Back to selection

Back to selection

Criterion: America Lost and Found: The BBS Story

In a recent edition of his ongoing online column “Movie Answer Man,” Roger Ebert was faced with the following reader-submitted query: “Since good movies can now be cheaply made, why aren’t we seeing more of the kind of arthouse films that were so influential in the ’60s and ’70s?” Ebert’s response, while relatively curt, was two-fold.  “1.) It is very expensive to release, promote, and advertise any movie,” he began. Fair enough — as any independent filmmaker knows, simply getting your movie made is just one small initial hurdle…and as any viewer who watches contemporary independent films can sadly attest, the proliferation of feature films granted by the affordability of digital video production merely means that a larger number of filmmakers have an access to equipment that is wildly disproportionate with an originality of artistic vision. But the second half of Ebert’s response was more troubling: “2.) The younger generation of moviegoers has more limited tastes than the ‘movie generation’ of the ’60s and ’70s.” Ebert’s screenwriting credit on Beyond the Valley of the Dolls – more than his Pulitzer for criticism – has allowed me to begrudgingly look past his infamous, almost-quarter-century-old pan of Blue Velvet, but on this new point, I’m afraid this might be one of those instances where a difference of opinion crosses a line into becoming an error of fact. But more on that in a moment.

“1.) It is very expensive to release, promote, and advertise any movie,” he began. Fair enough — as any independent filmmaker knows, simply getting your movie made is just one small initial hurdle…and as any viewer who watches contemporary independent films can sadly attest, the proliferation of feature films granted by the affordability of digital video production merely means that a larger number of filmmakers have an access to equipment that is wildly disproportionate with an originality of artistic vision. But the second half of Ebert’s response was more troubling: “2.) The younger generation of moviegoers has more limited tastes than the ‘movie generation’ of the ’60s and ’70s.” Ebert’s screenwriting credit on Beyond the Valley of the Dolls – more than his Pulitzer for criticism – has allowed me to begrudgingly look past his infamous, almost-quarter-century-old pan of Blue Velvet, but on this new point, I’m afraid this might be one of those instances where a difference of opinion crosses a line into becoming an error of fact. But more on that in a moment.

“America Lost and Found: The BBS Story” is a new seven-film Blu-ray and DVD boxed-set from The Criterion Collection that compiles — with all of the Criterion imprint’s usual exhaustive supplementary bells-and-whistles (though, one suspects, not quite as exhaustive as it could have been had the project not originated as a “New Hollywood” set under the auspices of Sony Pictures Home Entertainment, who ultimately turned it over to Criterion’s control) — a series of films made between 1968 and 1972 by an independent production company named BBS Productions, an organization who would ultimately redefine the relationship between American independent cinema and the Hollywood studio system. Given creative control by Columbia Pictures (then in rather dire financial straits, and desperate for any solution to its box-office bloodletting) as long as the productions were budgeted at under a million dollars, BBS (an acronym standing for director Bob Rafelson, and producers Bert Schneider and Steve Blauner, although the enterprise originally began with just Rafelson and Schneider as Raybert Productions) created generation-defining mainstream smash hits (Easy Rider and Five Easy Pieces), fondly-remembered masterpieces (The Last Picture Show and The King of Marvin Gardens) and, well, a trio of ambitious albeit flawed experiments (Head, A Safe Place, and Drive, He Said). Despite the profitable nature of BBS for its corporate parent, several factors contributed to the disbandment of its relationship with Columbia — the final BBS production, the Oscar-winning documentary Hearts and Minds, was acquired for release by Warner Bros. — and the partnership’s ultimate collapse. But within the space of just a few years, BBS had inarguably altered the landscape of American filmmaking for the decades that followed.

I must confess that I wasn’t even born when the first couple BBS productions were released, and subsequently I was also obviously too young to have seen the remaining BBS titles during their initial theatrical runs. My own adolescent navigations through the hallways of studio-dominated multiplexes were spent being grateful for the occasional Lynch, Cronenberg, Scorsese, or De Palma wide release that managed to infiltrate an era of Simpson-Bruckheimer creative bankruptcy, while navigating commutes to the arthouses of major cities for Herzog, Varda, Almodovar, and Rohmer films, and waiting patiently until the distribution entities that would eventually become their own mini-majors ultimately opted to market the likes of Soderbergh, Van Sant, Lee, and Jarmusch. Which returns me to my initial objection to Ebert’s proclamation: the intelligent teenagers, twentysomethings, and thirtysomethings that I know are as knowledgeable and passionate about cinema as an art form than any generation since that so-called “movie generation” of the ’60s and ’70s, but admittedly this contemporary demographic has become so fragmented through the various means of media dissemination, social interaction, and sheer information overload that they are less readily identifiable in their tastes and viewing habits. About the only generalization one could easily make is that they’re a hell of a lot wiser, and more discriminating, in their cinephilia, than those of us who came of age in the 1980s. When a teenaged porn star sports a Godard T-shirt, and a popular satirical news website streams a comedic sketch where the entire punchline would necessitate a familiarity with the oeuvre of Lars von Trier, I think it’s safe to say that any distinctions between repertory theater, film festival, VHS, internet, and DVD/Blu-ray “generations” are rather a moot point by this stage.

