Back to selection

Back to selection

Gerard Ravel and the Super 8 Festival that Launched J.J. Abrams

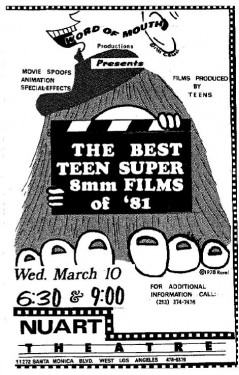

In Super 8, writer/director J.J. Abrams (pictured) tells the story of a group of adolescent filmmakers in a small Ohio town whose big dream is to get their film into the fictional Cleveland International Super 8 Film Festival. The film never shows us if their movie makes it — the kids are sidetracked by an alien invasion, after all — but in real life Abrams was part of a real life band of teen filmmakers showcased at a festival titled “The Best Teen Super 8mm Films of ’81.” Held at L.A.’s Nuart Theater in March 1982, it helped launch the career of not only Abrams (director of the Star Trek reboot, and creator of TV’s Alias, Lost, etc.), but a whole community of film and TV talent. Matt Reeves, who went on to co-create Felicity with Abrams and direct films such as Cloverfield, was there with his 28-minute Hitchockian thriller Stiletto. Larry Fong, the cinematographer for Lost and Super 8, screened his 15-minute spoof Toast Encounters of the Burnt Kind. The event also boasted films from less-heralded talents like screenwriter Mark Sanderson (I’ll Remember April, Silent Venom), who screened his film The Last Silent Swordsman, and the broader circle of filmmaking friends working with the participants included actor/writer Greg Grunberg (co-star of the TV series Heroes) and producers Bryan Burk (Star Trek, Super 8, Mission: Impossible: Ghost Protocol) and Lawrence Trilling (NBC’s Parenthood).

In Super 8, writer/director J.J. Abrams (pictured) tells the story of a group of adolescent filmmakers in a small Ohio town whose big dream is to get their film into the fictional Cleveland International Super 8 Film Festival. The film never shows us if their movie makes it — the kids are sidetracked by an alien invasion, after all — but in real life Abrams was part of a real life band of teen filmmakers showcased at a festival titled “The Best Teen Super 8mm Films of ’81.” Held at L.A.’s Nuart Theater in March 1982, it helped launch the career of not only Abrams (director of the Star Trek reboot, and creator of TV’s Alias, Lost, etc.), but a whole community of film and TV talent. Matt Reeves, who went on to co-create Felicity with Abrams and direct films such as Cloverfield, was there with his 28-minute Hitchockian thriller Stiletto. Larry Fong, the cinematographer for Lost and Super 8, screened his 15-minute spoof Toast Encounters of the Burnt Kind. The event also boasted films from less-heralded talents like screenwriter Mark Sanderson (I’ll Remember April, Silent Venom), who screened his film The Last Silent Swordsman, and the broader circle of filmmaking friends working with the participants included actor/writer Greg Grunberg (co-star of the TV series Heroes) and producers Bryan Burk (Star Trek, Super 8, Mission: Impossible: Ghost Protocol) and Lawrence Trilling (NBC’s Parenthood).

Perhaps most significantly, the festival introduced Abrams to future Super 8 producer Steven Spielberg, who after reading an article about it in the Los Angeles Times (titled The Beardless Wonders of Film Making) hired Abrams and Reeves to clean his old teenage 8mm films and repair the splices for $300.

The festival was the brainchild of Gerard Ravel, the 35-year-old host of the local public access show Word of Mouth who had previously toured the country screening surfing films at repertory cinemas and would later go on to found NSI Video, a leading distributor of skateboarding and surf videos.

On the eve of Super 8‘s DVD/blu-ray release, we tracked down Ravel (who now works as a real estate agent in Hermosa Beach, CA) to talk about what it was like to work with Abrams and company in the days before cell phone video cameras and the internet turned DIY filmmaking and distribution into an anyone-can-do-it proposition.

