Back to selection

Back to selection

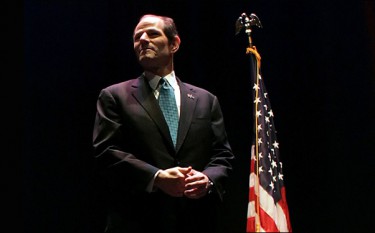

@IDFA: “CLIENT 9,” “PROSECUTOR”

In straightforward PBS style, Canadian Barry Stevens’s Prosecutor follows Luis Moreno-Ocampo, Chief Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court (ICC), and an unconventional and charismatic Argentinean with a colorful past. Moreno-Ocampo’s resume runs the gamut from bringing to justice the war criminals of his homeland in the 1980s and teaching at Harvard to serving as soccer star Maradona’s lawyer and hosting a Judge Judy-type TV show. Five years on the job and still struggling to reel in big Sudanese fish Omar Al-Bashir, Moreno-Ocampo is finally bringing his first case — the prosecution of a Congolese military leader charged with conscripting child soliders — to trial. Yet what’s most fascinating about Prosecutor is that the lead hero, who favors white suits, has less in common with the wise old Nuremberg prosecutor who visits his office to express his support than he does with a onetime Attorney General starring in another doc also screening here at IDFA, Client 9: The Rise and Fall of Eliot Spitzer (pictured above). While Moreno-Campo is probably more likely to be found winding down with Law and Order episodes on videotape (glimpsed in his apartment in The Hague) than he is dialing for hookers, he’d do even better to catch Gibney’s film in his spare time. The fate of New York’s steamroller governor could serve as a crucial cautionary tale about the price of moral high ground hubris.

What Client 9 makes perfectly clear is that love him or hate him (and I’m more of the “hang the hypocrite” mindset) the personality traits that made Spitzer such an effective A.G. were the same ones that alienated Albany and the lawmakers he needed most to function as a game-changing governor. As Moreno-Campo himself allows in Prosecutor, because he isn’t working within a state he has to build the nations around him. In essence, he must painstakingly form coalitions, which requires compromise and a political savvy he doesn’t possess and doesn’t appear motivated to acquire. Indeed, the prosecutor seems to view his job as being above politics — and peacemaking, for that matter. (Which isn’t to say he’s not media savvy. Much to the probable chagrin of his advisers he signals the ICC’s neutrality by letting drop during a BBC interview that he’s looking into possible war crimes committed in Gaza.) “Can I delete this ‘peace and justice working together?’” Moreno-Ocampo asks a colleague as he goes over his UN Security Council address. Peace, after all, is not the ICC’s mandate. But his belief that he can dodge politics and “change behavior without changing the regime,” as he puts it, is naïve at best. More often it’s a recipe for disaster and long, drawn out stalemates with serial-killing heads of state while untold numbers of lives are lost.

Fortunately for Spitzer his inflexibility and my-way-or-the-highway maneuvering only brought himself (and let others) down. But Moreno-Ocampo’s intransigence, his unwavering faith that what worked in Argentina — or even at Nuremberg — will work for the world is downright lethal. (For proof look no further than another doc, Lucy Bailey and Andrew Thompson’s terrifying Mugabe and The White African, which shows the flipside — those promised justice by the ICC and the violence intensified by an institution that places ideology before basic security. Spitzer’s Achilles heel was his assumption that he could manhandle State senators and assemblymen the same way he had Wall Street financiers, which is not unlike how Moreno-Ocampo insists on treating dictators with international muscle in the same manner he took on powerless war criminals in Argentina. As the elderly prosecutor notes, he didn’t have to call a single witness during the Nuremberg proceedings. The bombastic SS men on trial had already been defused.

For the former governor the consequences were infuriating. By alienating the legislative body he desperately needed to repair a dysfunctional system, he drove lawmakers to sympathize with his Wall Street enemies. (Many, in fact, were already in cahoots with them in the first place!) Likewise, Moreno-Ocampo is a thorn in the side of not just Africa’s murderous leaders but of their supporters like China and Russia. Not to mention that the U.S. also doesn’t recognize the ICC. Instead of wooing the members of the U.N. he’s taken a page straight from the Spitzer playbook, trying to make nice by going around them while at times showing an outright condescension and contempt that can only make things worse for those on the actual battleground. (When the ICC finally does get an arrest warrant for Al-Bashir the dictator responds by simply kicking out foreign aid groups.) There’s a scene towards the end of Prosecutor, in which Sudan’s ambassador gives an outraged speech directed at Moreno-Ocampo, who saunters directly to his side at the podium, daringly glaring at him the whole time. The audience I saw the film with immediately erupted in heartfelt applause. It’s a powerful image. And one which makes us forget that pissing matches between baddies and bumbling cowboys from foreign lands hell bent on bringing Western rule of law to unstable regions always end in shoot ‘em ups — both parties covered in blood not their own.