Back to selection

Back to selection

Drew DeNicola and Olivia Mori on Big Star: Nothing Can Hurt Me

It’s a golden era for “forgotten musical acts of the ’60s and ’70s” docs. While Malik Bendjelloul’s Searching for Sugar Man took home the BAFTA and an Academy Award for Best Documentary earlier this year, following a wave of acclaim after its Sundance premiere, films like Jeff Howlett and Mark Christopher Covino’s A Band Called Death, Jay Bulger’s Beware of Mr. Baker and Morgan Neville’s Twenty Feet from Stardom have ridden the festival circuit praise to their own well-received releases in recent months.

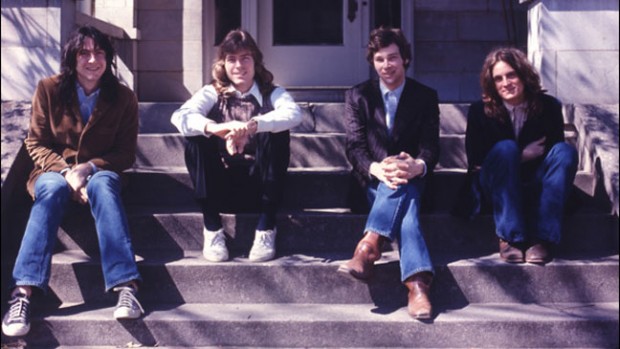

Next in line is Drew DeNicola and Olivia Mori’s Big Star: Nothing Can Hurt Me, an assured, rather handsome look at the seminal yet nearly forgotten 70’s power pop act whose three critically acclaimed albums in the early to mid ’70s never quite found the audiences they deserved. The band, which came of age in Memphis in the heyday of stalwart Bluff City labels Stax and Sun Records, was racked by various kinds of turmoil be it poor distribution, record industry tomfoolery and finally personal tragedy. Still the contents of the three ’70s albums (a reconstituted version of the band produced a fourth in 2005), 1972’s ironically titled #1 Record, 1974’s Radio City and 1978’s Third/Sister Lovers, stand up with the classics of the era. Routinely cited by bands such as R.E.M. and Oasis as a major influence, they stand to be introduced to a brand new generation of listeners by DiNicola and Mori’s film.

This is a first feature for co-directors DeNicola and Mori, who come from varied backgrounds as filmmakers. While Mori cut her teeth as a deputy costume designer on indies such as Asia Argento’s The Heart is Deceitful Above All Things, John Cameron Mitchell’s Shortbus and Ang Lee’s Taking Woodstock, DiNicola has plied his trade as an editor for VICE Media and MTV while at work on this film and another feature doc still in post-production, Natural Soul Brother. Big Star: Nothing Can Hurt Me bowed at SXSW 2012 before making the festival rounds with stops at Sarasota, Seattle and CIMMFest. Magnolia Pictures opened the film at IFC Center in Manhattan this week.

Filmmaker: When did you first become familiar with Big Star’s music and what was the catalyst for wanting to tell their story?

DeNicola: I’m a child of the ’90s, and they were definitely being talked about at that time. Thanks to a lot of rock publications like Rolling Stone, they were always listed as having made some of the best records of all time. I started to realize that that designation was slipping by the time we made the film. I didn’t hear people talking about Big Star as much anymore. Once we started working on the film, it became apparent to me that no one under thirty knew anything about Big Star.

Mori: For our generation, unless they were super into music, wouldn’t have heard of them.

DeNicola: It did get to the point where bands like Oasis, and Creation Records, and when Alex [Chilton, Big Star’s frontman] died, Alan McGee wrote an obituary for Alex that suggested Big Star was the whole basis of their record label and what kind of music they wanted to make. So they really did achieve great heights of influential acknowledgement, but that was 15 years ago.

Filmmaker: Were you previously familiar with the Memphis music scene that Big Star came of age within? The interesection between the rock and R&B worlds in that town are some of the most interesting aspects of the film.

Mori: There were several books that really laid out for you the whole scene. Once we got down to Memphis, we originally planned a three-week shoot, but we realized there was so much more story than we had originally imagined. We spent a lot of time getting to know people. so many phone calls and pre-interviews, just getting the lay of the land.

