Back to selection

Back to selection

Interview with My Prairie Home Director Chelsea McMullan

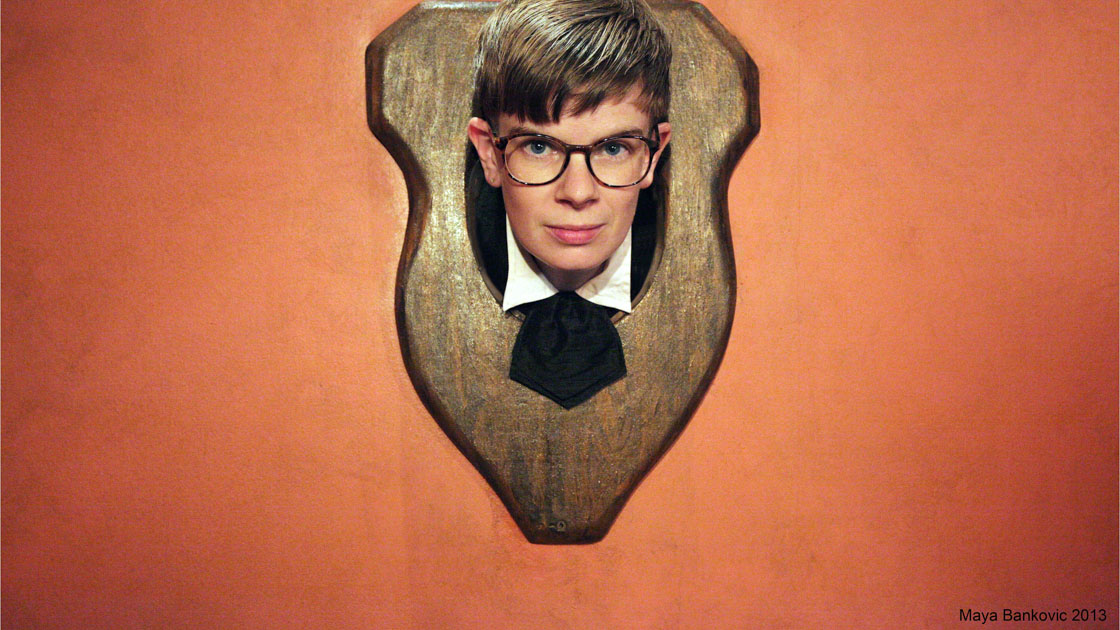

My Prairie Home

My Prairie Home Filmmaker: Why this movie? Why did you decide to do it?

McMullan: Rae Spoon and I have been friends and collaborators for some time. The more they (Spoon prefers the use of the gender-neutral, third-person pronoun) told me about their life and their story, the more interested I was. I just found it fascinating, and I wanted to know more. That started triggering all these questions of my own, about Rae’s specific experience but also broader questions about the context of the world we’re all living in. It was becoming this big knotted ball of curiosity, and I think another part of my brain is always on the lookout for intricate subject matter. That’s the sort of unresolved complexity that can become a very interesting film if you approach it right.

Filmmaker: How much of your crew was female? Was hiring women a consideration for you?

McMullan: All of the key creative on my crew were female except for one. People ask me that question a lot but gender wasn’t a consideration for me. I think experience, personality, creativity and talent weigh much more on my crewing decisions than gender. I’ve been working with many of the same collaborators since I was in university. We’ve all developed a shorthand and I feel like we are trying to build towards something together.

Filmmaker: How did you go about raising funding for it? (I ask this because most female filmmakers says that being female makes it harder to raise funds, so thought your story could be inspiring — I know this topic can be touchy feely, so answer it in the way that you are most comfortable with.)

McMullan: I don’t think my trajectory on this film is applicable to anyone outside of Canada, maybe Holland? I wrote a treatment and pitched my idea to the National Film Board of Canada (NFB) for development funding. The NFB is a documentary production studio while also being a Canadian government agency. I’ve worked with a producer there named Lea Marin for quite some time so I had established a relationship. I pitched to her and we worked on developing the film before it was approved; it’s not a swift process if you are looking to shoot quickly. This film involved these elaborate musical numbers, so I was willing to wait for the budget I needed to pull it off. When I go abroad other filmmakers tell me how utopic it sounds to have an organization like the NFB funding my films. Like anything, it’s not a perfect system. Problems just are going to result from a government agency that’s also a film production and distribution company. But I’m very proud to be a part of an organization with a history stretching back to the earliest days of documentary film. We as Canadians have documented our own history in an incredibly rich and nuanced way, possibly like no other country ever has. In the ’70s, the NFB created Studio D, a women’s production studio aimed at making films by and about women. Quite a lot of important feminist work came out of this studio that I was shown as a young film student. I think Studio D set an important precedent for Canadian women within the documentary genre.

