Back to selection

Back to selection

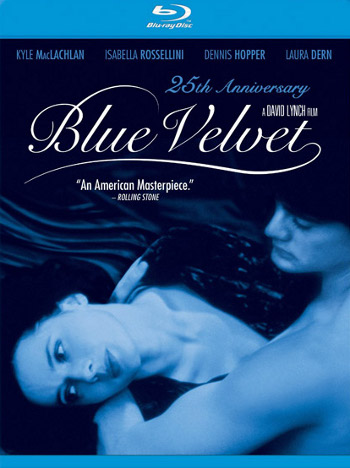

Blue Velvet 25th Anniversary Blu-Ray Edition

Blue Velvet remains a masterpiece of American cinema – one of the defining films of the 1980s, and arguably still director David Lynch’s best work (personally, I actually slightly prefer Lost Highway, but I’ve become gradually fatigued over the years with people looking at me like I’m insane when I divulge that) – and it still retains every bit of its power today. But to have seen it upon its original 1986 release was like experiencing a bomb going off inside the theater.  American films during the conservative Reagan decade were going through an awkward transitional period (and, outside of the interestingly thriving horror genre, one would be hard pressed to cite many great American movies from that era, although there were occasional exceptions such as William Friedkin’s riveting To Live and Die in L.A.). The Young Hollywood “golden age” of the 1970s was clearly experiencing its death throes, yet the alternative distribution patterns of the independent film explosion wouldn’t truly arrive until the end of the ’80s with sex, lies, and videotape and the ascension of Miramax. There were truly independent filmmakers experiencing varying degrees of success then – early Jim Jarmusch and Spike Lee, to name the obvious examples – but unless you were content to be a real outsider maverick (i.e. Jon Jost or Eagle Pennell), and you were making personal, medium-budgeted films, you were often thrown into the general release marketplace, and it was a case of sink or swim. Today, a film like Blue Velvet would do the typical film fest tour of duty, and then be gently placed into the Landmark-styled specialized theater circuit by a distributor like IFC, Magnolia, or Fox Searchlight. In 1986, producer Dino De Laurentiis had to release the film through his own newly established distribution company because no studio would touch the film, and Lynch’s disturbing psycho-sexual fever-dream melodrama went into a generally semi-wide release. At the age of sixteen, I saw the film on its opening Friday night at a small town suburban multiplex, and the largely middle-aged (and definitely middle-of-the-road) crowd was expecting just another critically acclaimed mainstream thriller.

American films during the conservative Reagan decade were going through an awkward transitional period (and, outside of the interestingly thriving horror genre, one would be hard pressed to cite many great American movies from that era, although there were occasional exceptions such as William Friedkin’s riveting To Live and Die in L.A.). The Young Hollywood “golden age” of the 1970s was clearly experiencing its death throes, yet the alternative distribution patterns of the independent film explosion wouldn’t truly arrive until the end of the ’80s with sex, lies, and videotape and the ascension of Miramax. There were truly independent filmmakers experiencing varying degrees of success then – early Jim Jarmusch and Spike Lee, to name the obvious examples – but unless you were content to be a real outsider maverick (i.e. Jon Jost or Eagle Pennell), and you were making personal, medium-budgeted films, you were often thrown into the general release marketplace, and it was a case of sink or swim. Today, a film like Blue Velvet would do the typical film fest tour of duty, and then be gently placed into the Landmark-styled specialized theater circuit by a distributor like IFC, Magnolia, or Fox Searchlight. In 1986, producer Dino De Laurentiis had to release the film through his own newly established distribution company because no studio would touch the film, and Lynch’s disturbing psycho-sexual fever-dream melodrama went into a generally semi-wide release. At the age of sixteen, I saw the film on its opening Friday night at a small town suburban multiplex, and the largely middle-aged (and definitely middle-of-the-road) crowd was expecting just another critically acclaimed mainstream thriller.

