Filmmaker: One of the more memorable shots in the original Nosferatu is Orlok’s shadow reaching toward Ellen’s bedroom door. You do a more complicated version of that, where you’re panning around the downstairs of her home as the shadow moves toward her room.

Blaschke: That’s all Bill’s actual shadow, then we put a wipe as we go from the parlor to the staircase because it’s a difference position for Bill. But for the section in the parlor, Bill could literally walk from one window to the next. For each window we set an optimum distance to get [the shadow] the right size, but that was actually real. Once it was lit it was pretty straightforward.