I must confess that I wasn’t even born when the first couple BBS productions were released, and subsequently I was also obviously too young to have seen the remaining BBS titles during their initial theatrical runs. My own adolescent navigations through the hallways of studio-dominated multiplexes were spent being grateful for the occasional Lynch, Cronenberg, Scorsese, or De Palma wide release that managed to infiltrate an era of Simpson-Bruckheimer creative bankruptcy, while navigating commutes to the arthouses of major cities for Herzog, Varda, Almodovar, and Rohmer films, and waiting patiently until the distribution entities that would eventually become their own mini-majors ultimately opted to market the likes of Soderbergh, Van Sant, Lee, and Jarmusch. Which returns me to my initial objection to Ebert’s proclamation: the intelligent teenagers, twentysomethings, and thirtysomethings that I know are as knowledgeable and passionate about cinema as an art form than any generation since that so-called “movie generation” of the ’60s and ’70s, but admittedly this contemporary demographic has become so fragmented through the various means of media dissemination, social interaction, and sheer information overload that they are less readily identifiable in their tastes and viewing habits. About the only generalization one could easily make is that they’re a hell of a lot wiser, and more discriminating, in their cinephilia, than those of us who came of age in the 1980s. When a teenaged porn star sports a Godard T-shirt, and a popular satirical news website streams a comedic sketch where the entire punchline would necessitate a familiarity with the oeuvre of Lars von Trier, I think it’s safe to say that any distinctions between repertory theater, film festival, VHS, internet, and DVD/Blu-ray “generations” are rather a moot point by this stage.

Which brings me back to BBS, and the American cinema that followed in the wake of the success of Easy Rider in 1969. Often credited with bridging the gap between the American independent mavericks of the 1960s with the wider theatrical distribution afforded by a major studio partnership, the BBS productions inaugurated the oft-labeled “second golden age” of Hollywood filmmaking. “The Seventies,” of course, is a rather fluid and imprecise cinematic categorization: a more rigid and pessimistic definition might begin with Easy Rider in ’69, and culminate with the landscape-altering blockbuster phenomenon of Star Wars in ’77, while a more generous and expansive overview might actually reach back to Bonnie and Clyde and The Graduate in ’67, and then decline with a whimper rather than a bang throughout ’82 or ’83. But this era of American movies has actually been worshipped (indeed, almost romantically idealized) by many of the younger cineastes I’ve encountered, every bit as much as its European equivalent of the late-50s/early-60s nouvelle vague. Clearly, film buffs in their twenties have connected with something in the “New Hollywood” works of the ’70s, which has made the Criterion BBS set something of an obsessive fetish object/holiday wishlist trophy among the film geek circuit. Whether this younger generation finds comparatively few offerings among contemporary cinema to be worthy of that degree of adoration is another topic.

Easy Rider could have easily been just another low-budget biker picture for the drive-in circuit – a then-popular genre in which director/co-writer/actor Dennis Hopper, producer/co-writer/actor Peter Fonda, and actor Jack Nicholson had all toiled for Roger Corman and American International Pictures earlier in the ’60s (indeed, Nicholson was so exasperated by his lack of creative expression in these films that — by the time of Easy Rider — he was preparing to retire from acting to focus on writing and directing, additional vocations that he would indeed also perform for BBS). But Hopper and Fonda had more mythical aspirations, wishing to craft an allegorical counterculture western — not for nothing are their characters named Billy (the Kid) and Wyatt (Earp) — that would reflect a modern-day America that was rarely accurately portrayed by the studio system. The results indeed redefined Hollywood cinema of the era, culturally and financially (the film was, given its modest $350,000 budget, one of the most purely profitable productions of the decade). The film’s influence on the film industry has been so widely noted, and some of its most memorable qualities have been so widely imitated and parodied (“Born to Be Wild,” anyone?) that the actual merits of the film have tended to be neglected, or more commonly, dismissed. Easy Rider is rather widely critically berated these days (as it also was in many critical circles at the time of its release), and indeed, the film’s attempts at sociological profundity are often as clumsy and embarrassing as most dimly recalled pot-driven moments of shallow revelation, and they’re obviously long past their zeitgeist expiration date.