Filmmaker: Were you always an entrepreneur?

Ravel: I have an acting background. I was born in Burbank, but we lived in Hollywood. My dad was a character actor back in the I Love Lucy days. I was an actor when I was two-years old in An American in Paris with Gene Kelly. When I was 8, I did puppet shows in my parents’ living room and charged kids five cents apiece to come in and watch.

Filmmaker: What inspired you to start your public access TV show Word of Mouth?

Ravel: Public access was our YouTube. That was the only way you could produce a show and get it aired. When we started the show, it was a 30-minute interview showcase format, which was a great way for me to invite on talented people. The first person I had on was Fred Crippen [Roger Ramjet, Skyhawks, etc.], an award-winning animator who owned Pantomime Pictures. After that, we started adding artists, musicians and filmmakers to come on the show. The whole idea was to promote everybody, because there was no way to do it in those days. Then I discovered that this was a great opportunity for me to find talent I could use later — musicians, actors and filmmakers — and eventually produce our own movies.

Filmmaker: How did you start bringing on amateur Super 8 filmmakers?

Filmmaker: How did you start bringing on amateur Super 8 filmmakers?

Ravel: That was a surprise. At the end of our show, I’d say, “If you know anyone or you’d like to come on, here’s our phone number. Give us a call.” One day, I get a message on my phone machine. It said, “My name is J.J. I’m 15-years old. I’ve been making films for seven years, and I would like to be on your show.” I thought it was a prank… because most of my audience was older. So I called the number and I went over to his home [in L.A.’s Pacific Palisades neighborhood] and met him and his parents. They were really nice people and J.J. was one of the most polite, courteous kids I ever met. He loved working with makeup and special effects. He put the films on his Super 8 projector, and I knew this kid was going to make it. His enthusiasm was over the top, and as soon as I saw him, I said, “You know what? He’s going to be a great interview. He’s going to inspire other people to call my show.” We ended up doing two shoes [with Abrams]. Then the next week I get another call, and it’s Matt Reeves. He says, “I’m 15-years old. I saw J.J.’s films on your show. I have a 30-minute film and I’d like to be on your show.” That’s when I knew I’d struck a chord, because now all of these kids who were wanting to be filmmakers were watching my show.

Filmmaker: Showing their films also helped with your bottom line.

Ravel: It was pretty much all about costs. I had to pay for everything and public access didn’t allow commercials. When I would interview a filmmaker and then show their films, I could actually do three interviews in one day, two interviews the next, transfer their films to video and edit a 3/4-inch master for under $150 per show. There was no way I could do that with anything else.

Filmmaker: When did you decide to do the festival?

Ravel: After Matt and J.J. were on, then we said, ‘What if we did a show at the Nuart Theater [an art house theater in West Los Angeles], and they both were enthusiastic. Between Matt and J.J., I had 90 minutes of short films. So we decided to book a matinee at the theater with only those two guys called “The All-New Teen Super 8 Film Festival.” We charged $3.50 per ticket… and it was successful. We all looked at each other and said, “This is what we want to do.”

Filmmaker: When was this?

Ravel: It was in October of 1981. I said, “But where are we going to get new films. We can’t play the same ones.” J.J. looked at me and said, “I’m working on a film right now. It’s called High Voltage. I’ll have that done on Super 8, finished and in the can in three weeks.” I said, “What?!” You have to understand that he was only 15 at the time. He had some car chases, so his grandma let me drive the car. Dom DeLuise’s oldest son [Peter, who later starred opposite Johnny Depp on the TV series 21 Jump Street] was the star of the film. He was one of J.J.’s friends; they went to school together. I did all the lighting. I was the transportation. I used to work for the studios at [IATSE] Local 33 [stagehands union] for about seven years, so I knew how to do all that. J.J. would write and direct and I would basically produce, and we kept running around getting all these different locations and finished it in three weeks. We had a small article in the L.A. Times about the matinee show, so other people started calling us about their films, including Larry [Fong].