They were expecting something like Jagged Edge or Body Heat. They weren’t expecting a Kenneth Anger fusion of Last Tango in Paris and a nightmarish episode of Happy Days. Hearing audible gasps of horror during the film, and watching the stunned, confused expressions on audience members’ faces as they staggered out of the theater, was one of the happiest moviegoing memories of my teenage years, and I went back to see the film twice during its brief run. Although, having already been a huge admirer of Lynch’s feature debut Eraserhead, I actually found Blue Velvet to be disappointingly conventional and genre-based at the time…

They were expecting something like Jagged Edge or Body Heat. They weren’t expecting a Kenneth Anger fusion of Last Tango in Paris and a nightmarish episode of Happy Days. Hearing audible gasps of horror during the film, and watching the stunned, confused expressions on audience members’ faces as they staggered out of the theater, was one of the happiest moviegoing memories of my teenage years, and I went back to see the film twice during its brief run. Although, having already been a huge admirer of Lynch’s feature debut Eraserhead, I actually found Blue Velvet to be disappointingly conventional and genre-based at the time…

De Laurentiis was probably one of the last of the old school, genuinely creative producer-moguls, and he had made an informal handshake-based agreement with Lynch that he would finance Blue Velvet as a “reward” to the director for undertaking the thankless task of helming the bloated (albeit fascinating) production of Dune. Despite the disastrous reception afforded that adaptation (a project in which Lynch admitted he had little personal interest), De Laurentiis was a man of his word, and he agreed to continue with Blue Velvet, and give Lynch unofficial “final cut” (as explained in the “Mysteries of Love” documentary feature accompanying the film’s DVD and Blu-ray releases, De Laurentiis told Lynch that he couldn’t actually place a final cut clause in the contract because then every subsequent director would demand the same conditions, but this was another handshake deal that De Laurentiis did indeed honor). However, there was one condition: Lynch’s film could not run over two hours. If you examine much of Lynch’s other work – Wild at Heart, Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me, Lost Highway, Mulholland Dr., and certainly the often punishingly overlong Inland Empire – it’s easy to observe that the filmmaker typically prefers somewhat more expansive running times, and indeed, the original screenplay for Blue Velvet certainly reads like a blueprint for a film that would exceed a two hour timeframe. In its final theatrical release form, the film clocks in at just barely under 120 minutes, so it’s obvious Lynch was only respecting the stipulations of his contract by cutting down to the bone. In the years following the film’s release, Lynch – who has never expressed much enthusiasm for the idea of resurrecting deleted material for the video releases of his subsequent films – has lamented the loss of several excised sequences from Blue Velvet, but when attempts were made to find the removed footage, it couldn’t be located, and it was assumed that it had been lost following the collapse of De Laurentiis Entertainment Group in 1988-89 and the resulting scattering of the studio’s properties. The film’s previous 2002 special edition DVD release was only able to present glimpses of the deleted passages through a montage of surviving still photographs from the set, taken during the moments in question.

Well, flash forward to January of 2011, when Lynch revealed that – after years of absence – all of Blue Velvet’s excised footage had been suddenly located in storage in Seattle, and he was preparing to restore the material for a Blu-ray release. That Blu-ray special edition has just been issued, and it includes roughly fifty minutes of previously unseen scenes (this feature actually runs 51:42, but there is also an introductory title card by Lynch, as well as closing credits to identify the actors who exclusively appear in this footage); whether this report is accurate or not remains a mystery, but Lynch’s original rough cut reportedly ran almost four hours, so it is likely that the fifty minutes of material preserved here represents only that footage which Lynch is currently comfortable presenting. It is certainly fascinating to view these sequences that have remained hidden for the past quarter-century (!) – and there are indeed a few isolated moments that one wishes could have made the final theatrical release version – but anyone expecting major revelations among these scenes might be disappointed. Rather, they provide an intriguing insight into a direction that Blue Velvet thankfully didn’t adopt, and a glimpse into the methods that a filmmaker who is exploring challenging and tonally risky territory will utilize to cover himself in the editing process.