Easy Rider could have easily been just another low-budget biker picture for the drive-in circuit – a then-popular genre in which director/co-writer/actor Dennis Hopper, producer/co-writer/actor Peter Fonda, and actor Jack Nicholson had all toiled for Roger Corman and American International Pictures earlier in the ’60s (indeed, Nicholson was so exasperated by his lack of creative expression in these films that — by the time of Easy Rider — he was preparing to retire from acting to focus on writing and directing, additional vocations that he would indeed also perform for BBS). But Hopper and Fonda had more mythical aspirations, wishing to craft an allegorical counterculture western — not for nothing are their characters named Billy (the Kid) and Wyatt (Earp) — that would reflect a modern-day America that was rarely accurately portrayed by the studio system. The results indeed redefined Hollywood cinema of the era, culturally and financially (the film was, given its modest $350,000 budget, one of the most purely profitable productions of the decade). The film’s influence on the film industry has been so widely noted, and some of its most memorable qualities have been so widely imitated and parodied (“Born to Be Wild,” anyone?) that the actual merits of the film have tended to be neglected, or more commonly, dismissed. Easy Rider is rather widely critically berated these days (as it also was in many critical circles at the time of its release), and indeed, the film’s attempts at sociological profundity are often as clumsy and embarrassing as most dimly recalled pot-driven moments of shallow revelation, and they’re obviously long past their zeitgeist expiration date.

But there remains much to admire, principally Laszlo Kovacs’ deservedly renowned cinematography, and Hopper’s employment of it in service of framing the American landscape of “John Ford country” with a reinvigorated contemporary perspective. And the film’s innovative use of pre-existing songs as musical score is still potent — Steppenwolf may be the most famous example, but the cut from “Don’t Bogart Me” to Hendrix’s “If 6 Was 9” is a stunner. Easy Rider actually spawned more creatively vital if less financially successful imitations — from the fortunately rediscovered Two Lane Blacktop to the still underrated Electra Glide in Blue — but Hopper’s original endures and captivates on its own. Like many of the Criterion discs in the BBS set, the special edition of Easy Rider combines older, previously released supplementary features with new extras assembled exclusively for this version — in the case of this film, this allows for a multitude of differing accounts as to the film’s origins, with Hopper particularly eager to take sole credit for a screenplay co-written with Fonda and Terry Southern (as the film’s associate producer William Hayward observes, anecdotes surrounding the film’s production become “like a Rashomon story”). There are two documentary featurettes on the film, and two separate commentary tracks, one from an old laserdisc release featuring Fonda and production manager Paul Lewis accompanied by Hopper on a speaker phone (!), and another one recorded in 2009 with Hopper solo (be advised that this commentary is very sporadic and riddled with long silences, and would probably have been better served by editing into selected portion commentary, as the disc of King of Marvin Gardens has thankfully done).

Easy Rider was actually the second Rafelson and Schneider production, and was largely bankrolled by the success that Raybert Productions had enjoyed with “The Monkees” television series. When that program’s two-year run ended in 1968, Rafelson inaugurated Raybert’s film division with a feature film vehicle for the pre-fab pop quartet, Head (so titled because they wanted to advertise the production company’s subsequent effort Easy Rider as being “from the people who gave you Head”; alas, when the Monkees film received a dismal theatrical reception, one of the greatest potential poster taglines in history was scrapped). One’s personal tolerance for Head may depend considerably on each individual’s fondness for (or, in my case, tolerance of) The Monkees as performers; to me, this non-entity of a “rock band” makes other period poseurs like Strawberry Alarm Clock look positively Ash Ra Tempel-like in terms of psychedelic legitimacy. But then again, Rafelson’s film not only implicitly acknowledges the complete artifice of this pseudo-combo’s invention for the purposes of televised teenybopper titillation, but it addresses it Head-on in a satirical and subversive fashion, deconstructing the carefully formulated image of The Monkees in a way that was almost designed to alienate fans (think of it as the Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me of its day). Still, anyone expecting this madcap collection of tenuously connected sketches (written by Rafelson and Jack Nicholson) to be a pop fusion of Richard Lester and Performance should more realistically prepare themselves for a doped-up rerun of “Laugh-In” shot through with gratuitous Nguyen Van Lem cranial spurt inserts. Yet Rafelson’s direction is imaginative and the basic concept of reaffirming the spurious nature of The Monkees by setting the majority of the film in a rotating barrage of traditional cornball Hollywood studio backlot locations populated by everyone from Timothy Carey to Frank Zappa is inspired – and the songwriting of Harry Nilsson, the editing of Mike Pozen, and the choreography of BBS favorite Toni Basil combine to create one truly outstanding musical number, “Daddy’s Song.” The Head disc features a well-assembled commentary track with the four members of the band (each apparently recorded individually), a video interview with Rafelson, and a video piece on the history of BBS with critics David Thomson and Douglas Brinkley, as well as the usual collection of miscellany (trailers, screen tests, vintage TV interviews, etc.) that will be of obvious interest to Monkees fans.

