Back to selection

Back to selection

Director Marten Persiel Discusses This Ain’t California

This Ain't California

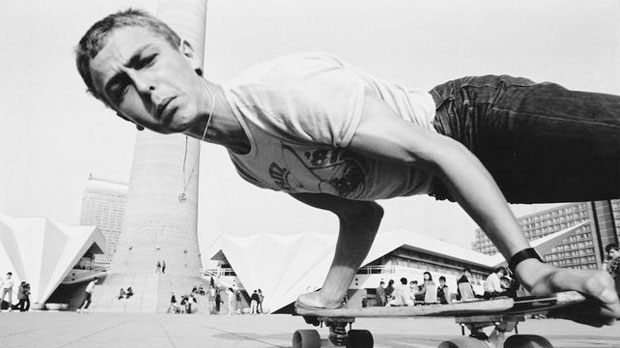

This Ain't California A while back I wrote about Marten Persiel’s This Ain’t California, the Berlinale-winning “punk fairytale” about skateboarding in East Germany that caused a bit of a stir overseas for its liberal use of staged reenactments. Regardless of the controversy, Persiel’s film is like nothing I’ve seen in recent years, the closest comparison probably being Grant Gee’s 2007 Joy Division (written by Jon Savage), which employs a collage of images to conjure up the Manchester atmosphere during that music scene’s heyday. In fact, Manchester and East Berlin shared a similar aesthetic in the ’70s and ’80s, composed of drab grey buildings and cold concrete, out of which an artistic community counter-intuitively blossomed like flowers springing from pavement cracks. Communism might not have ruled Thatcher’s England, but the sense of hopelessness that originally birthed the Sex Pistols’ No Future is the same that propelled the GDR’s skater culture. And as someone who grew up punk in small town Colorado during the Reagan days, This Ain’t California is my story as well. Ich bin ein Californian.

Filmmaker spoke with the German director prior to the film’s U.S. theatrical premiere at the Maysles Cinema on April 12th.

Filmmaker: So how did the idea of making a doc about the first East German skateboarders come about? Did you know these “Ossis” from back in the day? Did you stumble upon a treasure trove of found footage?

Persiel: It started during a skate session in East Berlin. We were looking at some GDR building with big sweeping concrete slopes on either side, that were once meant to show the sovereignty of socialist ideals. Almost as a joke I said to my buddy, “Let’s make a comedy short about a guy that invents skateboarding in the east and doesn’t know it already exists!” It was meant to be a fun short movie. I found Ronald Vietz, the producer, not much later, and together we went on a research mission. As it turns out, the story of skateboarding in socialist Germany is by no means just a joke – it happened – and it’s a story that carries much more than cheap laughs at the expense of “Ossis” who were ignorant of the developments in the west. After about a year of research, after finding more and more photos and film material of the maybe 200 skaters that existed, we realized that we could make a proper cinema film out of it. It was scary at first – I had never done 90 minutes before – so writing and directing it was a huge challenge, but with the incredible support and stamina of Ronald and the rest of the team, we just somehow improvised our way through those three years of mayhem. The love for skateboarding was a guide – as was the fact, that in one way or another, we all describe something of our childhood in the film. It was a very personal project.

Filmmaker: This Ain’t California certainly speaks to a particular demographic. I spent my teenage years at hardcore punk shows and new wave nightclubs in the 80s, so a lot of your footage feels like my very own home movies. But what’s been the response from younger generations, both in Germany and beyond? Is the doc a curious artifact, or a film they can actually relate to as well?

Persiel: I tried not to focus on the specifics of politics and history, but rather look for a sort of universal feeling of what it feels like to be young, to go out and skate, to find your way through a world owned by grown-ups. We all have gone through that phase, and generally it’s a time in life when some of the most emotional memories are created. In screenings with audiences both in Europe and abroad, I get a lot of people of all ages commenting on that very aspect. They say the film feels like being young, looking into the world with those eyes of possibility, with a lust for laughs and drama, and sex and adventure. On the other hand, I think people like you and me, our generation, the generation I speak about in the film, will always have special access to music like Anne Clark, Die Ärtze, Alphaville, Eight Dayz, and yes, those moments are for us, but in general, I tried to make a film that will work as well for my mother as it might for a teenager in Korea.

Filmmaker: The beauty of skateboarding, which represented artistic freedom and camaraderie to those on both sides of the Wall, is its neutrality. Especially for the young East Berliners it was one of the few activities they could engage in that transcended politics and country. It’s the same with music, which along with inventive animation, you use to terrific effect in This Ain’t California. Could you talk a bit about the importance of the relationship between the film’s images and its soundtrack?

Persiel: I am not sure what you are asking exactly, but just as a leap of faith: Yes, I think This Ain’t California is a film that tried to put some skateboarding attitude into how it was made, in the sense that we didn’t follow the trodden roads of documentary filmmaking. The film has hand-drawn animation, a feature film-like soundtrack, and some moments of montage that are more stoned stream-of-consciousness than tight storytelling. I wanted to tell a true story in a way that works in the tummy, not in the head, and I didn’t really care about what is “allowed” in a documentary. During those 90 minutes you can’t ever really know what is going to happen next; it’s spontaneous and it’s not political education. It’s like skateboarding in a way. It’s a ride.

Filmmaker: The doc provides a bit of historical context through the chop-chop edited archival footage at the opening, and a talking head who was a former Stasi agent at the time, but mostly you focus firmly on this group of friends rebelling against rules and authority like any other teens the world round. (And who subsequently lose touch with one another after the Wall falls, which really serves as a metaphor for growing up and being left with nothing to fight against anymore.) Was this choice made in order to universalize the story, or did you have difficulty finding political subjects to interview?

Persiel: You kind of said it there. Like I said before, I wanted to keep it general and sort of independent of too many political and historical facts that would make it into a more precise but also a drier experience.

Filmmaker: I found it quite interesting that those who knew the fearless, anti-authority “Panik” – who is described as a “Jesus figure” for the skateboarding scene at one point – would be surprised upon learning that he joined the military in the late ’90s. To me it makes perfect sense, for the armed forces are made up of bands of brothers who fight together – a recreation of rebellious teen spirit in a way. Did you ever feel compelled to contact those outside the skaters’ circle who knew Denis (as opposed to “Panik”) in order to dig past the myth?

Persiel: Our research was very extensive, and naturally we looked into the backstory of Panik’s life between 1989 and 2011, including his motivations for joining the army. I agree with you, the army can have a valuable function for a certain type of person. Panik was part of a generation of young males who were thrown into a new world and often left to find some sort of fixed points to rely on. He was basically lost, and he couldn’t really see a future for himself, maybe because he wrongly thought he had nothing really to offer anyone. So joining the army saved him for a while, until it killed him. I absolutely disagree with you that there is any heroism in that – or any rebellious spirit. Panik the loner, the lost soul, seeking refuge in a “band of brothers” as you call it, makes perfect sense. Panik the artist, the authority-hating rebel, killing other young men for political motivations doesn’t. Panik the skater kid from socialist Germany, dying for the oil-lust and religious righteousness of the west, is as absurd to me as it is to the skaters that I interviewed. There’s a saying that the army will make “boys into men.” That’s great for anyone who feels they need a boost in that department. Lance Mountain, one of the founding fathers of modern skateboarding, put it like this, “Skateboarding is a way to stay as immature as possible for as long as possible.” I think it is justified to ask with bewilderment, as Hexe does in the film, “How did the skater turn into a soldier?”