Back to selection

Back to selection

Director Phillip Rodriguez and Producer Jennifer Craig-Kobzik on Life, Death and Legend in Ruben Salazar: Man in the Middle

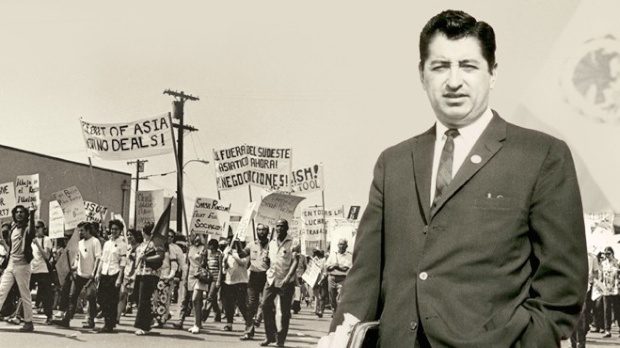

For the generations who have come of age knowing the legend of slain journalist Ruben Salazar, there is as much they don’t know about him. A new documentary, Ruben Salazar: Man in the Middle, takes advantage of police records and decades of hindsight to take Salazar out of myth and give him back his humanity. The film premieres as a Special Presentation of PBS’ VOCES on Tuesday, April 29 at 9:00 PM ET.

Salazar’s contribution to journalism began in the ’50s with his work as a reporter with the border daily El Paso Herald-Post in the city where he had been raised after his family moved to the U.S. from Mexico. He moved on to work as a foreign correspondent in Vietnam and Dominican Republic for The Los Angeles Times at a time when the staff was nearly 100 percent white and male, later becoming the paper’s bureau chief in Mexico City.

After being asked to come back to the States and cover the burgeoning Chicano civil rights movement for the Times, Salazar decided he could focus on the subject more effectively as news director for Los Angeles Spanish-language TV station KMEX. The documentary couches this as a transformation “from a mainstream, establishment reporter to primary chronicler and supporter of the radical Chicano movement of the late 1960s.”

The switch from a major market newspaper to a Latino-oriented television news broadcast also marked a personal shift for Salazar, who for years had eloquently journaled his struggle to be accepted by the Anglo establishment while simultaneously not feeling fully Mexican (his private writings are referenced in the film).

As Chicano rights garnered more support and suspicion as a result of school walk-outs, grape boycotts, and Cesar Chavez’s United Farm Workers march through California, Salazar’s reporting about the movement became more impassioned. He began to worry that he, too, was under as much surveillance by law enforcement as those who were actively leading disruptions to the establishment, especially given his investigative reports shedding light on conspiracies by the LAPD to plant evidence on Chicano suspects.

With the risks in mind, Salazar and a KMEX colleague attended the National Chicano Moratorium March to watch tens of thousands walk the streets in protest of the Vietnam war. Ducking into an East L.A. dive bar after rioting broke out, Salazar was shot in the head by a tear gas projectile fired into the establishment by a Los Angeles County Sheriff’s deputy. Thus, a martyr was made, with Salazar’s story memorialized by everyone from Hunter S. Thompson to Former U.S. Ambassador to the Dominican Republic Raul Yzaguirre over the past 40+ years.

Was it murder? Was it an accident? Who really was Ruben Salazar? And how do you tell the story of a person’s life when they have already been encapsulated in the amber of pop culture mythology? Director/producer Phillip Rodriguez and producer Jennifer Kobzik worked for more than four years — producing another documentary in the time it took to complete this one — to do due diligence to the Salazar family and the work of a man who never intended to be in the spotlight, much less become a patron saint to a cause.

The filmmakers also enlisted the help of the Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund (MALDEF) in filing a lawsuit against the L.A. County Sheriff for not releasing public records related to the investigation of Salazar’s death. That new documentation and dedication to the definitive truth of one man’s life earned the participation of Salazar’s daughter, journalism colleagues, witnesses and, most improbably, the deputy whose shot killed Salazar.

Filmmaker Phillip Rodriguez’s last documentary, Race 2012, used the 2012 presidential election as a lens through which to explore America’s rapidly changing demographics. His previous works include Latinos ’08, which examined the 2008 presidential election and race and Brown is the New Green: George Lopez and the American Dream. Jennifer Craig-Kobzik, who worked with Rodriguez on his last half-dozen projects, also produced. Other credits include Claudio Rocha, cinematography and animation; Michael Zapanta, editing; and Jon Oh, sound design.

Filmmaker: What sparked the idea of doing a documentary on Ruben Salazar? Were you surprised that an in-depth doc about him had not been done before?