Easy Rider was actually the second Rafelson and Schneider production, and was largely bankrolled by the success that Raybert Productions had enjoyed with “The Monkees” television series. When that program’s two-year run ended in 1968, Rafelson inaugurated Raybert’s film division with a feature film vehicle for the pre-fab pop quartet, Head (so titled because they wanted to advertise the production company’s subsequent effort Easy Rider as being “from the people who gave you Head”; alas, when the Monkees film received a dismal theatrical reception, one of the greatest potential poster taglines in history was scrapped). One’s personal tolerance for Head may depend considerably on each individual’s fondness for (or, in my case, tolerance of) The Monkees as performers; to me, this non-entity of a “rock band” makes other period poseurs like Strawberry Alarm Clock look positively Ash Ra Tempel-like in terms of psychedelic legitimacy. But then again, Rafelson’s film not only implicitly acknowledges the complete artifice of this pseudo-combo’s invention for the purposes of televised teenybopper titillation, but it addresses it Head-on in a satirical and subversive fashion, deconstructing the carefully formulated image of The Monkees in a way that was almost designed to alienate fans (think of it as the Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me of its day). Still, anyone expecting this madcap collection of tenuously connected sketches (written by Rafelson and Jack Nicholson) to be a pop fusion of Richard Lester and Performance should more realistically prepare themselves for a doped-up rerun of “Laugh-In” shot through with gratuitous Nguyen Van Lem cranial spurt inserts. Yet Rafelson’s direction is imaginative and the basic concept of reaffirming the spurious nature of The Monkees by setting the majority of the film in a rotating barrage of traditional cornball Hollywood studio backlot locations populated by everyone from Timothy Carey to Frank Zappa is inspired – and the songwriting of Harry Nilsson, the editing of Mike Pozen, and the choreography of BBS favorite Toni Basil combine to create one truly outstanding musical number, “Daddy’s Song.” The Head disc features a well-assembled commentary track with the four members of the band (each apparently recorded individually), a video interview with Rafelson, and a video piece on the history of BBS with critics David Thomson and Douglas Brinkley, as well as the usual collection of miscellany (trailers, screen tests, vintage TV interviews, etc.) that will be of obvious interest to Monkees fans.

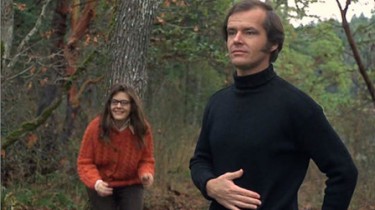

Rafelson’s follow-up to Head (and the first official BBS production) would reunite him with Nicholson, but this time as a lead actor rather than a co-writer, and the result, Five Easy Pieces (1970), was almost as culturally significant as Easy Rider — and, of course, it’s also a considerably better film. Whereas Nicholson’s supporting role in the previous year’s Easy Rider had already catapulted him to the stardom that had eluded him throughout the ’60s, his performance as restless, roaming Bobby Dupea cemented Nicholson’s status as iconic American actor for the decades that followed. His performance remains electrifying, and is propelled by the one quality that has seemed to characterize the actor’s most memorable roles over time — a charismatic talent for making seemingly unsympathetic characters not just compelling, but likeable. As a showcase for Nicholson’s presence, Rafelson’s film is a considerable achievement, and it’s a lamentably rare American film that is able to articulate male alienation and loneliness through an understated naturalism rather than the lazy catharsis of genre-driven violence. So…it’s perhaps ungenerous to gripe that the more pedestrian family drama of the film’s last half is a bit disappointing when contrasted with the looser, more haunting early section of the film, where not only Nicholson shines, but where one can envision entire alternate cinematic universes that could center around each of the supporting actors (including such BBS regulars as Karen Black, Toni Basil, and the wonderful Helena Kallianotes). Criterion’s disc features a solid commentary track with Rafelson and (recorded separately) his ex-wife Toby Rafelson, the film’s production designer; an excellent new documentary featurette on BBS containing interviews with most of the company’s major players; a quite lengthy 1976 audio interview with Rafelson; and a new video interview with Rafelson, specifically focusing on the film.