DeNicola: I would say this: The one element that Danielle McCarthy, our producer who came up with the concept for the movie and was working on it before we got on board, got that we ended up using was the [band’s] producer Jim Dickinson. He helped lay out the thesis of the film. The Memphis mentality, the Memphis approach to making music, he was laying that stuff out when he talked about the ’70s, and working with Alex on the third record, he so succinctly would explain Big Star’s place in the scene. It was really kinda hard when he passed away because I always saw him as a potential narrator. Basically I used a lot from that interview to lay out what Memphis ment to these guys and that second layer of background to the music. We also do have some departures into the Memphis bohemian scene. Some of the books we encountered were all about that. We didn’t know how much the Big Star boys were connected to that scene coming in. I knew about their relationship with William Eggleston through Jim Dickinson, but [I didn’t] know that they were all hanging out at the same bars, that you either lived out in the suburbs or in midtown, and midtown had a distinct flavor, a wild place and more or less the center for these guys, that where these boys were playing their music in the studio late at night.

Filmmaker: Were there aspects of the Memphis scene that you found fascinating but you couldn’t fit into the narrative of Big Star as a band that you couldn’t fit into the narrative of the film.

DeNicola: Oh, of course. We encountered so many stories that I wish we could have explored more, than could have been their own films. The whole idea of the studio culture was really interesting to me. There was this whole Ardent Records scene that was very interesting, but it was just too far afield for us to include.

Mori: It was difficult to avoid all the digressions we could have indulged because so many of them are so interesting.

DeNicola: I was always worrying about how far can I digress before the audience is out completely. Even when I watch the movie now I’m like, “This is sort of a turn, I wonder how this will work,” and everyone’s always like, “I loved that part,” so I’m glad that people can see it and allow it to be more of an essay style. I set out not to make a band bio, but to juxtapose the various elements that are part of the Big Star story and hopefully people will just stay on that vibe.

Mori: We really care about these characters and so much of what we were trying to do was just get people to care about them as much as we do.

DeNicola: We saw these people socially. We were there a long time. We went over to John King’s house and watched a movie. We really became friends with many of these people. I think another hard thing, and we weren’t always successful at it, was to do a little bit of vérité, in order to get out of the talking heads, expand the world a bit. Most vérité is done for hours and hours of following someone around at a time and you just take the best little bit, 1% of all that shooting. We had a different shooting ratio: we’d shoot for three hours and then hope we’d come up with a nice little moment.

Filmmaker: Both Chilton and [Andy] Hummel passed away while you were shooting in 2010. Did that effect the trajectory of the project at all, having two of the surviving members die while you were in production?

DeNicola: We were already talking to Alex before. It brought attention back to Big Star when Alex passed away. I wouldn’t say we capitalized on it, but it was all about being in the right place at the right time. We were there for that tribute concert in Austin. I was running around like crazy for a few days trying to get interviews and cover it the best I could and the eventual concert. Dwight Twilly, who is another power pop luminary, he had a documentary team there and so I was able to get those guys to shoot the concert for me. I thought it would be a major part of the film, but as we cut it became less and less significant. We mounted a Kickstarter campaign right after that and used the material from that shoot. So in a way it helped us.

Mori: It’s pretty hard to imagine what the film would have been like had he let us in a bit more, Alex.

DeNicola: It would have been odd. He wasn’t gonna participate. We talked to him a lot. He’s say, “Well maybe,” then, “Naw, I’m not into that.” He was kind of teasing us. It got to the point where I was like, “Let me come down there and film you playing piano and that will be your contribution to the film.” He’d say, “Maybe, maybe.” Then you’d call him the next day and tell him you were coming and he’d be like, “Yeah that’s fine, you can come down and we can hang out,” but don’t bring a camera or anything.

Mori: Most of the interviews that you see in the film were done after Alex died and it was such an intense loss for a lot of those guys that it definitely changed the tenor of a lot of what we were doing. Everyone had a very troubled relationship with him. He was just that way with people. And yet people still had so much invested in their friendship with him, even as they were trying to make sense of him and his life. That was one of the biggest challenges of the film. Alex is such a huge character and he had a long and interesting life and how to make him a presence without him being willing to be a subject and have a balance between the overarching subject of the band while still doing his life and all of their individual lives justice.

DeNicola: What governed how much we told you about Alex was how much it related back to the larger story of Big Star. The same goes for Chris [Bell]. At one point, we really saw this story being about how these two guys were living in the shadow of this brief period of time when they were making music together. We didn’t want to veer too far from that central idea. We wanted to focus on when they were in the full flower of their power as artists.