Lynch has admitted that the earliest draft of the Blue Velvet screenplay was unsuccessful because it dwelled too heavily on the ugliest and most violent components of the story, without enough warmth or tenderness to provide any balance (in other words, there’s weren’t enough “robins”). At the time of the film’s release, star Laura Dern remarked in interviews that she hoped audiences would still be able to see the hope and light in the film amidst all of the overpowering depravity and brutality. Much of the deleted material present on the new Blu-ray focuses on the romance between Jeffrey and Sandy, yet even more generally on the minutia of small town, apple pie Americana that is life in Lumberton. To give you an idea – among the deleted sequences, Dennis Hopper’s Frank character appears in only one scene and then two very brief shots (one of which is just a dialogue-free long shot), Isabella Rossellini’s Dorothy materializes for just one scene (that is actually just an extension of a scene that already exists in the theatrical release cut), and Dean Stockwell’s infamous Ben character doesn’t appear at all. The rest of the newly recovered material was definitely created by Lynch to provide a sweetness that he obviously feared would be distressingly absent from a film largely remembered for its sado-masochistic relationships, hauntingly dark and surreal imagery, and epic employment of creative profanity. Although it actually provides an indication of the type of homespun humor that Lynch would later employ in everything from Twin Peaks to his underrated The Straight Story, much of this deleted footage was – as is so often the case with these special edition supplementary materials – wisely deleted. A little of the comic relief from Jeffrey’s Aunt Barbara (the recently deceased character actress Frances Bay) goes a long way, and there’s quite a bit of that here.

While most of the deleted scenes are presented in chronological order as they would have originally appeared within the narrative, Lynch is no fool, and he kicks this featurette off with a bang and gives the audience what they’ve been waiting for all these years, even though it’s a moment that wouldn’t appear in the story until the 74-minute point of the existing version. Reportedly Lynch’s favorite sequence among the excised material, the “This Is It” bar scene runs about three minutes, and would have appeared between Frank’s legendary “Heineken?! Fuck that shit! Pabst Blue Ribbon!” exclamation at Jeffrey, and their subsequent entry into Ben’s lair (and, frankly, this scene’s potential interruption of an extremely effective and amusing cut is enough reason for its exclusion). The scene is actually nothing special – an old blues singer, some dancing nude women (one of whom has lit matches casually adorning her nipples), and Frank roughing up and threatening an associate he finds in the seedy tavern – but it’s gratifying to finally see it…and it also satisfies the nagging question of how Jeffrey, Dorothy, Frank, and his entourage could be entering a commercial bar that seems to be exclusively populated by Ben and a smattering of obese middle-aged women (this is now clearly a private room in the rear of the bar). Following that, there is perhaps the most extensive continued portion of deleted material, and that is the view of Jeffrey’s life at college before his return to Lumberton. Though it’s unnecessary backstory that was understandably eliminated, there is one bit that provides some enlightening (if obvious) foreshadowing of Jeffrey’s sexual turmoil and proclivity for voyeurism, as he spies on a date rape in the early stages of progress, and waits an uncomfortably long moment before intervening.

While most of the deleted scenes are presented in chronological order as they would have originally appeared within the narrative, Lynch is no fool, and he kicks this featurette off with a bang and gives the audience what they’ve been waiting for all these years, even though it’s a moment that wouldn’t appear in the story until the 74-minute point of the existing version. Reportedly Lynch’s favorite sequence among the excised material, the “This Is It” bar scene runs about three minutes, and would have appeared between Frank’s legendary “Heineken?! Fuck that shit! Pabst Blue Ribbon!” exclamation at Jeffrey, and their subsequent entry into Ben’s lair (and, frankly, this scene’s potential interruption of an extremely effective and amusing cut is enough reason for its exclusion). The scene is actually nothing special – an old blues singer, some dancing nude women (one of whom has lit matches casually adorning her nipples), and Frank roughing up and threatening an associate he finds in the seedy tavern – but it’s gratifying to finally see it…and it also satisfies the nagging question of how Jeffrey, Dorothy, Frank, and his entourage could be entering a commercial bar that seems to be exclusively populated by Ben and a smattering of obese middle-aged women (this is now clearly a private room in the rear of the bar). Following that, there is perhaps the most extensive continued portion of deleted material, and that is the view of Jeffrey’s life at college before his return to Lumberton. Though it’s unnecessary backstory that was understandably eliminated, there is one bit that provides some enlightening (if obvious) foreshadowing of Jeffrey’s sexual turmoil and proclivity for voyeurism, as he spies on a date rape in the early stages of progress, and waits an uncomfortably long moment before intervening.