Rafelson’s follow-up to Head (and the first official BBS production) would reunite him with Nicholson, but this time as a lead actor rather than a co-writer, and the result, Five Easy Pieces (1970), was almost as culturally significant as Easy Rider — and, of course, it’s also a considerably better film. Whereas Nicholson’s supporting role in the previous year’s Easy Rider had already catapulted him to the stardom that had eluded him throughout the ’60s, his performance as restless, roaming Bobby Dupea cemented Nicholson’s status as iconic American actor for the decades that followed. His performance remains electrifying, and is propelled by the one quality that has seemed to characterize the actor’s most memorable roles over time — a charismatic talent for making seemingly unsympathetic characters not just compelling, but likeable. As a showcase for Nicholson’s presence, Rafelson’s film is a considerable achievement, and it’s a lamentably rare American film that is able to articulate male alienation and loneliness through an understated naturalism rather than the lazy catharsis of genre-driven violence. So…it’s perhaps ungenerous to gripe that the more pedestrian family drama of the film’s last half is a bit disappointing when contrasted with the looser, more haunting early section of the film, where not only Nicholson shines, but where one can envision entire alternate cinematic universes that could center around each of the supporting actors (including such BBS regulars as Karen Black, Toni Basil, and the wonderful Helena Kallianotes). Criterion’s disc features a solid commentary track with Rafelson and (recorded separately) his ex-wife Toby Rafelson, the film’s production designer; an excellent new documentary featurette on BBS containing interviews with most of the company’s major players; a quite lengthy 1976 audio interview with Rafelson; and a new video interview with Rafelson, specifically focusing on the film.

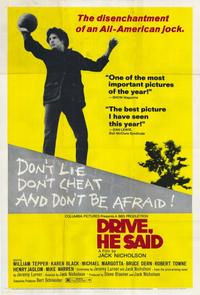

Shortly after Five Easy Pieces, Nicholson would make his directing debut with Drive, He Said (also 1970), which is paired with Henry Jaglom’s directing debut A Safe Place (1971) on the same Criterion disc, housing the two most forgotten obscurities in the BBS canon. I must admit that these were the only two BBS productions that I had not already seen (repeatedly) years before Criterion’s boxed set release, and while I would love to have been newly captivated by two rather neglected titles from the period, this was sadly not the case with the Nicholson effort. Adapted from a Jeremy Larner novel, Drive, He Said is a rather meandering and dated look at counterculture campus life, as a college basketball player balances the demands of his team and his coach (Bruce Dern, excellent here), an affair with a faculty wife (Karen Black), and a radical roommate whose impending Vietnam conscription sends him into madness. Unfortunately, the film’s clumsy improvisational approach and bold but rather purposeless sexual candor (the film was initially rated “X,” but was granted an “R” on appeal) fail to find any satisfying rhythm for exploring its characters, and Nicholson’s film emerges as an interesting misfire. Criterion’s presentation is also the most basic of all of the BBS titles, as the film is accompanied only by an 11-minute video piece on the production; Nicholson’s appearance here is brief, and one wishes that he had contributed more to a current appreciation of his inaugural effort as director.

Shortly after Five Easy Pieces, Nicholson would make his directing debut with Drive, He Said (also 1970), which is paired with Henry Jaglom’s directing debut A Safe Place (1971) on the same Criterion disc, housing the two most forgotten obscurities in the BBS canon. I must admit that these were the only two BBS productions that I had not already seen (repeatedly) years before Criterion’s boxed set release, and while I would love to have been newly captivated by two rather neglected titles from the period, this was sadly not the case with the Nicholson effort. Adapted from a Jeremy Larner novel, Drive, He Said is a rather meandering and dated look at counterculture campus life, as a college basketball player balances the demands of his team and his coach (Bruce Dern, excellent here), an affair with a faculty wife (Karen Black), and a radical roommate whose impending Vietnam conscription sends him into madness. Unfortunately, the film’s clumsy improvisational approach and bold but rather purposeless sexual candor (the film was initially rated “X,” but was granted an “R” on appeal) fail to find any satisfying rhythm for exploring its characters, and Nicholson’s film emerges as an interesting misfire. Criterion’s presentation is also the most basic of all of the BBS titles, as the film is accompanied only by an 11-minute video piece on the production; Nicholson’s appearance here is brief, and one wishes that he had contributed more to a current appreciation of his inaugural effort as director.

