Back to selection

Back to selection

Five Questions with Let The Fire Burn Director Jason Osder

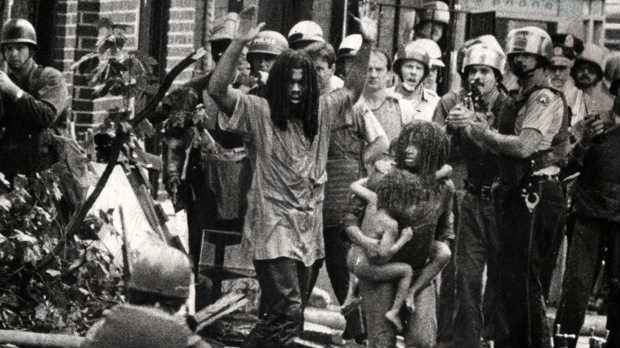

Founded in 1972, the Philadelphia-founded black liberation group MOVE Organization (the capitals break down into an acronym) preached a return to nature, annoying their neighbors by having bullhorns broadcast their beliefs all night and letting garbage fester in their yard. On May 13, 1985, Wilson Goode — the city’s first black mayor — approved dropping a bomb on their house as part of an eviction effort. 11 MOVE members died, including 5 children, and destroyed 61 houses. Jason Osder’s documentary feature debut Let The Fire Burn resurrects the incident almost exclusively through archival footage of TV broadcasts, home movies and other contemporary footage. Osder’s academic career includes a degree in praxis philosophy from New College of Florida, and he’s been a professor at George Washington University, teaching classes on digital media and documentary production. The film premieres at Tribeca today, and Osder answered questions in advance through email.

Filmmaker: A degree in praxis philosophy indicates political commitment dating back a fair way. If I understand how the New College of Florida works properly, that means creating a course of study for yourself. How has your academic background has influenced this political project?

Osder: While I follow your train of thought, the implications are a lot less specific than you imply. New College has a intense commitment to the principles of liberal arts education with a twist of pure individualism. I think it has been influential in everything I have done with my career. I saw praxis less in its political (Marxist) sense and more in a philosophical sense: that theory and practice are not actually dichotomous, but more like a dog chasing its tail. I reject the Cartesian implication that thought and knowledge are inextricably related. I believe there is knowledge in the hand, the eye, and the artifact. Seems a relevant thought to all I have done, but documentary and this project are the epitome for me.

Filmmaker: How long have you been aware of MOVE’s story and at what point did you decide it was important for you to bring it back into documentary discourse?

Osder: I remember it from when I was a kid. When I moved away from Philadelphia, I was shocked and saddened that an event that had been meaningful (and shocking and frightening) to me was unknown by many Americans my own age. When I went to film school for documentary, I learned a more specific rubric for vetting documentary ideas and I started to place this story against this rubric and thinking about the film.

Filmmaker: Was there a moment you felt that without this film, this story wouldn’t be re-examined in a documentary?

Osder: I don’t think I ever thought about it that way, but at a work-in-progress screening with a high school group, a particularly precocious young woman asked me, “Do you think this is your calling?” That one gave me pause.

In truth, there was a long while that I was failing to make the film and it would have made sense to give it up. I found that I lacked the constitution to give it up. I just kept working on it, but for a while I didn’t think about finishing, it was just an activity. I used to joke that I would either finish the film or die trying. I was actually OK with that, at a point.

Filmmaker: “Post-racial America” is a oft-invoked chimera that doesn’t exist. Your movie focuses on the recent past, implicitly nudging us to consider a moment that isn’t part of our officially healed civil rights history and how it relates to our present ability to discuss race, or lack thereof. Do you have a projected audience that will change their thinking on race in America, or are you more invested in educating a willing audience that’s simply ill-educated on this front?

Osder: I have a theory about this that is generational. I believe that starting with my generation (Generation X, the Hip Hop generation, whatever) American culture is ready for stories that deal with race but do not totally collapse into race.

The MOVE story is complicated and I wanted to preserve those complexities. It is a story about race relations in America, but it is also about police power, agency, class, bureaucratic power, and etc.

I believe that race in America is inherently complex and has too often been flattened and simplified in film (docs and fiction). I think we are ready to tell and hear stories that have race as an element but where it does not eclipse other (overlapping, interweaving) aspects of power and prejudice. If these stories (and this film) can lead to generative conversations in this area, I am all for it (but it may be difficult).

Filmmaker: Is there any information you’d be willing to share on Art And Annie, which is listed as your next project?

Osder: That project was discontinued. I had planned a portrait piece on an elderly father and daughter dealing with disability. I soon realized that the way to cover these lovely people was longitudinally, and I did not have the bandwidth to stick with it for the long haul.

I am now researching a new film about another incident from 1985: the assassination of an Arab American activist and accusations that a domestic Zionist organization was responsible. I am working with a colleague at GW and it is still too early to know if there is a film here.