But after these interesting sequences, there is a lot of Lynch’s “Aw, shucks, gee whiz”-styled faux-naïve Lumberton life, with a particular emphasis on Jeffrey’s strained home life with his mother and Aunt Barbara, and also a more detailed look at Jeffrey’s intrusion into the high school relationship between Sandy and Mike. Some of this footage is truly unnecessary exposition (Jeffrey arriving back home at the airport) and some of it also consists of simple extensions of scenes that appear in the theatrical cut in abbreviated form, but there are still some worthwhile images (more spellbinding tracking shots of the wind blowing through tree leaves at night). Amidst all of this, it’s worth emphasizing one low point, and one highlight. In the former category, there’s additional footage at The Slow Club where Dorothy sings (though nothing with Rossellini), and the passages – a dog inexplicably eating on stage as if delivering a performance, and an intentionally unfunny stand-up comic – prefigure Lynch’s worst tendencies towards self-parody, and also illustrate his occasional visual clumsiness (as with many painters-turned-filmmakers, he sometimes confuses the beauty of an assured full-frontal tableaux composition with a static inability to move the camera when necessary). But in the area of highpoints, the sole new sequence with Rossellini – again, an extension of a scene that appears late in the cut of the theatrical version – is extraordinary. Fleeing to her apartment building’s rooftop in a flirtation with suicide, hovering over the ledge with her arms extended like a bird in desperate flight as Jeffrey nervously approaches from behind and attempts to coax her down, the scene is among the most heartbreaking in the film (in which it does not appear), and it is both a powerful representation of Dorothy’s self-destructive masochism, and a poignant and passionate example of Jeffrey’s genuine affection for her, as they embrace upon her retreat. If there was any of these moments that deserved inclusion in the final cut of the film, this would definitely be it – and I would have happily sacrificed a minute or two of Jeffrey fooling around with a bug-spraying unit to have made room.

“A Few Outtakes” is the only other significant feature new to this Blu-ray, and it’s merely 93 seconds of bloopers (although even using the words Blue Velvet and “bloopers” together is undeniably bizarre), and the rest of the special features have been ported over from the previous DVD: a selection of trailers and TV spots, the original Siskel & Ebert review of the release in 1986, and the excellent 71-minute “Mysteries of Love” retrospective documentary on the film (there are also a few brief “Vignettes,” which appear to be deleted interview material from this feature). As for the feature itself, Blue Velvet has never looked or sounded better, and while it would be easy to say this new Blu-ray is comparable to the DVD from several years ago, this release is actually a notable improvement over that (already quite good) release – how much of that is simply attributable to the high definition upgrade, or whether there has been additional tweaking of the transfer, is unknown.

“A Few Outtakes” is the only other significant feature new to this Blu-ray, and it’s merely 93 seconds of bloopers (although even using the words Blue Velvet and “bloopers” together is undeniably bizarre), and the rest of the special features have been ported over from the previous DVD: a selection of trailers and TV spots, the original Siskel & Ebert review of the release in 1986, and the excellent 71-minute “Mysteries of Love” retrospective documentary on the film (there are also a few brief “Vignettes,” which appear to be deleted interview material from this feature). As for the feature itself, Blue Velvet has never looked or sounded better, and while it would be easy to say this new Blu-ray is comparable to the DVD from several years ago, this release is actually a notable improvement over that (already quite good) release – how much of that is simply attributable to the high definition upgrade, or whether there has been additional tweaking of the transfer, is unknown.

I haven’t written much about the qualities of the actual film because, firstly, I assume most anyone reading this has already seen Lynch’s work, and secondly, I am also faced with the same dilemma with which I was confronted when attempting to write about The Last Picture Show for this very site last year. Some films have been such a part of an individual viewer’s sensibilities for so long, and with such depth, that an analysis would be like trying to be objective about your own DNA. I’m not up to it – but you already know that this is essential viewing, and the Blu-ray is pretty mandatory too.

Read more about Blue Velvet at Nicholas Rombes’ The Blue Velvet Project.

[AMAZONPRODUCT=B005HT400A]