A Safe Place, on the other hand, is a different story. While it’s admittedly one of the lesser BBS productions (though significant in that it’s actually the only one to focus on a female protagonist), the film is nonetheless an intriguing debut for Jaglom, a director whose subsequent work could often be tiresomely self-indulgent and almost amateurish (earlier in the BBS history, it would be Jaglom who would greatly assist in editing Hopper’s original four-hour cut of Easy Rider down to a manageable running time). It would be tempting to dismiss Safe Place for some of those same flaws that would plague Jaglom’s other films — and many might indeed consider the film to be as tedious and frustrating as it is frequently charming and off-kilter — but the film’s portrait of a young Manhattan woman (a radiant Tuesday Weld) whose new romance is unsettled by childhood memories and present-day fantasies, is a uniquely haunting if wildly uneven endeavor. Jaglom makes effective use of a score composed of 1940s pop standards, and the improv nature of the performances actually allows for a few memorable and insightful sequences, particularly Gwen Welles’ direct-to-camera monologue about suicide attempts and sexual masochism, and the speech from Jack Nicholson about the appeal of murdering all of one’s former lovers. Jaglom is also a pretty engaging speaker throughout the disc’s special features, which include a commentary track, a 1971 video interview that Molly Haskell conducted with Jaglom and Peter Bogdanovich, and a collection of outtakes and screen tests (one of which, oddly, includes Paula Prentiss in Weld’s role). After all of this, I find myself tempted to revisit Jaglom’s later films with a new viewpoint.

A Safe Place, on the other hand, is a different story. While it’s admittedly one of the lesser BBS productions (though significant in that it’s actually the only one to focus on a female protagonist), the film is nonetheless an intriguing debut for Jaglom, a director whose subsequent work could often be tiresomely self-indulgent and almost amateurish (earlier in the BBS history, it would be Jaglom who would greatly assist in editing Hopper’s original four-hour cut of Easy Rider down to a manageable running time). It would be tempting to dismiss Safe Place for some of those same flaws that would plague Jaglom’s other films — and many might indeed consider the film to be as tedious and frustrating as it is frequently charming and off-kilter — but the film’s portrait of a young Manhattan woman (a radiant Tuesday Weld) whose new romance is unsettled by childhood memories and present-day fantasies, is a uniquely haunting if wildly uneven endeavor. Jaglom makes effective use of a score composed of 1940s pop standards, and the improv nature of the performances actually allows for a few memorable and insightful sequences, particularly Gwen Welles’ direct-to-camera monologue about suicide attempts and sexual masochism, and the speech from Jack Nicholson about the appeal of murdering all of one’s former lovers. Jaglom is also a pretty engaging speaker throughout the disc’s special features, which include a commentary track, a 1971 video interview that Molly Haskell conducted with Jaglom and Peter Bogdanovich, and a collection of outtakes and screen tests (one of which, oddly, includes Paula Prentiss in Weld’s role). After all of this, I find myself tempted to revisit Jaglom’s later films with a new viewpoint.

The two BBS productions that would follow in 1971 and ’72, and close their distribution relationship with Columbia, are also the company’s two best films, The Last Picture Show and The King of Marvin Gardens. The achievements of The Last Picture Show probably require minimal elaboration here — as J. Hoberman remarks in his excellent “One Big Real Place: BBS From Heads To Hearts” essay that appears in the boxed set’s accompanying 112-page booklet, “it’s possible that The Last Picture Show received better notices than any American movie between Gone with the Wind and The Godfather” — but I fear that I would be sadly inadequate with respect to that task regardless. Truthfully, I have viewed The Last Picture Show so frequently over the years — and the film has become such a personal cinematic fixation — that any chance of critical objectivity I may have once possessed is now long gone. Peter Bogdanovich’s adaptation of Larry McMurtry’s novel is something pretty close to perfect, and its accolades are certainly deserved. It’s also the most traditional or conventional of all BBS production (Schneider initially considered Bogdanovich to be too “square” to fit in with the group), and in that sense, the film is an interesting harbinger of the more commercially accessible direction that the 1970s “movie brat” directors would ultimately take towards the latter half of that decade. Just as Lucas and Spielberg created a new pop culture phenomenon by fusing the old-fashioned Hollywood genre pulp fodder and matinee fare with high-tech special effects, Bogdanovich essentially marries his love of the classical storytelling of Ford and Hawks with a newly permissive examination of small town sexuality.