Filmmaker: You said you had agencies scouting the festival.

Ravel: Creative Artists Agency was there. People were coming up to me and saying, “If you know of anyone that should come in our direction, our door is always open to you.” Everybody was looking for new talent. Steven Spielberg secretary called us and said that Steven wanted to see J.J.’s movie High Voltage. That’s where J.J. was introduced to Steven.

Filmmaker: Your plan to strike a 35mm print of the films and take it to repertory cinemas around the country never panned out. Did the whole thing just peter out?

Ravel: Absolutely not. We ended up doing “The Best Teen Films of ’82,” and we had Scott Alexander, who got an Academy Award for [co-writing the script for] The People vs. Larry Flynt. He approached us with a couple of short films he had. One was called Myron and another was called “Cinemontage.” I could tell he was extremely talented, And that year we not only got into the L.A. Times, but [film critic] Gary Franklin put us on the [KCBS-TV] news for about five minutes, showing different clips and saying that our show was an 8 on a scale of 1-to-10 and there were better films coming out of our show at the Nuart than there were coming out of Hollywood. It’s amazing. At that show, Norman Lear and Jean Stapleton [producer and co-star, respectively, of All in the Family] were there. Louis L’Amour, the famous Western writer, was there, because his son was directing one of the pieces. It was unbelievable. We did it again ’83 and ’84, and then I started running out of money. What I should’ve done was probably got some investors, to be honest with you.

Filmmaker: So you ended up getting out of Super 8 and moving into skate films?

Ravel: I had to make some money. I knew all the surfers. I had helped them promote their surf movies in theaters and stuff. That’s why I was so successful with the Nuart idea. I was the one who came up with the idea of putting surf movies on video. Because at the time [home] video was just coming into its own. And all you could get were feature films at the time. I started at Video Archives, [the video store in Manhattan Beach, CA] where Quentin Tarantino worked. I put one tape in the store for two weeks, and it turned out that it rented more than the feature films. So I became a distributor, and then everybody started giving me their surf movies. And then I started with skate and, in three years, I had 2500 video stores [around the world] buying from me. I was working out of my garage and I was netting $3000-a-day, 24-7. Of course, I was working seven days a week. So I did that for quite awhile.

Filmmaker: Did you stay in touch with Abrams all this time, or did you just watch from the sidelines as he scored script, TV series and movie deals?

Ravel: I noticed when he and Matt were doing Felicity. Did I keep in contact enough? No. That was my one big regret. But I’ve been in contact with J.J. at least once a month now.

Filmmaker: You reconnected when he appeared on The Jimmy Kimmel Show and they showed the L.A. Times article with you, Abrams, Reeves and Sanderson posing in front of the Nuart.

Filmmaker: You reconnected when he appeared on The Jimmy Kimmel Show and they showed the L.A. Times article with you, Abrams, Reeves and Sanderson posing in front of the Nuart.

Ravel: I heard he was doing the movie Super 8; that’s our tie. So I found out that he was going to be on The Jimmy Kimmel Show on June 9, 2011. So I go to pull out the shows that we did, and the air date was June 9, 1981 — exactly 30 years difference. I said, “This is a sign. I need to call the Kimmel producers.” I call them, they took the newspaper article, they took the clips from the show… [but] they didn’t tell J.J. I was in the audience. At the end of the show, the producer comes over and says, “J.J. heard you’re here.” I go into the green room, and he looks just the same as he did when I knew him. Same attitude. Sweet, nice person. I go to shake his hand and he gives me a big bear hug and says, “Where have you been?” I go, wow, here’s a guy making $17 million a year and he actually remembers. That was amazing to me. I went down to his Bad Robot production company and we’ve been talking pretty much ever since.

Super 8 photos courtesy of Paramount Home Entertainment.