Filmmaker: Do you think a male director might have handled the making of this film differently? How did being a female filmmaker effect how this film got made do you think?

McMullan: I guess it would depend on who the male director was. I do hope that the way I handled the making of the film is uniquely my own, but I don’t think my gender made me more or less empathetic, or sensitive to the subject matter.

Filmmaker: In what ways do you think being a female filmmaker/actress has helped or impeded your trajectory in the film industry?

McMullan: I do inherently believe that it is still more difficult for women in the film industry. Though sometimes I find people are as ageist as they are sexist. There is an old guard of white-haired men watching over the money pot, and cyclically hiring other men. They’re scared now because they know that the industry is changing, becoming more diverse, and there is nothing they can do about it.

From a documentary perspective, as a young female I get a lot of access to places normally forbidden because no one thinks of me as a “professional,” which I take full advantage of. A lot of the time when I’m working with male technicians older than me, they’ll talk to me like I’m in kindergarten. It’s inspired a “No Teacher Voice” policy on my sets. I will also say that there are a lot of established women in the industry who have mentored me and pushed me forward, and I am grateful for that. Mostly though, I just keep my head down and let the work speak for itself.

Filmmaker: Of the big blockbuster movies out there, which do you wish you had directed?

McMullan: Pretty much anything by Yimou Zhang, he’s the master of the blockbuster in my opinion. I love Raise the Red Lantern, Hero and House of Flying Daggers. I don’t have the cultural awareness to be able to direct a film based on Chinese history, but if I were going to make a sweeping historical action film about Canada, there would definitely be homage paid to Zhang.

Filmmaker: What’s next?

McMullan: I’m moving into production of a documentary called Michael Shannon Michael Shannon John with Super Channel in Canada. It is being executive produced by Jennifer Baichwal and Nick de Pencier of Mercury Films (Watermark, Manufactured Landscapes). The documentary is about how 12 years ago a middle-aged, Canadian, ex-police officer named John Hanmer was mysteriously murdered in the Philippines. Surviving him were five children named Michael, Shannon, Michael, Shannon, and John Jr. The duplicated names aren’t a typo. Left behind and scattered across the globe by John’s troubled life and tragic death, his children have one thing in common – each has been left to resolve their father’s past without him.

I’m also writing a feature-length narrative script called Swan Killer with my partner Doug Nayler. We are calling it a “post cult” movie.

Filmmaker: Considering this will be released at Sundance: A) What do you hope to gain from being at the festival? and B) Who would be your dream person to meet while there?

McMullan: A) As a small hybrid documentary-musical from Canada, this film has been a bit of an underdog from the beginning, but I’m hopeful that it gains momentum and exposure from the festival so that a lot more people are able to, and will, go see it. I think Rae’s story is an important one and I hope that it can inspire the sort of conversations that we should be having around the idea of gender.

B) I know I should say someone in my own industry, but to be honest I think it would be pretty cool to meet Nick Cave. I like his music and his films, I also think he is someone who transcends labels and expectations in a really interesting way. Which is why I think programming music docs about him and Rae together in the same year is an interesting choice.

Filmmaker: What is a question I should have asked but didn’t that you think is relevant to this film?

McMullan: Maybe what I hope viewers take away from My Prairie Home?

My intention for the film was to create a biography of a feeling. I want the audience to really understand in a visceral way what it’s like to be Rae Spoon. Also if it exposes more people to Rae’s music, then that’s great too. I have so much respect for them as an artist. I don’t think there are too many artists out there like Rae, who have total autonomy over their work. They’ve never really played any soulless “industry” games. Instead they just sing out and let the music speak for itself. Finally, my films are not overtly political but I would love if this film starts a conversation about gender. Since meeting Rae, my perspective on gender has totally shifted. It’s liberating when you sort of let the binary fall away and just be. I think we are on the cusp of a gender revolution. Gender-neutral washrooms for all!