The two BBS productions that would follow in 1971 and ’72, and close their distribution relationship with Columbia, are also the company’s two best films, The Last Picture Show and The King of Marvin Gardens. The achievements of The Last Picture Show probably require minimal elaboration here — as J. Hoberman remarks in his excellent “One Big Real Place: BBS From Heads To Hearts” essay that appears in the boxed set’s accompanying 112-page booklet, “it’s possible that The Last Picture Show received better notices than any American movie between Gone with the Wind and The Godfather” — but I fear that I would be sadly inadequate with respect to that task regardless. Truthfully, I have viewed The Last Picture Show so frequently over the years — and the film has become such a personal cinematic fixation — that any chance of critical objectivity I may have once possessed is now long gone. Peter Bogdanovich’s adaptation of Larry McMurtry’s novel is something pretty close to perfect, and its accolades are certainly deserved. It’s also the most traditional or conventional of all BBS production (Schneider initially considered Bogdanovich to be too “square” to fit in with the group), and in that sense, the film is an interesting harbinger of the more commercially accessible direction that the 1970s “movie brat” directors would ultimately take towards the latter half of that decade. Just as Lucas and Spielberg created a new pop culture phenomenon by fusing the old-fashioned Hollywood genre pulp fodder and matinee fare with high-tech special effects, Bogdanovich essentially marries his love of the classical storytelling of Ford and Hawks with a newly permissive examination of small town sexuality.

Criterion’s disc of The Last Picture Show is, rewardingly, the most extras-loaded release in their BBS set, in that it essentially compiles all of the supplementary features that have appeared on previous video incarnations of the title, as well as adding a few new ones. There are two commentary tracks, one from Criterion’s own 1991 laserdisc that features Bogdanovich and (recorded individually) actors Cybill Shepherd, Randy Quaid, Cloris Leachman, and Frank Marshall, and another new track with Bogdanovich solo; the recently deceased filmmaker George Hickenlooper’s 1990 documentary Picture This, shot during the production of The Last Picture Show’s ill-advised sequel Texasville; the hour-long The Last Picture Show: A Look Back featurette from the title’s previous 1999 DVD release; a new video interview with Bogdanovich; a brief interview clip with Francois Truffaut discussing the film; and various screen tests, location footage tests, and trailers. Be prepared: Bogdanovich began his career as a film journalist, interviewing a great number of legendary directors, and as a result, he has mastered the art of creating an anecdote for the purposes of interviews. This can be quite amusing — even with the ascots and bad Orson Welles impersonations — but it also means that if you are preparing to take in both commentary tracks, both documentary featurettes, and the new video interview, you better also be ready to hear several of the same stories — in very much the same way — five times (how he was introduced to the book by the late Sal Mineo, how McMurtry told him their filming location choice of Archer City “ought to be” perfect since that where the book was actually based, etc.). Unsurprisingly, the tale of how Bogdanovich dumped his wife, production designer Polly Platt, during shooting in favor of an affair with Shepherd, is not exactly covered as thoroughly.

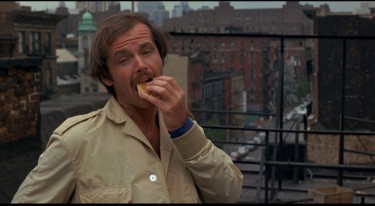

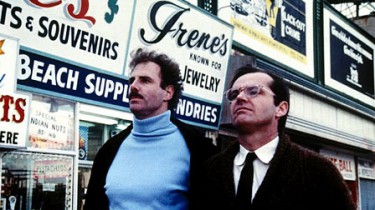

While The Last Picture Show displays the elegiac sense of melancholy and loss that seems to haunt so many of the BBS films, it seems positively jovial when compared to the final film that the company produced for Columbia, director Bob Rafelson’s The King of Marvin Gardens. Surely one of the bleakest and most despairing mainstream features to emerge from the “New Hollywood” of the 1970s, the film — like several of the previous BBS productions — is a dissection of the concepts of success and (particularly) failure as perceived in American society, and is another portrait of the disillusioned dreamers, fringe-dwelling outcasts, and quietly suffering loners who populate the edges of the American landscape. Nicholson reunites with Rafelson, but the intensity of their earlier creation of Bobby Dupea has been drastically reduced with the actor’s portrayal of David Staebler, a depressive late-night radio monologist in Philadelphia who’s dragged to a grim off-season (and pre-redevelopment) Atlantic City by his aspiring entrepreneur/hustler brother Jason (Bruce Dern, also outstanding here). The two siblings clash over Jason’s proposed real estate scheme, with Ellen Burstyn’s unhinged Sally and her stepdaughter trapped in the middle, and disastrous conflicts waiting in the wings. With its evocative setting of a grand old hotel largely empty in the winter months, and all of the isolation that this implies, The King of Marvin Gardens would make for an unlikely but appropriately eerie Nicholson double bill with The Shining (complete with supporting roles for Scatman Crothers in both films), and it’s my favorite of the three Rafelson-directed films included in the BBS collection — although, sadly, it was not a large success upon release (while it has certainly been reappraised in subsequent years, the film is still quite underrated), and that obviously didn’t help relations between BBS and Columbia during the final stage of their partnership. Rafelson recalls Hunter S. Thompson commenting on the film at its premiere, “That’s the best excuse for a cocaine habit I’ve ever seen,” and indeed, the film’s unrelentingly dour atmosphere may have proven too morose for some viewers (in the booklet essay, Hoberman notes that — while the release was actually profitable for Columbia — the New York Times recounts that the film received only a single positive review, in contrast to the 15 negative and five mixed notices it also garnered). The special features include a selected-scene commentary with Rafelson; a new video interview with the director; and also a 2002 video piece with Rafelson, Dern, and Burstyn.