Rodriguez: The Salazar story is a staple of the Mexican-American narrative. Virtually every Baby Boom era Mexican-American knows the story, often with a strong opinion about it. And no, I wasn’t surprised. Los Angeles is replete with great stories that have not been recognized. This is particularly true for stories about minority groups. The film and TV business are brokered by folks with very little contact with the honest to goodness Los Angeles. Let’s hope that changes.

Filmmaker: Jennifer, how and when did you get involved in the process?

Kobzik: I’ve produced several documentaries with Phillip and his team in the past and started working on this one during the early research and development stages. From that point I realized the value of this project and knew that I would stay with it until the very end. It’s such a rich, important story, full of discovery and complication in both the actual story of Ruben Salazar and the process of making the film.

Filmmaker: Were Claudio Rocha and Michael Zapanta always attached as DP and editor, respectively? Phillip, how did your previous collaborations with them contribute to the shaping of this film? Was there anything that the three of you wanted to do differently for this particular doc versus your previous projects?

Rodriguez: I met both Rocha and Zapanta while in film school, a long time ago. (Think 16mm upright Moviolas.) Rocha has collaborated with me on nearly all my projects. He’s a really special talent and person and brings so much taste, beauty and thoughtfulness to these films. We brought Zapanta as a replacement for an editor of a previous film. That collaboration was so successful that we knew that we wanted him for Ruben. As far as doing things differently, much of what we’ve done is idea-driven, trying to illustrate abstract ideas with pictures. That’s a really hard thing to do. In this film, we had the advantage of a built-in storyline — a person’s life. I think that freed us up to concentrate on constructing a more dramatic narrative while still getting some good ideas in.

Filmmaker: Was fundraising difficult for this project? What did the majority of your funding go towards?

Rodriguez: It’s always difficult, but this one was especially tough. Our primary funder was the Corp for Public Broadcasting Diversity and Innovation Fund. Additional funding came from Latino Public Broadcasting, Cal Humanities and the California Community Foundation. We appreciate them all, but during this project we learned more funding is needed in the future to sustain the work it takes to make these films happen.

Filmmaker: To your knowledge, was this the first time the Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund (MALDEF) had become involved in a legal case involving a film? Was it difficult to convince them to come on board to fight for the release of files about Salazar’s death?

Rodriguez: I don’t know about MALDEF’S experience with filmmakers, but they were great with us. It wasn’t difficult at all to convince them. Tom Saenz, a brilliant guy and one of my new heroes, is Mexican-American. He knew the story and he understood that the mystery surrounding Ruben’s death mattered to a lot of people. He also knew that the LASD was withholding access to public records that we had a right to see.

Filmmaker: What kind of risks does a filmmaker undertake when they seek to portray as much of the truth as possible about a figure that has become almost mythical via the mysterious circumstances of his death, as Salazar had for the Latino and Chicano activist communities? How did you balance what Salazar had come to mean over the past four decades with what you discovered about his life and death through your research?

Rodriguez: That’s the best question anyone has asked me yet about this film. I was well-aware of the mythology that shrouded the Salazar story and I never felt very satisfied with it. Like a lot of Civil Rights era stories, Salazar’s had been embalmed by the politics of victimhood. So this capable, urbane, courageous Silent Generation guy becomes a stand-in for the ambitions, resentments and frustration of the Baby Boom generation. As the son of silent generation Mexican-Americans, who like Salazar were educated and pretty interesting people, I sensed that Salazar’s identity had been shortchanged. I believed him to be much more useful and more politically contemporary than the Chicano generation had allowed. We set him free.

Filmmaker: What responsibility did you feel as a documentarian (and, in a way, a journalist in the same vein as Salazar) with the new files, photos and other information that came into your hands? Did any discoveries among those files change your vision for the film as it went along? To quote the documentary, how does one who feels passionately about their subject matter walk the tight rope between being a “pimp for the revolution” and a “shill for the establishment”?

Rodriguez: I felt a lot of responsibility. I knew that this story was steeped in symbolism and memory for some people, and I wanted to respect that. I also knew that the vast majority of people who will see this film, never heard of Salazar and weren’t particularly inclined to care, unless we offered up a very good film which fortunately we have. Our credo while making this film was much like Ruben’s—stick to the facts. That’s what we tried to do.

Filmmaker: In the same respect, was it difficult to recruit the participation and cooperation of Salazar’s family? What was that process like?

Rodriguez: If someone came to me intending to make a film about my father, I’d be wary and they were. But at the same time, they had waited a long time for their father’s story to be told honorably and well. They were very helpful, really terrific.

Filmmaker: Who is your ideal audience for this film? Who is it your priority to reach with it?

Rodriguez: All we can do is make the best film we can. The film is a story about a regular guy who, motivated by principle, challenges an abusive authority at great risk to himself – it’s a classic American story. We want it to be seen and enjoyed by as many folks as possible.

Twitter: @RubenSalazarPBS

Facebook.