While The Last Picture Show displays the elegiac sense of melancholy and loss that seems to haunt so many of the BBS films, it seems positively jovial when compared to the final film that the company produced for Columbia, director Bob Rafelson’s The King of Marvin Gardens. Surely one of the bleakest and most despairing mainstream features to emerge from the “New Hollywood” of the 1970s, the film — like several of the previous BBS productions — is a dissection of the concepts of success and (particularly) failure as perceived in American society, and is another portrait of the disillusioned dreamers, fringe-dwelling outcasts, and quietly suffering loners who populate the edges of the American landscape. Nicholson reunites with Rafelson, but the intensity of their earlier creation of Bobby Dupea has been drastically reduced with the actor’s portrayal of David Staebler, a depressive late-night radio monologist in Philadelphia who’s dragged to a grim off-season (and pre-redevelopment) Atlantic City by his aspiring entrepreneur/hustler brother Jason (Bruce Dern, also outstanding here). The two siblings clash over Jason’s proposed real estate scheme, with Ellen Burstyn’s unhinged Sally and her stepdaughter trapped in the middle, and disastrous conflicts waiting in the wings. With its evocative setting of a grand old hotel largely empty in the winter months, and all of the isolation that this implies, The King of Marvin Gardens would make for an unlikely but appropriately eerie Nicholson double bill with The Shining (complete with supporting roles for Scatman Crothers in both films), and it’s my favorite of the three Rafelson-directed films included in the BBS collection — although, sadly, it was not a large success upon release (while it has certainly been reappraised in subsequent years, the film is still quite underrated), and that obviously didn’t help relations between BBS and Columbia during the final stage of their partnership. Rafelson recalls Hunter S. Thompson commenting on the film at its premiere, “That’s the best excuse for a cocaine habit I’ve ever seen,” and indeed, the film’s unrelentingly dour atmosphere may have proven too morose for some viewers (in the booklet essay, Hoberman notes that — while the release was actually profitable for Columbia — the New York Times recounts that the film received only a single positive review, in contrast to the 15 negative and five mixed notices it also garnered). The special features include a selected-scene commentary with Rafelson; a new video interview with the director; and also a 2002 video piece with Rafelson, Dern, and Burstyn.

While the supplementary features on Criterion’s BBS set are a bit of a mixed bag in their collection of old and new interviews and commentary tracks, some assembled with Criterion’s typical precision and some clearly compiled outside of their care, there is very little to quibble about here. The presentations of the seven films are superb, and while the merits of the individual movies will obviously vary with each viewer’s personal opinion, this remains an essential chapter in American film history, and Criterion has presented it here with sufficient context for newcomers, as well as detailed insights and extra material that should please even those who have already acquired these films in various formats throughout the years. I don’t know whether it was an individual at Criterion Collection or Sony who coined the title “America Lost and Found” for this release, but it’s quite appropriate for many reasons. One can’t help but reflect that, as a production company, BBS reintroduced American cinema to a generation that had come to feel that the films being made no longer accurately represented their reality as people living in this country at that time. And if Roger Ebert’s dismissal of today’s younger generation of moviegoers is to be accepted at face value, then perhaps American cinema — whether mainstream or independent – has lost its ability to connect with the real concerns and feelings of its intended audience yet again. But if the enthusiasm some of these people have demonstrated towards films made during the revolutionary BBS era — before they were even born – are any indication, then perhaps it’s time for another cinematic insurgency. America lost and found, indeed.

[AMAZONPRODUCT=B003ZYU3SM]

[AMAZONPRODUCT=B003ZYU3SC]